When asked why he chose Saint John of the Cross as his patron, Stanley Booth doesn’t hesitate: “Because I’m a damned good writer!”

In 1984, with the publication of The True Adventures of the Rolling Stones, his long-awaited firsthand account of that band’s 1969 American tour, Booth brought to the canon of American letters the definitive literary treatment of what his late friend and countryman Gram Parsons called ‘Cosmic American Music.’

“No work on the popular arts,” novelist Robert Stone wrote of Booth’s magnum opus, “so faithfully serves its subject while unpretentiously succeeding in being about so much more.”

In the summer of 2019, Lydwine’s own Brian Kennedy traveled to Memphis for a chance to sit at the feet of the master.

But first they had to get in the front door…

After dinner, when we returned to his house — the doors locked, the windows barred, a mid-century brick ranch in a quiet Memphis neighborhood north of Vollintine — the keys Stanley assured me he had proved useless, fitting none of the locks. We tried each of the doors — back, side, and front — one-by-one, then stood together in the Florida room, staring at one another.

“Stanley,” I asked, “what are these keys for?”

“I don’t know,” he said, shaking his head. “What’re we gon’ do? What’re we gon’ do?” I could hear the rising dismay and frustration in his voice, and when I didn’t say anything he answered himself: “We’ll have to break a window.”

“Stanley, wait — let’s figure this out.” I worried for him — an elderly writer, frail, poor, that ever-dwindling envelope of cash in his shirt pocket. “I don’t want you to have to—”

“Wouldn’t be the first time,” he said resignedly, turning away.

We walked back out into the yard. His next door neighbors, an older black couple, were also outside, and arguing loudly, beyond the fence. I tried not to listen.

“Do you have any tools?” I asked.

He eased himself down into a red plastic Adirondack chair, balancing with his cane. “Check the garage.”

But the garage, dark and stifling, held only boxes — of books, magazines, papers, videocassette tapes, and other ephemera — the garage of a writer, no doubt, and completely impractical, or nearly so. In a corner near the door I found an axe. In the back room, a metal curtain rod. I brought it out into the light and flattened an end with the butt of the axe, thinking I could slip the metal between the sash and sill of a window — but still, we needed to get past those bars. I called back outside.

“You don’t have a screwdriver?”

“It’s in the kitchen.”

I walked over to the fence and poked my head through the gate. The neighbors were still arguing, the man standing with a garden hose in his hand, watering flowers, his wife in a chair on the porch, scowling. “I take care of everythin’ f’you!” he yelled at her, stamping his foot. “You sit ‘round here, don’t do nothin’!”

“Excuse me?” I offered politely. They both turned and stared, shocked into silence and a semblance of amity. “Um… I’m next door, trying to help Stanley… he… we… well, we’re locked out. Do you have any tools I could use? I’m gonna try to get in through a window.”

“What you need?” the man asked, incredulous. “Tools?”

I nodded my head. He gave a last angry look at his wife, then turned toward his garage, beckoning for me to follow. From his tool chest I grabbed what I thought I might need, and he followed me back into Stanley’s yard. “I always say, I never have them bars on my windows. Be a death trap, fire come ‘long. How you gon’ get out d’house then?”

