Pilgrims Toward a Jubilee

A Partial History of Nelstone's Hawaiians, Forgotten Avatars of Cosmic American Music

August 9, 2025 marks the seventy-third anniversary of the Anthology of American Folk Music, Harry Everett Smith’s unparalleled paean to the pioneer age of American recording.

The following essay, part of an occasional series exploring the ongoing legacy of the Anthology, offers what Lydwine believes to be the first-ever history of Nelstone’s Hawaiians, an Alabama duo whose “Fatal Flower Garden” is the second track on the first side of the Anthology’s first volume, tucked between Dick Justice’s “Henry Lee” and Clarence Ashley’s “House Carpenter.”

“Gaudy woman lures child from playfellows,” wrote Smith in his original liner notes for the track, “stabs him as victim dictates message to parents.” The present account — assembled from census rolls, newspapers, city directories, probate records, death certificates, marriage licenses, chamber of commerce brochures, and fire insurance maps, among other materials — is no less poignant a ballad, nor strange.

ONE. February 1928, in Mobile, Alabama:

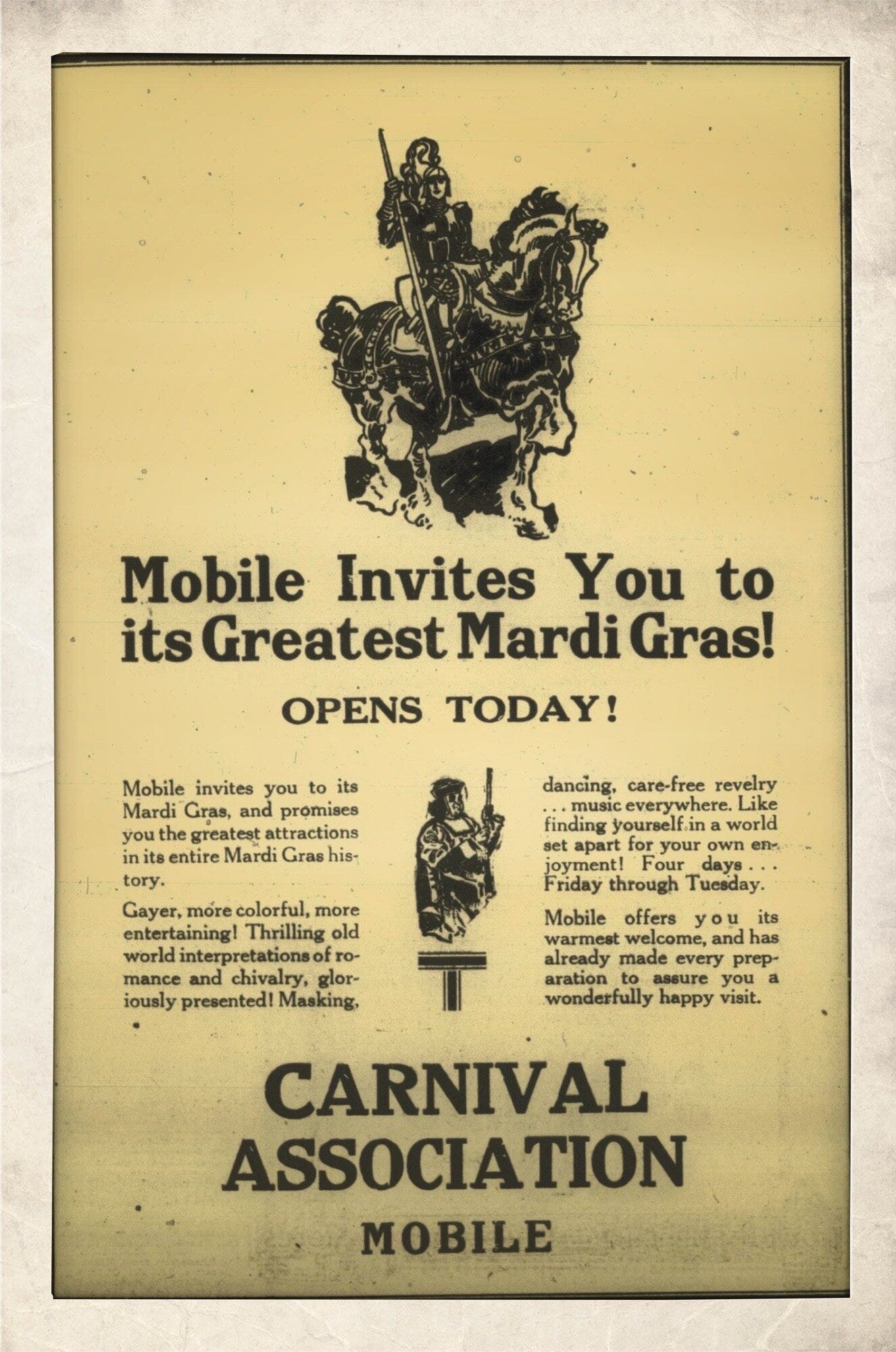

Carnival began that year as was custom with the Friday evening parade of the Krewe of Columbus, celebrating their sixth anniversary, and offering as their theme the spectacle of ‘Saint George and the Dragon’ across seven floats.

“Swishing serpentine, sputtering flares and torches, massed crowds in Bienville Square cheering, sidewalks crowded from curb to building, furnished the background for the colorful procession,” reported the Mobile News-Item, “Beneath a flashing incandescent canopy, sending variegated cones of radiance into the carnival throngs, the parade wound through the business district and out Government Street, its fanciful floats looming in the red glow flung all about them by double files of negroes carrying gaslights and redfire.”

