ONE. At a hotel bar, in Dallas. The televisions on the walls were as long as coffins and twice as wide. On one, a basketball game, its colors unnaturally vivid. On the other, a preview for a special on the Manson murders, followed by an ad for teriyaki salmon and butterfly shrimp, the food grotesquely outsized, bouncing through curls of flame. At another table, sitting alone, a woman chattered loudly on her phone:

“I feel like you might outgrow him — you’re so type-A, so supersmart. I feel you might outgrow him.”

A waiter passed near, and the woman swirled the dregs of her wine.

“May I get another glass?”

I finished my dinner and opened my notebook, started gleaning images from the day’s drive, harvest of a pilgrim road:

Double D Lounge, Thunderbird Liquor, Flashdance Cabaret — dogs on chains huddled in the shade and window units leaking water — Church of Apostolic Lightning, Church of the Brethren, Church of the Word — black widow webs in a junked out car, and someone talking Antichrist on the radio — at the gas station, in the toilet, a delicate sketch of the Sacred Heart across a corner of the ceiling, but on the wall beside the mirror and sink a curved cartoon phallus with a pink swastika tip — the counter attendant had a jasmine lily flower tattooed on his forearm — “She was still learnin’ when she did it. I been lettin’ my daughter practice tattooin’ on me since she was thirteen.”

When I got to the hotel that evening, through the window of my room on the twentieth floor I saw, in gloaming light, as the sun drifted toward the sky’s edge, the sprawl of the city to the west of downtown, the gleam of the Trinity River snaking through its bottomlands. I took a picture through the glass. It seemed much like the landscape from my dream — of the great steel fish and the ruined city on the plain.

I stood at the window for several minutes, watching the sunset, and felt that familiar, peculiar sense of — what should I call it? God’s peace? God’s grace? A sweetness of the heart, an upwelling from within, from that half-hidden place where the senses and mind converge, where the assorted parts of me combine to form the whole.

“A sense of reality,” William James wrote of it, “a feeling of objective presence, a perception of what we may call ‘something there’ more deep and more general than any of the special and particular ‘senses’ by which the current psychology supposes existent realities to be originally revealed.”

It’s not faith, really, though it is perhaps one of faith’s traces. Nor is it constant — only a glimpse of bright sky behind a bank of roiling cloud.

Impossible to pinpoint, and frustrating to describe, the temptation arises to cast it aside, to appease Occam and search for explanations more satisfying to the unquiet, empirical mind: an example of pathological activity in the temporal lobe, or perhaps the synch between the hemispheres of my brain came undone, and what I take to be the touch of God is merely my left brain vaguely aware of its lost and isolated sibling, a voice, like John’s, crying in the wilderness.

And if I cracked apart my skull and dug deep through delicate layers of personality, memory, control, and response I might eventually find a collection of cells grown out of control and pushing, a God from whom I could be delivered by the surgeon’s knife, or death.

Or is that upwelling, that sweetness, instead and simply what has always been preached? The Good God of the Universe, Maker and Destroyer of Worlds, yet who knows me, loves me, and brought me to Dallas, to see my dream again outside my window? And then to see Dealey Plaza, the scene of the crime, in the dead of night, in the dark?

“You can have two types in your life at once,” said the woman with the wine, still on her phone. “My recommendation is to have one type in one place and one in another, so you can go back and forth.”

When the waiter passed by, I ordered another glass of beer. When I spoke to him, I tried to appear as lucid as possible, completely calm and in control, not half-drunk, not frightened. My plan that night was simple, if undeniably stupid. I would drink beer until the bar closed, or close to it, after which I would walk the few short blocks to Dealey Plaza, omphalos of the New Frontier, to see that place apart from the bustle of the day, the tourists and the city traffic, to stand at the corner of Houston and Elm, below the sniper’s nest, in the light of the moon, and then…

“Ghosts are troublesome things in a house or in a family,” wrote Patrick Pearse, the Irish patriot. “There is only one way to appease a ghost. You must do the thing it asks you.”

TWO. I knew a man in Christ who once upon a time, after he ate from a bag of magic mushrooms, saw in the summer moon the face of Christ the King staring down at him, wearing a golden crown and a full brown beard, with silver saucer eyes and white, white teeth, gleaming, a Christ of the blazing Parousia, as though intent on devouring the earth, piece by piece.

