In the October 1925 issue of Vanity Fair, the poet E.E. Cummings, who saw in the American circus a vision of our nation’s democratic ideal, combining excellence and transience in equal measure, offered a vital observation:

“Within ‘the big top,’ as nowhere else on earth, is to be found Actuality. Living players play with living. There are no tears produced by onion-oil and Mr. Nevin's Rosary, no pasteboard hovels and papier-mâché palaces, no ‘cuts,’ ‘retakes,’ or ‘N. G.'s’ — and no curtain-calls after suicide. At positively every performance Death Himself lurks, glides, struts, breathes, is. Lest any agony be missing, a mob of clowns tumbles loudly in and out of that inconceivably sheer fabric of doom, whose beauty seems endangered by the spectator's least heart-beat or whisper…”

Left unspoken is the presence of Death Himself not only during performance, but afterward — and ultimately, always.

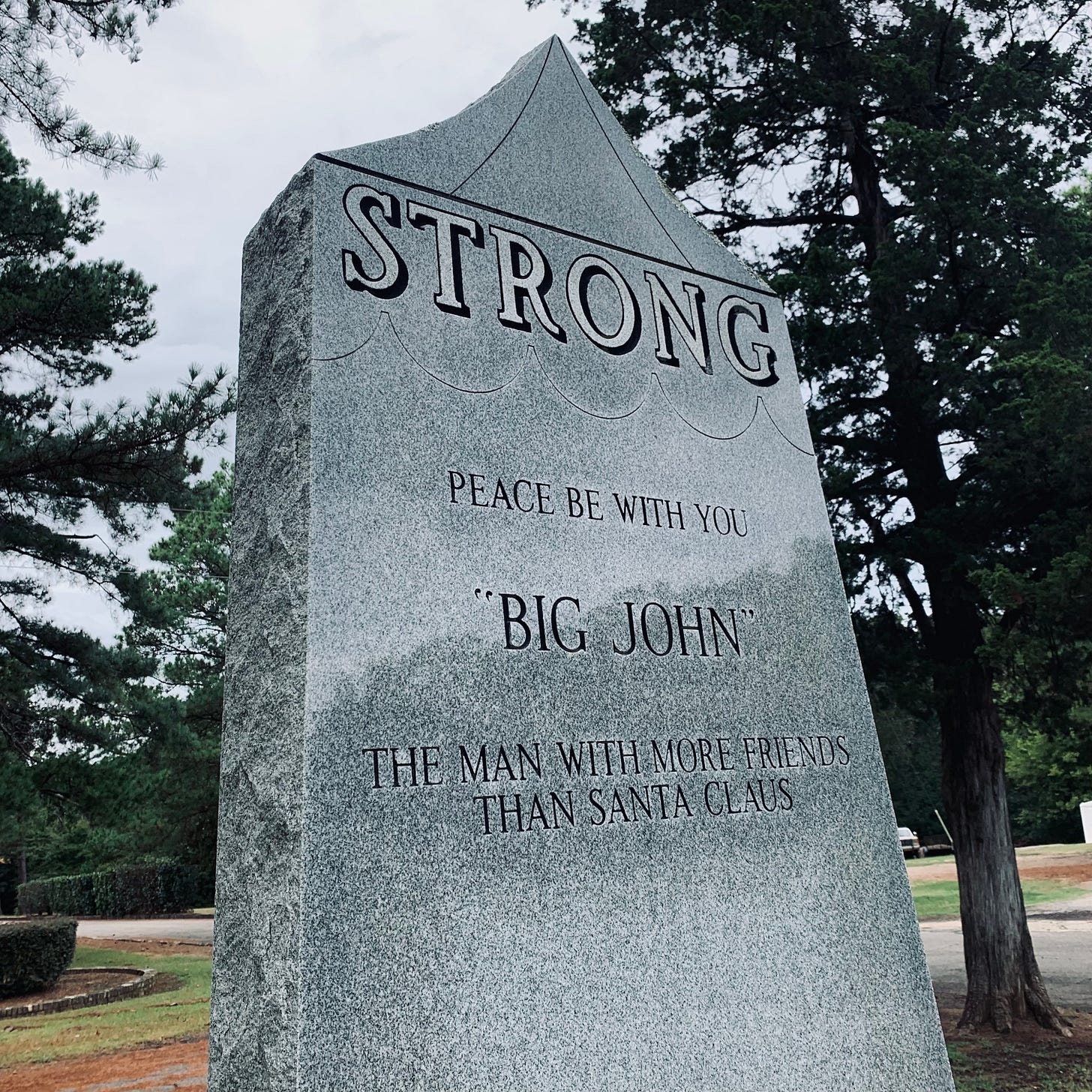

At Mount Olivet Cemetery in Hugo, Oklahoma, a small section of hallowed ground — called Showmen’s Rest — is set aside for the mortal remains of the circus folk who for generations have made tiny Hugo their winter haven. Buried there are impresarios like Jack Moore, who as a young man kept both a lion and a wrestling bear in his mother’s garage in Marshall, Texas; performers like Zefta Loyal, who could dance on pointe on the back of a galloping horse; or Herbert Weber, who as the Great Huberto walked the high wire with baskets on his feet.

“The circus,” wrote E.B. White, “comes as close to being the world in a microcosm as anything I know.” A world in which the sting of death comes quickly for some, yes, but slowly for most.

Popcorn the Clown, interred at Showmen’s Rest, before his death recalled a time when thirty or forty of his fellows might dress together in clown alley before performance, that special tent set aside for the clowns at the insistence of other, nobler performers — who didn’t wish to share a space with the painted fools of the circus ring.

Popcorn recalled as well that number steadily dwindling, year after year, until he alone was left.

Adjacent to the cemetery is Hugo’s elementary school, and so at times the sounds of children, sounds of delight, can still be heard, out there among the graves — a comfort to the departed, and those who stop to mourn.

The poet Robert Lax, who himself travelled for a time with the Cristiani Brothers Circus, penned what seems a fitting epitaph for the dead of Showmen’s Rest, and for those of us yet left behind, who marvel at their witness:

Our dreams have tamed the lions, have made pathways in the jungle, peaceful lakes; they have built new Edens ever sweet and ever changing. By day from town to town we carry Eden in our tents and bring its won- ders to the children who have lost their dream of home.

What a marvel the circus has been in American life. The older generations thought to "run away and join the circus". Even the name circus brings the globe and epochs home under a tent the circle of life, exitus-reditus, and the gamut of creation from the so-called freaks to the great physiques of acrobats and the beasts, and the spectators and clowns of all emotions, together.

e. e. cummings mentions the song, Rosary, by Ethelbert Nevin, a long popular work of piano sheet music, decades later it appeared also in the repertoire of Mahalia Jackson:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GHesvTRAESo