The weekend brought a mask ball on the municipal wharf, boat races in the Mobile River, and a Sunday afternoon of band concerts in Bienville Square. Anticipating a record influx of revelers, the city’s merchants advertised broadly — for carnival candy, carnival costumes, tuxedos, ladies’ handbags and hats, even carnival specials on good used cars. The Jesse French & Sons Piano Company on St. Emanuel Street promised a Mardi Gras sale of phonographs, and six free Columbia, Okeh, or Victor records with any purchase, making special mention of Jimmie Rodgers’ newly recorded “Blue Yodel” (“We Have It. You Should Have It.”) released only a fortnight before, the first of thirteen.

On Monday the year’s King Felix III, ‘Mad Monarch of Mirth’ — a young businessman named Pat Feore — arrived by imperial yacht at the Government Street docks, saluted his assembled subjects with cannon fire, and so unleashed:

“a gargantuan pandemonium. Every vessel in port released the steam from their whistles; the fire sirens screeched insanely; bells and chimes on all the public buildings, and all the factory whistles created a Babel of crazed noise; klaxons, automobile horns, tin horns, clackers, cowbells, noisemakers of every description sent a chaos of happy noise echoing from the buildings.”

Feore (who made a name distributing Seiberling All-Tread Tires, and whose shop was local sponsor of a weekly radio program of that company’s vocal quartet, the Seiberling Singers) paraded to the Athelstan Club on St. Francis Street accompanied by a retinue of fifteen knights, there to receive the keys of the city and greet his queen — Miss Martha Roberts, debutante — with a bouquet of timothy roses. The Infant Mystics paraded that evening, and afterward the king and queen were crowned.

Mardi Gras itself, on Tuesday, saw in quick succession the afternoon parades of the Knights of Revelry, King Felix, and the Comic Cowboys. Public masking was encouraged, and stunt fliers from the Naval Air Station in Pensacola looped and dove overhead. City police broke up a fistfight between two unidentified maskers aboard a Knights of Revelry float. The Sheriff of Baldwin County, on the Eastern Shore, announced the seizure of “2000 pints of red liquor and a quantity of beer” bound for Mobile’s carnival crowds from bootleggers in South Florida.