At the time this puzzled my friend, bothered him even. No longer a believer, he felt cheated somehow — to take psychedelics and see God was one thing, however clichéd. But to wind up at the mercy of a vision so conventional, so orthodox, was frankly dispiriting. The vision passed quickly, but its memory remained for years, nagging at him, worrying him — until he returned to the Church, at last, to his delight.

There are human footprints on the moon — from twelve American men, sent in pairs — each passage made, of course, in the name of pagan divinity: Apollo, the twin, the archer, the god of music, the god of prophecy and plague. From Delphi, for twelve centuries or more, his priestess in her frenzy counseled the Greeks — Croesus, Lycurgus, even Socrates. From Didyma, in the fourth century, she urged Diocletian to resume the persecution of Christians throughout the Empire — bodies torn limb from limb by clever machines or fed for sport to animals.

His efforts, to say the least, were unsuccessful. Within a decade, Constantine’s vision of the Cross, his apprehension of its power, would fix the course of Christendom for sixteen centuries, until a young nation, still in its salad days — precocious, pragmatic, bloody-minded — a nation seemingly ordained by Providence as heir to all the ancient West’s legacy of both promise and regret, until that nation invaded the heavens atop a Saturn V rocket, in the name of both the old gods and the new.

On Christmas Eve 1968, the crew of the first manned mission to the precincts of the moon, Apollo 8, read aloud from the Book of Genesis to conclude a live television broadcast from the moon’s orbit: In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth. / And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. / And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters.

Hearing this, NASA’s Chief Flight Director Gene Kranz wept openly at Apollo Mission Control. “I cried,” he remembered, “and that’s all there is to it… there are a lot of times in my life when I’ve been brought to tears by just the power, the immensity, the beauty of what we were doing, and this was one of those days.”

Months later, in July 1969, after Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin of Apollo 11 lighted upon the lunar surface at the Sea of Tranquility, Aldrin, a Presbyterian, having carried with him into space a small parcel of bread and wine, took communion in the Lunar Module and read to himself silently a passage from the Gospel of John:

I am the vine and you are the branches. Whoever remains in me, and I in him, will bear much fruit; for you can do nothing without me.

Aldrin had hoped to read the passage aloud, for broadcast, but the Christmas Eve message from Apollo 8 having angered certain atheist gadflies of the time, NASA officials asked Aldrin to keep his commemoration quiet and private, and he obliged. Instead, a small step for a man, a giant leap for mankind, with no mention of God to sully the occasion.

The Apollo 11 astronauts, while on the moon, took a congratulatory call from President Richard M. Nixon, whose predecessor (and nemesis) John F. Kennedy set the entire Apollo program in motion. That Nixon’s administration be the one to realize Kennedy’s goal “of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to Earth” by the end of the decade is no small irony, especially given that while Apollo 11 was in transit to the moon, news broke of the involvement of Senator Edward M. Kennedy, the former President’s youngest brother, in the drowning death of Mary Jo Kopechne at Chappaquiddick, an event which ultimately dashed any hopes of a Kennedy restoration to the Presidency, that family whose fortunes defined the decade — who brought us to the moon, who brought us to and rescued us from the brink of nuclear catastrophe.

“A dark people,” Steinbeck called the Irish, “with a gift for suffering way past their deserving.” For the genuine legacy of America’s first Catholic president was in neither the Apollo program nor the missile crisis, but in an outpouring of significance far beyond the ken of technological excellence or expertise.

Norman Mailer, in hearing the first astonishing eyewitness reports from the moon, maintained it was “as if a man were descending step by step, heartbeat by diminishing heartbeat into the reign of the kingdom of death itself and he was reporting, inch by inch, what his senses disclosed.”

Hyperbole, however poetic — for Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin had indeed gone to the moon, but no farther. Instead, is was John Fitzgerald Kennedy, thirty-fifth President of the United States, poor old glamorous Jack himself, like Orpheus, who’d gone alone into the underworld.