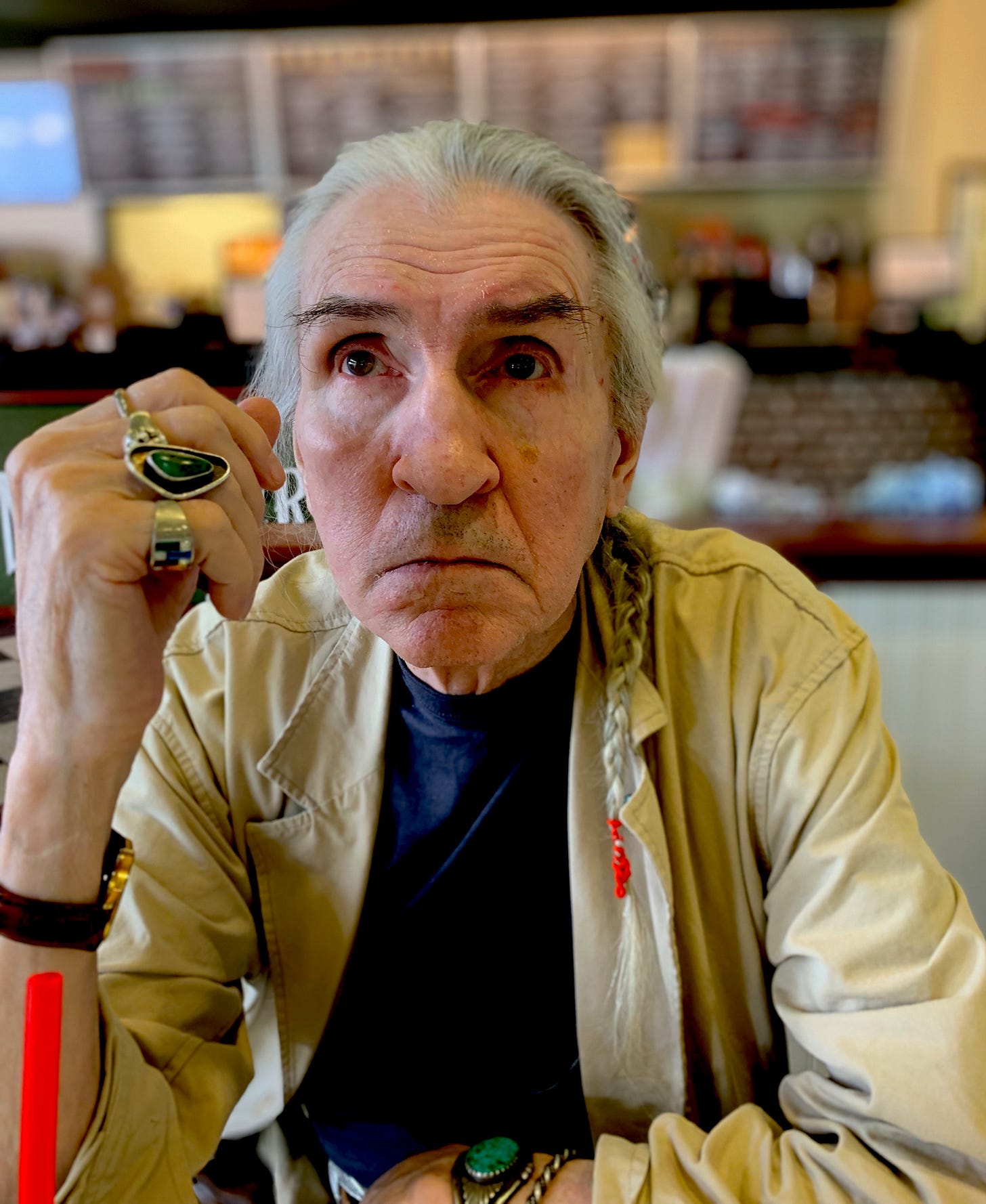

Seeing us, Stanley rose from his chair, slowly. Not for the first time I marveled at how strange and wild he looked, how outside my expectations. I thought of a picture I’d seen of him at a special reception at the Algonquin Hotel in the early ‘70s, having recently been voted, for his piece on Memphis bluesman Furry Lewis, a Playboy Editorial Award. Lean and lithe, he stood with the other honorees, suit and tie and double-grommeted leather belt, looking every bit the swashbuckling young writer, who might discourse awhile on Hemingway or Joyce or Raymond Chandler before running off to score some dope, then screw your girlfriend silly, and never look back.

But that young man was gone — dissipated and disappeared somewhere along the way.

Instead, a small old man, stoop-shouldered, long, white-grey hair tied and braided, trailing down his back over a plaid sports jacket. A fierce face, thin-lipped, frowning, leading with the chin. Rings on nearly every finger, and a silver pectoral cross hanging from a chain around his neck. Dark and dreadful eyes, inscrutable. Resting on the arm of the Adirondack chair, his hat — Italian-made, a boater with a white ribbon, size 7¼.

He looked like an old Indian, but oddly so — “a kind of half-breed maverick Indian,” as he once described Keith Richards, “a make-believe Indian, a Huckleberry Finn.” He called to mind pictures of men shipped east in traveling exhibitions, dressed in European clothes and paraded through St. Louis, Baltimore, Philadelphia, New York, then on to England and the Continent — men smothered and bewildered by the city ways of the wasi’chu, but nonetheless uncowed.

He-Who-Writes-The-Sky. He-Who-Weeps-For-His-Locks.

The Okefenokee Kid, in the flesh.

His neighbor asked about his health, and Stanley told him about his recent stay in a hospital rehab facility, after a bout with pneumonia left him reeling. His time in rehab had been particularly miserable.

“If they didn’t have cans, those people would starve to death. Canned beans, pasta. Corn bread like little stacks of sand, so dry you could barely swallow it.”

To me, smiling, the neighbor said, “He look good. He look wonderful. He doesn’t look like he been sick at all.”

“Don’t encourage me,” Stanley replied.

They kept talking as I made my way around the house, scouting out the likeliest point of entry. I found a bathroom window that looked promising and went to work on the bars with the screwdriver, pulling the screws out one-by-one and shoving them into the front pocket of my jeans. With the bars off I tried to pry the window open with the curtain rod, but the metal proved too flimsy, and couldn’t give me the leverage I needed. The window stayed shut.