“Today was a holiday,” proclaimed the News-Item, “Today Pierrot and Pierrette, knights and ladies, pirates and Spanish caballeros, toreadors and colonial maids, Jenny Linds and Ruth Elders, clowns and mummers, mingled in the streets… bands playing, orchestras blaring, laughter and song and feasting were order of the day. For today is Mardi Gras day!”

The close of carnival season 1928 was left, then as now, in time honored fashion, for the parade and ball of the Order of Myths, the city’s oldest mystic society, celebrating their sixty-first year, ‘The Wizard of Oz’ their theme. The Order’s emblem float, however, offered nothing of L. Frank Baum’s vision, but instead a tableau of celebration and anticipation older and far more penetrative — that of Folly chasing Death around the broken pillar of Life, the world for a moment turned upside down.

“Are there other communities existent,” a native son once noted of the scene, “which would take such pains for one night’s pleasure?”

After the crowds dispersed, a gang of prison laborers began the thankless work of cleaning up Bienville Square.

TWO. Mobile lauded itself in those years as “a picture of progress — an old city with new ideas and opportunities,” with over 11,000 telephones in service, 80 miles of paved streets, 60 miles of streetcar lines, 124 churches (64 for whites), seven theatres, sunshine an average of 270 days per year, and “the most conspicuous land-locked harbor from Hampton Roads to the mouth of the Amazon.”

In 1928 Eddie and Marion Teel lived at 416 South Cedar Street, only a mile south of Bienville Square, close to the riverfront and Eddie’s job at the Alabama Drydock and Ship Building Company. The neighborhood was white and working class — boilermakers, carpenters, greengrocers, a miller at Alabama Corn Mills. Marion’s widowed mother lived next door.

The Teels, a young couple with an infant son, enjoyed entertaining and being entertained. A dozen or more guests would gather regularly at the Teel house or elsewhere in the neighborhood to eat and drink, play cards, trade jokes, play games like Bunco or Beanbag or Jack-O-Lantern for prizes, then watch little Patsy Steber, a friend’s daughter, demonstrate (“in her costume of pink spangled tarleton”) the Charleston or the Black Bottom, before spending the balance of the evening dancing themselves to the music of a string band.

Accompaniment for the evening of March 10, 1928 — a Saturday, with showers forecast — was ably offered by two local men, Hubert Nelson and Douglas Touchstone, a guitar duo who for the promotional purposes of the Victor Talking Machine Company would soon be christened Nelstone’s Hawaiians.

Though Douglas Touchstone’s background as a musician is uncertain, by 1928 Hubert Nelson already held an established local reputation as a performer.