THREE. I remember first reading about it as a boy, in a worn paperback picked up at a library book sale, a gruesome tale of once upon a time — how a young man, Lee Harvey Oswald, after spending a night in the suburbs with his family, a Russian wife and two small daughters, caught a ride into the city with a friend, to his job downtown, on the edge of Dealey Plaza, at the Texas School Book Depository.

Oswald carried with him into the car a bulky package wrapped in brown paper.

“What’s in the bag?” the friend asked.

The answer: “Curtain rods.”

Dallas, Texas — November 22, 1963.

Senator Ralph Yarborough, himself in the President’s motorcade that day, a Friday, later told reporters at Parkland Hospital, where Kennedy was rushed after being shot, “Gentlemen, this has been a deed of horror… Excalibur has sunk beneath the waves…” Such unintended yet unabashed burlesque is commonplace when studying Kennedy’s death. The naked facts, unendurable and irreducible, are clothed as a species of grief in rich garments of metaphor or conspiracy, Shem and Japheth covering their father’s shame. A deed of horror certainly, but that Yarborough should mention in that moment Arthur’s sword, jeweled and gleaming, cleanly uncoupled from the mortal world, and not Arthur himself, pierced “to the tay of the brain,” is telling. No kingly barge appeared in Dallas that day, bound for Avalon, from whence “men say that he shall come again, and he shall win the Holy Cross.”

Instead, a motorcycle officer of the Dallas Police Department, observing the Presidential limousine after its arrival at Parkland, noted “part of [Kennedy’s] skull was laying on the floorboard. Blood and brain material was splattered all over as if a ripe watermelon had been dropped.”

“I didn’t see anything isolated when the President was hit,” one eyewitness in Dealey Plaza recounted. “There was just an explosion. It was almost like a pond hit with water and water flew up.”

The Plaza itself — named for Dallas newspaperman George Bannerman Dealey — is unbearably small, much smaller in person than cameras suggest, as intimate as a boudoir or a grave. The photographs and the films of the killing fail to capture this closeness. Even the shock of Abraham Zapruder’s frame 313 — the President’s blood poured out like dust, his brains like dung, as Zapruder saw through his rangefinder Kennedy’s head “explode like a firecracker” — is deadened by the pseudo-silence of the celluloid veil. To paraphrase Charles Williams, the film like a pocket crucifix preserves pain but somehow lacks obscenity. Recall that as he finished filming that day, Zapruder admits he was screaming.

For Kennedy, it was “the most public private moment of his life,” Jonathan Miller late wrote in The New Yorker. “The publicity was total, and what it did was to conceal, in the very instant that it exposed, the inexorable solitude of dying.”

Miller’s observation is borne out, strangely enough, by the Zapruder film itself. For even in the wake of that final shot to the head — its moist, red blaze — with Kennedy collapsing, falling like cold, driving rain toward an undiscovered country, into the crowded keep of death, even then the eye attends elsewhere. The drama unfolds instead among the living, caught in the spectacle offered by Mrs. Kennedy — Queen Persephone in a bloodied dress — fleeing her seat and crawling aboard the back of the Lincoln, met there by Secret Service agent Clint Hill (code name ‘Dazzle’) come running, too late, from the follow-up car after the second shot. Such is the active conspiracy of the living toward the dead we barely notice, much less regret. Like Hill’s hapless colleagues, who upon seeing their President slain immediately turned their attention toward the motorcade’s fourth car, toward Lyndon Johnson, their new charge — better luck next time, fellas — we the living have journeyed onward, beyond what was for another a final, failed moment.

FOUR. I woke that next morning at the hotel in Dallas chagrined, my plan of the night before — to visit Dealey Plaza in the dark — a failure. I simply lost my nerve. I drank beer until the bar closed, or close to it, but then retired to my room and passed out with the television blaring. A documentary about the war in Vietnam, as I recall.

So, that morning, after a late start I walked to Dealey in the bright sunshine, stood at the corner of Houston and Elm, clambered atop the plinth where Zapruder stood. Taped on the pavement of Elm Street as it sloped down toward the triple underpass was an X marking the spot where Kennedy died, his skull shattered by the final shot. The Plaza already swarmed with tourists. Pilgrims, rather — over a million every year. People milled about, singly or in groups, pointing, whispering, staring. Some even ran out into the street during gaps in the traffic, stood at the X on the pavement, cameras aimed toward the sixth floor of what once was the Texas School Book Depository, at the sniper’s nest kept now as a museum piece, as though they could somehow capture in a picture the fatal bullet hurtling toward them through an elemental aether of remembrance.

