In his Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry, William Butler Yeats noted that:

“The bodies of saints are fastidious things. At a place called Four-mile-Water, in Wexford, there is an old graveyard full of saints. Once it was on the other side of the river, but they buried a rogue there, and the whole graveyard moved across in the night, leaving the rogue-corpse in solitude. It would have been easier to move merely the rogue-corpse, but they were saints, and had to do things in style.”

In Acadiana, in south Louisiana, down among the cane fields in Saint Landry Parish, at the junction of two bayous — Bayou Teche, Bayou Fuselier — in the tiny town of Arnaudville, in a simple, stately mausoleum in Saint Francis Regis Cemetery, rest the mortal remains of by all accounts a good and holy man, and quite possibly a saint: Auguste Pelafigue. Nonco, as he was and is still known — a nickname, ‘Uncle O’ in Cajun French.

His grand-nephew, Mr. Willie Wyble, in charge of maintenance at Saint Francis Regis Catholic Church across the street, told me he has no doubt Nonco is a saint, and that one day the Church will declare him such. Why? Because he saw Nonco with his own eyes — even though Mr. Willie admitted, with a smile, he’s not much of a saint himself, and sometimes wonders how much time he’d get in Purgatory for strangling someone.

Mr. Willie’s grandmother was Nonco’s eldest sister, and in 1889 when she was eight and Nonco only a year old their family emigrated to Arnaudville from Beaucens in distant France. Nonco trained as a teacher, and for many years followed this vocation in the public and parochial schools of the area. He was known as a gifted catechist, for organizing pageants and processions led by the children, and when I asked Mr. Willie if he ever took part in any of the celebrations he rolled his eyes — oh yes, of course — and remembered for me the tongue and groove floor of the stage in the church auditorium, where Nonco would chalk arrows: one color for this way, another color coming back, to get the children to follow his directions.