By now — this being Memphis, and summertime — I was soaked in sweat, my face and arms covered in grime. Overheated, feeling useless, and unsure of what to do next, I wandered back toward the garage. The neighbor was gone. I looked for Stanley but couldn’t find him. It was on my second pass through the yard I finally noticed him sitting at the top of the steps outside his kitchen door, his head down. He didn’t notice me watching. He just wanted to get inside.

A single, clear thought: He needs your help.

On the heels of that, a memory of something John Paul II was fond of saying: In the designs of Providence, there are no mere coincidences.

At dinner, Stanley and I spoke briefly about Gimme Shelter, the 1970 documentary film from the Maysles Brothers and Charlotte Zwerin following the Rolling Stones on their American tour the previous year, in which Stanley — also on the tour, of course — can be seen several times, most notably while at the Huntington Hotel in San Francisco, strutting around the room with Mick Jagger and Keith Richards, listening to the first rough mix of “Brown Sugar,” recorded in Alabama only days before — that duo’s mad priapic poetry for a brave new world:

Gold Coast slave ship bound for cotton fields / Sold in a market down in New Orleans / Scarred old slaver knows he’s doing all right / Hear him whip the women just around midnight…

“When I see that film now,” Stanley said, “When I see myself in that room, dancing, I think — I put myself there. I wanted to be there, and so I put myself there, I did.” He paused. “I was terrified every single day of that tour.”

Before arriving at Stanley’s house earlier in the day, I stopped at Elmwood Cemetery, resting place of many notable Memphians, including E.H. “Boss” Crump himself, the writer Shelby Foote, and even victims of the calamitous yellow fever epidemics of the late nineteenth century, thousands of them, interred there in a mass grave called No Man’s Land. I came on pilgrimage, to visit the grave of Sister Thea Bowman, a Franciscan Sister of Perpetual Adoration with a cause for canonization out of the Diocese of Jackson, Mississippi. I knew little about here, only that she died young, of cancer, and was buried in Elmwood with her family. Under her name, carved into the headstone, was simply: ‘She Tried.’

On the drive into the cemetery I passed an abandoned industrial warehouse, and had to pull the car over, realizing I’d seen this place before in a dream, years earlier. I dreamt my family and I were part of a massive exodus, a tremendous movement of peoples across the continent. America had finally come undone, and everyone was scattering, trying to make sense of it all and find a safe place to rest. It was dangerous, but exhilarating, and I was so happy to be a part of something wonderful — I knew that within it all was a tremendous opportunity for sanctity.

The warehouse — now before me in Memphis, in the waking world — had been the scene of some encounter at the mid-point of the dream, some moment of opposition in which I felt we’d met our end and couldn’t go on. But the opposition faded — much like the dream — and we continued.

I put myself here.

“Sister Thea, please,” I prayed, standing there outside Stanley’s locked house, “I have to get inside… and without breaking anything. Please, Sister.”

I noticed another window at the back of the house, horizontal, and high up on the wall. There looked to be a small gap between the sash and jamb along one side, and I thought at the very least I might be able to pop the window out of its track without breaking the glass.

I set the Adirondack chair underneath the window and climbed up, balancing on its arms while I worked on the bars with the screwdriver. Finally, with the bars off and on the ground, I jammed the screwdriver into the gap and leaned on it, hard. The window gave a dusty screech and slid open along its track. A blast of cool air washed over me. I hoisted myself up onto the sill and poked my head past the blinds — Stanley’s bedroom. I kicked off my boots and pushed myself forward, falling through onto the bed, dragging the blinds down along with me. After untangling myself, I quickly made my way down the hall and into the kitchen. I opened the door and found Stanley sitting at the top of the steps.

“You did it!” he crowed, “My hero!”

Some minutes later — after closing the bedroom window and putting the blinds back in place, after heading outside to grab my boots and screw the bars back up onto the windows, after walking next door to return the neighbor’s tools — I found Stanley in the living room, sipping a drink and watching television. He turned to me and raised his glass.

“In the nineteen-ought-seventies, you know,” he told me, smiling, “we lived entirely on cocaine, turquoise, and tequila sunrises.”

Brian Kennedy is the founder of Lydwine, as well as the frontman and principal songwriter of the arthouse country band The Cimarron Kings. He lives with his wife and six children in Guthrie, Oklahoma.

NOTES. Robert Stone extolled the virtues of The True Adventures of the Rolling Stones for Salon.com in December 1997 - Lyrics from “Brown Sugar,” by Mick Jagger and Keith Richard. Copyright ©1971 by ABKCO Music, Inc.

I love this story, this homage to one of your heroes. Keep them coming. I'll keep enjoying them, thinking about them long after reading. That's what a good writer does. Keeps you thinking.

Thank you.

You're a wonderful writer. I was totally absorbed in this story, would have loved to keep reading!