President Kennedy wasn’t the only man to die that day — November 22, 1963 — nor even the only public figure. Shortly before the assassination, the writer C.S. Lewis died at his home in Oxford, England, collapsing at the foot of his bed after a lengthy illness. In Los Angeles it was another British writer, Aldous Huxley, dying of laryngeal cancer. That morning he instructed his wife to inject him with one hundred micrograms of LSD, and as he faded toward the pulsing, pleasing light of dissolution later that evening, she read to him aloud from the Bardo Thödol, the Tibetan Book of the Dead:

O son of noble family… now the time has come for you to seek a path…

In the preceding decade Huxley had styled himself an evangelist of both perennial philosophy and psychedelic practice, whilst all the while maintaining, with aplomb, the costume of an English pedant, endlessly clever but seldom wise. In The Doors of Perception he described, under the influence of mescaline, “seeing what Adam had seen on the morning of his creation — the miracle, moment by moment, of naked existence.” Pied Piper of a new Aquarian Age, Huxley wouldn’t live to see the children of the West take up their generation’s struggle, not against fascism or world war or anything so mundane, but against the very mind-forged manacles of the human condition itself, helped along by that precision bombing of consciousness offered by the wonder drugs of the era.

As Tom Wolfe would chronicle so adroitly in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, the counterculture’s plan was simply to “spread out like a wave over the world and end all the bull-shit, drown it in love and awareness, and nothing could stop them.”

To that end came a fete at Golden Gate Park in San Francisco, California on January 14, 1967, styled “A Gathering of the Tribes for a Human Be-In,” the date chosen by an astrologer as dawn of an age when all those now alive on Earth finally outnumbered the dead.

“A new nation has grown inside the robot flesh of the old,” a press release for the happening announced, “Before your eyes a new free vital soul is reconnecting the living centers of the American body.” Advertisements promised a circus-like panoply of celebration, with cymbals, saints, banners, flags, flutes, families, heroes, heads, drums, incense, chimes, children, feathers, candles, animals, lovers, “All S.F. Rock Bands,” even nude dancing, and all for free. Twenty-thousand or more attended. The speakers spoke, the bands played, and a masked parachutist touched down in the midst, to the delight of the crowd.

“Turn on, tune in, and drop out,” counseled Dr. Timothy Leary, late of Harvard University, “Turn on to the scene; tune in to what is happening; and drop out — of high school, college, grad school, junior executive, senior executive — and follow me, the hard way.”

“It may seem, all of it, highly exciting,” CBS News reported later that year, deep in the Summer of Love, “a pleasurable trip into Wonderland — until one begins to wonder about destinations.”

FIVE. The writer Anaïs Nin, who knew Huxley, Leary, and other psychedelic gurus early in the decade, was troubled by their burgeoning impact on American culture.

In her journal, in the summer of 1962, she wrote:

“I realized that the expression ‘blow my mind’ was born of the fact that America had cemented access to imagination and fantasy and that it would take dynamite to remove this block… No one had taught them how to dream, to transcend outer events and read their meaning. They had been deprived of all such spiritual discipline. It was a scientific culture, a technological culture. It was logical that they would believe in drugs, drugs of all kinds: curative, tranquilizing, stimulating and (logically) dream-inducing drugs.”

The true believers of the era saw in frail humanity and our fragile institutions a compromise no longer to be borne, and a special opportunity for America’s celebrated century — which in hindsight seems the sort of can-do optimism that wrought, at the foot of Mount Sinai, the golden calf itself.

Even bearing in mind the 58,000 American dead, the untold number of Vietnamese killed or maimed (including Ngo Dinh Diem, President of South Vietnam, a devout Catholic, murdered in an American-sponsored coup less than three weeks before Kennedy’s assassination), over the longue durée what appreciable difference was there really between the Stacombed rigor of Robert McNamara at the Pentagon — with his charts and briefings and body counts — and the benighted and benumbed denizens of Haight-Ashbury, running enlightenment to ground with blotter tabs of acid?