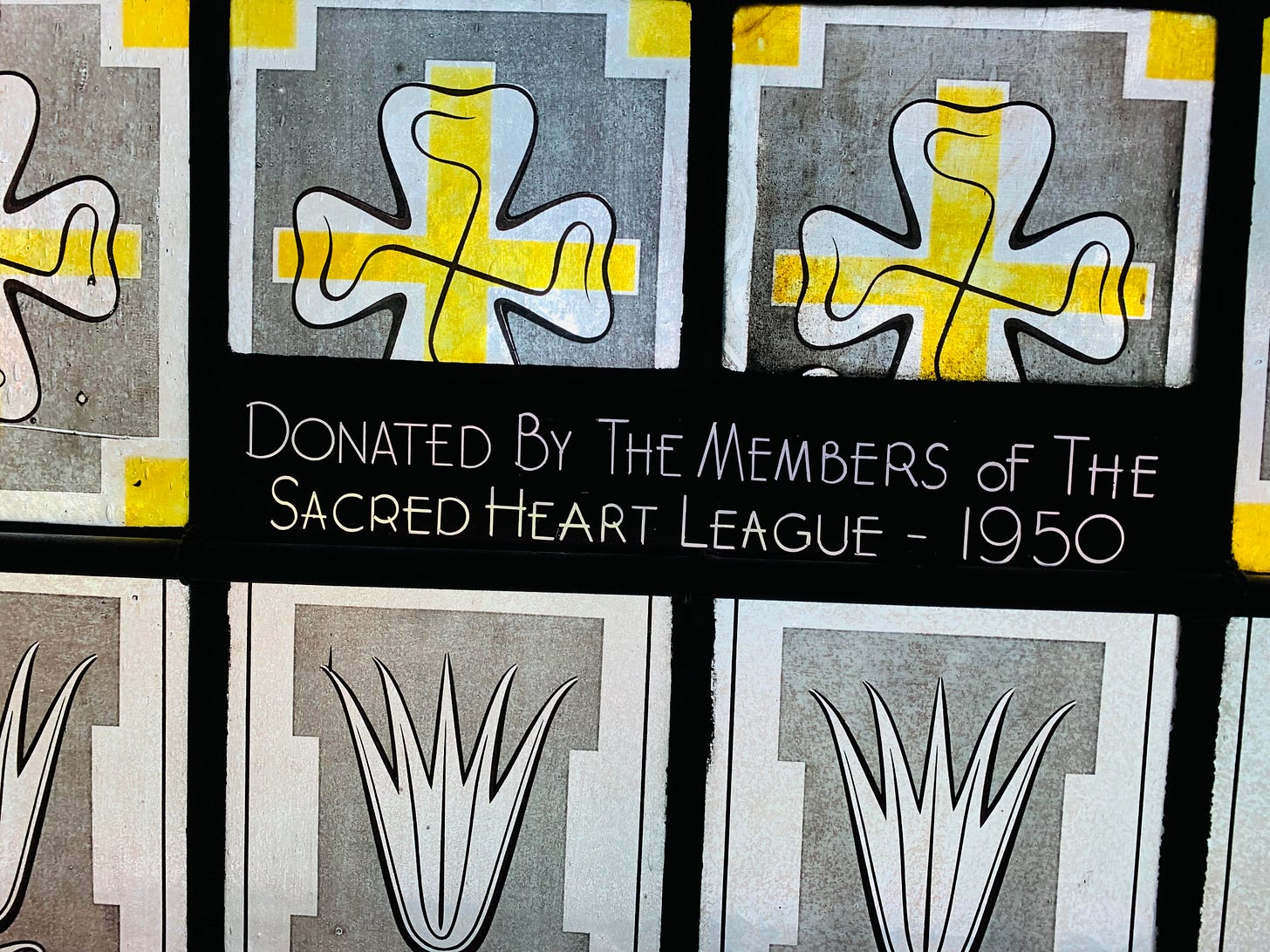

Nonco was known as well for an intense and single-minded devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus. Never one to watch the game on Sunday or head to the barbeque, he would instead set out on foot (with an umbrella to shield him from the sun or rain, and with a small dog perched on his arm) to promote the League of the Sacred Heart, cutting through the cane fields to visit those who needed visiting, to pray with them, and to leave with them the leaflets of the League. When he visited he would sit always on the porch, would go inside only in the worst of weather, and if he did would never sit in a rocker or on a sofa, but only sit on the sofa’s arm. Mr. Willie thought Nonco did this to keep from distraction, especially television.

And on his visits Nonco would always walk, even in bad weather, even as old age took its inevitable toll — he saw it as a penance, and offered it for the souls of the suffering dead.

He was a humble man, living a life of charity and holy poverty. Whenever anyone began extolling his virtues Nonco would start ‘pigeoning,’ as Mr. Willie called it —making a trilling, cooing sound in the back of his throat, shaking his head, start walking away, as if to say: “No, no, not me. Jesus.” He raised fowl, and used the money to help pay for the dues and leaflets of the League for those who couldn’t afford the dollar-fifty. In his small cabin was an every-growing box of uncashed checks, given over the years for his many good works as a teacher, as a catechist, as a man of God — and when asked what these were for, Nonco would say only: “Don’t worry about it.” Mr. Willie regrets, when Nonco died, not being able to add up all that money, to see what Nonco didn’t take.

In 1953, the pastor of Saint Francis Regis was able to request for Nonco Pontifical Honors, and subsequently a Papal Award Diploma and Medal were issued to him by the Bishop of Lafayette. The pastor, in justifying the distinction, had written:

“Mr. Pelafigue has organized the League of the Sacred Heart with some 1200 members and 101 promoters. He goes out on foot to visit the fallen away, invites them to [the] prayer of the league. He teaches in the Catholic school, teaches catechism to the public school children — all out of the love of God — with no pay. He organizes religious programs for the encouragement of the weak, and edification of the strong. He has been in this parish another priest. He is most humble. He attends Holy Mass and receives Holy Communion daily. He assists at all the Masses on Sundays and Holy Days of Obligation. In a word, he is a living example of a real Christian.”

Nonco died on June 6, 1977 — aged 89 — on the Feast of the Sacred Heart.

When I asked Father Travis Abadie, the current pastor of Saint Francis Regis, why in the faith the communion of saints is of such importance, he said:

“Oh, that’s the goal! It’s a direct result of being people of the resurrection. If we really believe in the resurrection, if we really believe that death is defeated, then those who belong to Christ, who have died in Christ and who live in Christ are in many ways more alive than we are. And why are they alive? Why are they in Christ? Well, because they’re a part of the communion of Christ. Why is anyone saved? Because we’re a part of this body of Christ which we call the Church. It’s just one-plus-one-equals-two here — we believe in the resurrection, we believe we’re saved by being part of this communion we call Church — so it only makes sense this communion transcend over the valley of death, as it were.”

He continued:

“The saints give us another incarnation of the Gospel for the time in which they lived — we need those examples — it’s not just nice to see, they’re a necessary part of our education. And then we need to live this communion, this real communion that transcends death, that gives witness to what the final goal is. There’s a reason why the communion of saints is one of the twelve articles of faith that someone has to believe in to be saved, that you explicitly have to believe. It’s not an accident.”

When I asked Father Abadie how Nonco himself might contribute, specifically, to this necessary education, to the edification of the faithful in the wider world outside Arnaudville, he pointed out that the Diocese of Lafayette was ground zero for the sexual abuse crisis in the American Church, with the revelations surrounding Father Gilbert Gauthe is the early 1980s, the first American priest indicted for his abuse of children. In the wake of the crisis, the necessary efforts of the Church to protect young people can often have the unintended effect of establishing an unhealthy distance between adults and children, based on fear, and so adversely impacting the formation of the latter’s faith.

“There needs to be a way,” Father Abadie counseled, “to very prudently, very chastely, but very lovingly, very gently serve our youth. Nonco lived that… this is one thing [his students] constantly gave witness to. He didn’t play favorites. He was never manipulative. Yet children were attracted to him. There was just something authentic about him, something that was very open to the spirit of a child — without breaking any bounds of propriety, he had very effective ministry to kids. I think that’s an important witness we need today.”

The impact of this witness carries through to the present, for it’s Nonco’s many grand-nephews, grand-nieces and former students who have led the push for his canonization. The Nonco Foundation, a predominantly lay organization, laid the groundwork for his cause, advocating tirelessly for Nonco’s heroic virtue and sanctity of life, even drawing the attention of a postulator in Rome, all of this effort leading ultimately to the Bishop of Lafayette formally declaring Nonco’s cause.

Father Abadie also pointed out, in considering Nonco’s special graces, that Nonco died at an advanced age in a nursing home. “I don’t know of too many saints who’ve been canonized,” he said, “who died in a nursing home. And yet I tell you that population is one of the most overlooked… and there are saints there. So Nonco can give us a reminder of that — and the witness, the dignity of the older person.”

Finally, Father Abadie reminded me that unlike many other saints whose holiness flourished within a religious order or religious movement of the Church, Nonco’s holiness was lived entirely within the life of a parish, in collaboration with his pastor, working as a catechist, within the bounds of humble Arnaudville, Louisiana.

I’ve visited Arnaudville twice now, once with my family and once alone. It’s the sort of place where if you’re out on the street someone driving by will stop to introduce themselves and welcome you to town. My wife and I make a point of taking our children to such places — to the birthplace of Saint Kateri in New York State; the shrines of Saint Elizabeth Ann Seton in Maryland, or Saint Mother Theodore Guerin in Indiana; to the grave of Blessed Stanley Rother, the martyr, here in Oklahoma. We want the children to know, simply, what’s expected of them, and teach them possibly the greatest lesson for any American child in this our troubled twenty-first century — that there are many highways and byways to wander along in this great land, to destinations both good and bad… but if they travel always as pilgrims, they’ll surely discover a shrine.

In the mausoleum where Nonco’s remains are interred, my children left wildflowers. One of my daughters left her favorite charm bracelet. My wife left a lock of her hair. We knelt together and prayed for Nonco’s intercession. It was a beautiful day, and Father Abadie brought us a stack of literature associated with Nonco’s cause.

When I returned to the cemetery some years later I was alone. As I walked the grounds, an old man in shorts and suspenders, in his short sleeves, rode back and forth along an adjacent road on his bicycle. In the distance, in the west, rain fell in a silent column from a swollen grey-blue cloud. The cemetery was not like any I am used to — those well-manicured lawns and uniformed rows of the dead one encounters elsewhere. Instead, an old world cemetery, a Louisiana cemetery, a jumble of above-ground tombs of every shape and size, and because this is Acadiana, carved into the stone names that sound like birdsong: Donathilde, Euchariste, Phelonaise, Elodie. On one marker, a simple phrase declaring the hope of us all: ON VA SE VOIR UN JOUR — we’ll meet again one day.

All around me — young and old, rich and poor, men and women alike — the dead. And me among them, alive today, also born to die, but here, still, and wondering about the promise: the promise of resurrection, of this good and holy man who might be at this very moment — just imagine — offering words of praise before the Throne of God.

It often happens, as a cause advances, that the relics of the saint are disinterred and translated elsewhere. It happened here in Oklahoma, with Blessed Stanley Rother taken from his grave in hometown soil, out there in Okarche, on the prairie, and brought to Oklahoma City, first to the cathedral, and then to the shrine that bears his name. At present, there are no similar plans for Nonco, beyond perhaps moving his remains from the mausoleum to his own plot outside, purchased by the Foundation, but still among the dead of that tiny town he loved so much.

How appropriate that he could still journey with them, even in death.

Mr. Willie told me he has no doubt Nonco is a saint, and that one day the Church will declare him such. Why? Because he saw Nonco with his own eyes.

But still we cannot see what lies beyond the veil of death, in what strange country these dead — young and old, rich and poor, saint and sinner alike — reside. What strange country toward which we are all bound. ON VA SE VOIR UN JOUR.

But if we could imagine, for imagination’s sake, Purgatory as something like south Louisiana, only hotter, we might also imagine there those penitent souls of the Church Expectant in their final purification, awaiting their deliverance, their entry into glory.

Imagine then their surprise as a kind old man steps into that fire — from out of the cane fields, as it were — carrying his umbrella, a small dog, and those innumerable leaflets with the promises of the Sacred Heart.

“My friends,” they’ll hear him say, “I bring Good News.”

Brian Kennedy is the founder of Lydwine, as well as the frontman and principal songwriter of the arthouse country band The Cimarron Kings. He lives with his wife and six children in Guthrie, Oklahoma.

NOTES. William Butler Yeats quoted from Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry (The Walter Scott Publishing Co., Ltd., 1888) - Material on Nonco gathered from interviews with Mr. Willie Wyble (October 2021) and Fr. Travis Abadie (October 2023), as well as Auguste “Nonco” Pelafigue: a Documented Biography (Auguste “Nonco” Pelafigue Foundation, 2020).