Each side of the divide in those best and brightest days, despite the rhetoric, “believed in the capacity of rational men to control irrational commitments.” “We thought for a moment,” Kennedy adviser Arthur Schlesinger recalled, wistfully, “that the world was plastic and the future unlimited.” Immanentizing the Eschaton, they used to call it — heaven on earth, and wrought by man. The tribes gathered, yes, but the messiah was us. The rest was fashion, but fruitful. After all, it was not McNamara who gave us the sprawling tent cities of present-day San Francisco and elsewhere, where the new armies of the night — strange anchorites — have fastened, their taste for God’s own flesh forsworn for other, darker sacraments, perched on the precipice of madness.

But for Aldous Huxley on November 22, 1963, all this was immaterial. Instead, it was “his last afternoon as himself,” no longer Adam on the morning of creation, but Adam on his deathbed with Eve beside him, remembering Abel, remembering Cain.

“Aldous had not consciously looked at the fact that he might die until the day he died,” his wife recalled, “Not once consciously did he speak of it.” Not so for President Kennedy, who already before that day received the Last Rites of the Church multiple times, for various accidents and ailments stretching back to childhood. His favorite poem, famously, was Alan Seeger’s “I Have a Rendezvous with Death” and to please him his wife, Jackie, learned to recite it from memory — presumably in that breathy, stylized voice of hers, like a female Capote, just imagine:

But I’ve a rendezvous with Death / At midnight in some flaming town, / When Spring trips north again this year, / And I to my pledged word am true, / I shall not fail that rendezvous.

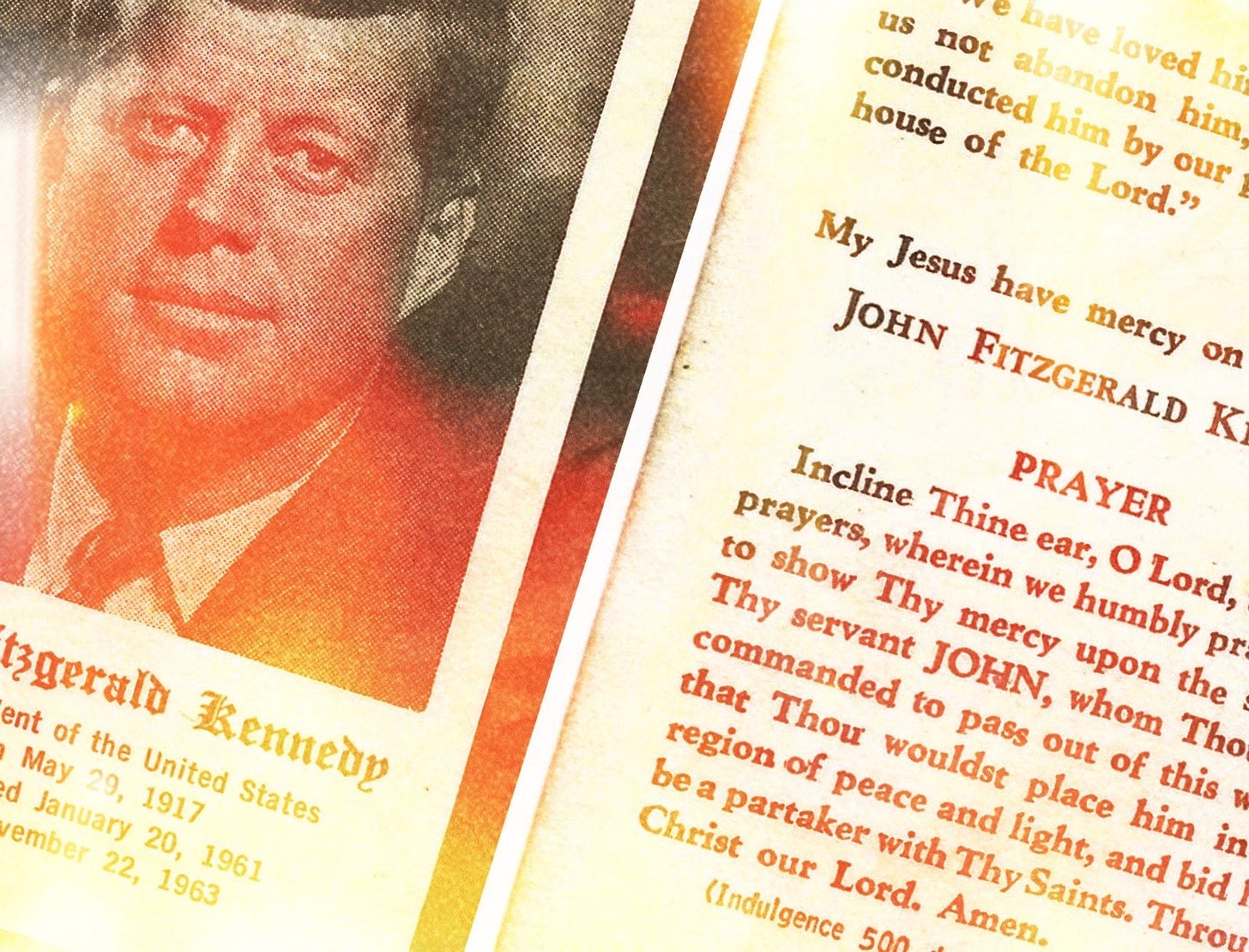

SIX. I once found, in a box of family heirlooms, tucked inside my grandmother’s Saint Joseph Missal from the time, President Kennedy’s funeral prayer card from 1963, his portrait on the front, black-bordered, and on the back first a quote from Saint Ambrose:

We have loved him during life, let us not abandon him, until we have conducted him by our prayers into the house of the Lord.

And then:

My Jesus have mercy on the Soul of John Fitzgerald Kennedy

An indulgence of 500 days granted to all the faithful who pray for the President’s repose.

In January 1964, two weeks before the Beatles first arrived in America, the magazine TV Guide included in its regular weekly issue a special section devoted entirely to the television coverage surrounding the assassination of the President only two months earlier. Introduced by none other than Lyndon Johnson, Kennedy’s successor, it billed itself as “a permanent reminder of [the nation’s] television experience.”

“When Lincoln was assassinated… in 1865,” it declaimed, “Americans had time to assimilate the tragedy. Most people in the big cities knew within 24 hours, but there were some in outlying areas for whom it took days. In the new world of communications there was no time for any such babying of the emotions, no time to collect oneself, no time for anything except to sit transfixed before the set and try to bring into reality this monstrous, unthinkable thing. Because the word was not only instantaneous, but visual.”

Television “had shown that it did indeed deserve to be called… the window of the world. And that the window was capable of encompassing not just life’s trivia, but the deepest of human experience.”

Left unsaid, unargued, unreflected upon was whether television might not be something entirely different from what its boosters proclaimed, that it might instead in every instance exalt the trivial and trivialize the momentous. The murder, for instance, of Lee Harvey Oswald, the President’s alleged assassin, in Dallas on the morning of Sunday, November 24, 1963, broadcast live and watched by nearly half of all American families, many just returned home from their Sunday worship of choice — Oswald himself cast, in this disquieting Camelot, as King Arthur’s final companion, Sir Lucan, “foaming at the mouth, and part of his guts lay at his feet.”

Gripping television, certainly, but whether a medium that brought murder into America’s living rooms might be inimical to the nation’s interests, sinful even, is passed over in silence.

A window on the world, yes, but some windows are not meant for our eyes. To glance through the glass and see two strangers screwing on your front lawn is one thing — to sneak into their backyard for a glimpse into their bedroom is another beast entirely. Whether television has ever proved itself the one or the other is ambiguous at best. That Noah got drunk after piloting the ark to safety on Ararat might be the news, of course, but we still don’t need to see his balls. Immediacy is not a cardinal virtue.

Perhaps that’s too harsh. It’s certainly too harsh. For after Oswald’s murder came the televised splendor of the President’s state funeral, on Monday the 25th of November — the caisson, the caparisoned horse, the widow and her children, the eternal flame. But also a Pontifical Requiem Low Mass at Saint Matthew’s Cathedral in Washington, presided over by what one attendee called “the most grating priestly voice in Christendom,” that of Richard J. Cushing, the Cardinal Archbishop of Boston.

“There is something very admirable,” Aldous Huxley wrote a friend, years earlier, “about the way Catholicism turns what, by itself, is merely a physiological and painfully animal process — dying — into something of cosmic significance, a dignified and tragic act of greatest importance.” Huxley himself was cremated without ceremony on Sunday the 24th, the day of Oswald’s death. Strange that the nation and the world should be initiated via television into the sacred mysteries of the Church in all its Latin pomp and circumstance so shortly before so many of those trappings were swept away by the liturgical reforms of the Second Vatican Council. Indeed, in no small irony, the bishops of the Council voted to accept the schema outlining those sweeping changes on Friday, November 22, 1963 — the day of the President’s death in Dallas.

In the mind and in the heart the images of that November remain — ghosts in our mansion’s corridors, startling us in their persistence. But when you live with ghosts for too long, you grow weary of surprise, grow accustomed to those who drift in and out of shadow — and so often mistake shade for substance, forgetting flesh and blood.

Which is to say, if we remember via television, via images alone, we remember very little. Of Officer J.D. Tippet of the Dallas Police Department, for instance, a father of three, also shot to death by Oswald that Friday — but Tippet wasn’t killed in front of a camera, and so remains an afterthought. Or even Jack Ruby, Oswald’s killer, exemplar of American grotesque, captured in the news footage of course — but how do we square those images with the thought of Ruby sitting in his jail cell, awaiting trial, ashamed of his lisp, and so practicing, for clarity’s sake, for his moment in the spotlight, the Biblical names of Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego… Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego… Shadrach, Meshach, and…

A multitude of detail, coalescing toward plenitude, for which the proliferation of man’s images can never account, however long we “sit transfixed before the set” and summon before us every “monstrous, unthinkable thing.”

SEVEN. Thomas Mann, in The Magic Mountain, wrote of certain difficult and unpredictable elements at work in our reckoning of time, that certain stories “having taken place before a certain turning point, on the far side of a rift… cut deeply throughout our lives and consciousness” might actually be older than “orbits around the sun” could account for. For Mann’s generation, that rift, that turning point, was the First World War, “with whose beginning,” he noted, “so many things began whose beginning, it seems, have not yet ceased.”

For Americans in the latter half of the twentieth century and even into the twenty-first, that turning point is instead and undoubtedly Dallas in November 1963, with what another writer, himself a countryman, called “the seven seconds that broke the back of the American century.” There is in our reckoning of that calamity a basic and understandable before and after — but with the continuity between the two garbled, as though the white noise of the President’s murder interrupted some necessary and unrepeatable broadcast communique from our ancestors, warning of the family method in how to think, how to feel, how to live.

In 1950, only nine percent of American households had a television. In 1963, over ninety. In 1969, over 600 million people worldwide watched Armstrong and Aldrin of Apollo 11 land on the moon. In 1972, only a little over three years later, during the mission of Apollo 17, to this date mankind’s last visit to the moon, the New York Times, in a back page story titled “Apollo 17 Coverage Gets Little Viewer Response,” noted that “while most observers agree on the importance of the moon explorations, for science and for history, the fact is that pictures, no matter how incredibly good their technical quality, of barren moonscapes and floating astronauts become ordinary and even tedious rather quickly.”

So much for Mailer’s thrill of “descending step by step… into the reign of the kingdom of death.” America’s attention had drifted elsewhere — perhaps realizing, if only instinctively, that in that dream kingdom comes a chill from which no spacesuit, no garment of skin, can shield us. That work instead is left to the garments of glory, the full armor of God, the Word made Flesh. “I am the vine and you are the branches,” the Lord proclaimed, “I go before you to prepare a place for you.”

But in our childish enthusiasms we ceased to follow, and instead struck out on our own, alone, away from the Word, toward an undiscovered country.

Brian Kennedy is the founder of Lydwine, as well as the frontman and principal songwriter of the arthouse country band The Cimarron Kings. He lives with his wife and six children in Guthrie, Oklahoma.

NOTES. William James quoted from The Varieties of Religious Experience (Longmans, Green & Co., 1902) – Material (and somewhat reductionist) explanations for religious experience are derived from John Horgan’s Rational Mysticism (Houghton Mifflin Company, 2003) - Pádraig Pearse published the essay “Ghosts” on Christmas Day 1915, only months before the 1916 Easter Rising and his subsequent execution by firing squad – Gene Kranz’s memories of the Apollo 8 Christmas Eve broadcast are from the 1999 NOVA special “To the Moon” – Buzz Aldrin’s account of communion on the lunar surface is from the October 1970 issue of Guideposts – Kennedy set the goal of a moon landing before the decade’s end in a speech before Congress on May 25, 1961 – John Steinbeck quoted from East of Eden (The Viking Press, 1952) - Norman Mailer’s account of the Apollo 11 mission, Of a Fire on the Moon, was first serialized in Life magazine in 1969 and 1970, and remains an entertaining read, as only Mailer (referring to himself in the third-person as ‘Aquarius’ throughout) could make an astonishing occasion like the moon landing mostly about him - Many of the details presented here of the Kennedy assassination and its aftermath are borrowed from William Manchester’s The Death of a President (Harper & Row, 1967) as well as No More Silence: An Oral History of the Assassination of President Kennedy by Larry A. Sneed (Three Forks Press, 1998) - The smallness of Dealey Plaza is noted from personal observation, but is also mentioned by Jean Stafford in A Mother in History (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1966), possibly the most disquieting of all books in the literature surrounding the assassination - Arthurian allusions are from the Winchester Manuscript of Malory’s Le Morte Darthur (Oxford, 2008), edited by Helen Cooper - Jonathan Miller’s piece “Views of a Death” appeared in the December 28, 1963 issue of The New Yorker - Quote from The Tibetan Book of the Dead is from Francesca Fremantle and Chögyam Trungpa’s translation (Shambhala, 1975) - Details on the Human Be-In of 1967 are from Jay Stevens’s Storming Heaven: LSD and the American Dream (Grove Press, 1998), as well as Gene Anthony’s The Summer of Love (Celestial Arts, 1980). The latter notes that the astrologer who chose the date for the Human Be-In was, oddly enough, the grandson of Chester A. Arthur, 21st President of the United States - Anaïs Nin wrote of Huxley, et al. in vol. 6 of The Diary of Anaïs Nin (Harvest/HBJ, 1977) covering 1955-1966 - David Halberstam is quoted from The Best and the Brightest (Random House, 1972) and Arthur Schlesinger from A Thousand Days: John F. Kennedy in the White House (Houghton Mifflin, 1965) - Eric Voegelin discussed the folly of immanentizing the eschaton in The New Science of Politics (University of Chicago Press, 1952), but for a deep dive into the bizarre see also The Illuminatus! Trilogy of Robert Shea and Robert Anton Wilson (Dell, 1975) - W.H. Auden quoted from his February 1939 poem “In Memory of W.B. Yeats” - Laura Huxley’s description of her husband’s death is taken from her December 28, 1963 letter to Julian and Juliette Huxley, but also from her memoir This Timeless Moment: A Personal View of Aldous Huxley (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1968) - TV Guide published “America’s Long Vigil – A permanent record of what we watched on television from Nov. 22 to 25, 1963” in Vol. 12, No. 4 | Jan. 25, 1964 | Issue #565 of that magazine - Cardinal Cushing was described as having “the most grating priestly voice in all of Christendom” by none other than McGeorge Bundy, Kennedy’s own National Security Advisor - Aldous Huxley wrote of Catholicism’s funereal alchemy in a May 1927 letter to Mary Hutchinson – Details on the 73rd General Congregation of the Second Vatican Council for November 22, 1963 are from Floyd Anderson’s Council Daybook (National Catholic Welfare Conference, 1965) – Jack Ruby’s efforts at correcting his lisp are described in Jack Ruby: The Man Who Killed the Man Who Killed Kennedy by Garry Wills (yes, it’s that Gary Wills) and Ovid Demaris (New American Library, 1968) – Quote from Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain is from the translation by John E. Woods (Everyman’s Library, 2005) – Don DeLillo quoted from his novel Libra (Viking Press, 1988) – “Apollo 17 Coverage Gets Little Viewer Response” by John J. O’Connor appeared on page 95 of The New York Times, December 1, 1972 – John 14:3, 15:5.