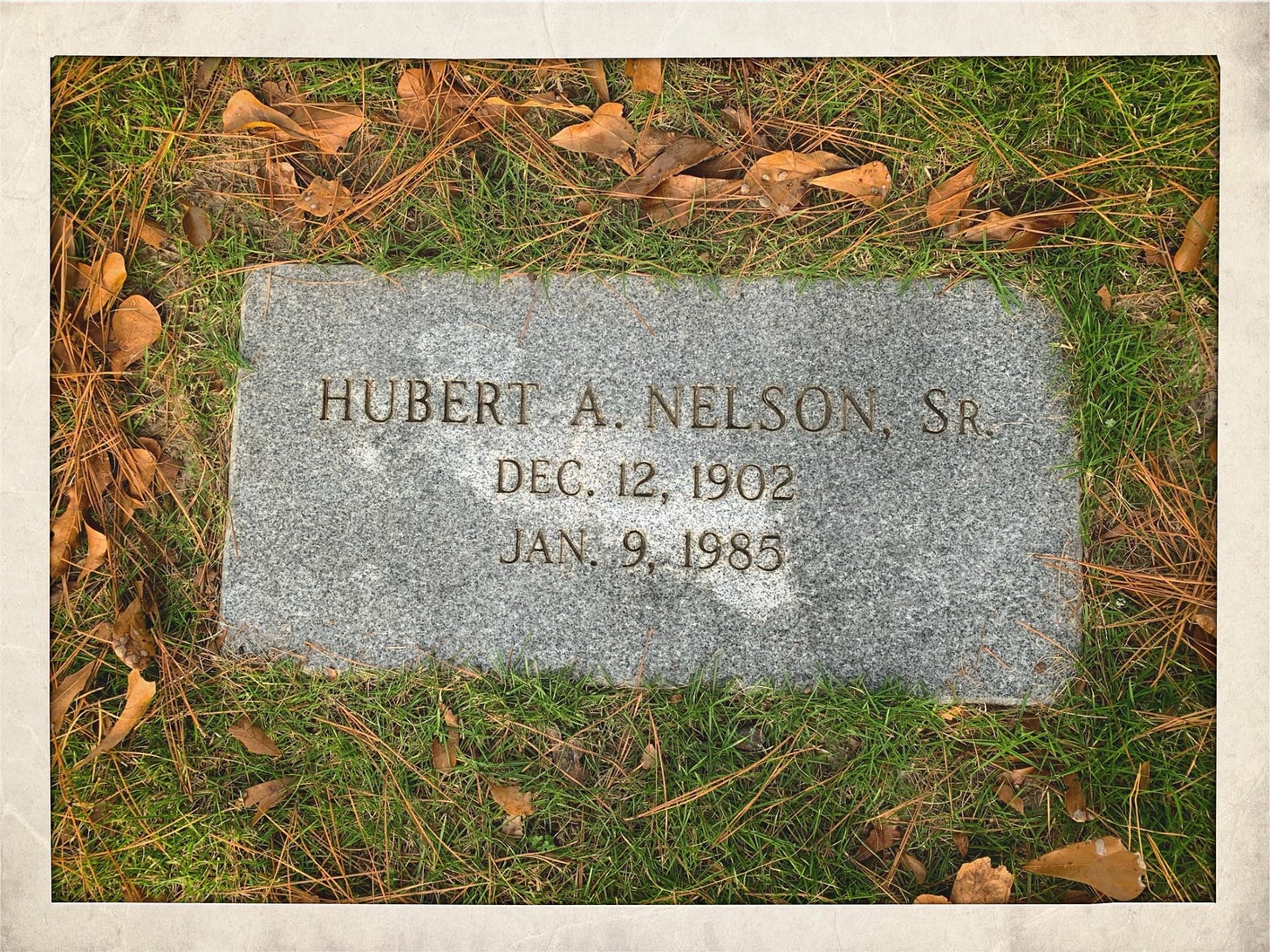

He was born in the Florida Panhandle on December 12, 1902, in a rented house in the tiny village of Bagdad, northeast of Pensacola. His father, Ed Nelson, who worked as a lumber marker for a sawmill, died in March 1910, when the boy was barely seven years old. Sometime thereafter his mother, Hattie — who had already lost three children before the births of Hubert and his older brother, Eben — moved the family west, to Mobile.

By age fifteen Nelson was working in the shipyard, first as a driller helper, then as a driller himself, before finally finding work as a boilermaker for the Gulf, Mobile and Northern Railroad. He married Minnie Rae Lyle in January 1924, when he was 21 and she only 16. Her parents were musicians, and perhaps Hubert and Minnie met at one of the many Saturday night dances held throughout the area — at the Battle House Auditorium, or up in Whistler, or out on Crystal Springs Road.

In the early ‘20s are two newspaper accounts — a christening party and a dance — where Nelson was present and likely provided the music, accompanied by his friend Louis Seymour. But then, in July 1924, in a weekend advertisement for the Bijou Theatre in downtown Mobile, billed alongside a film lesson in Mah Jong, came “Nelson and Seymour, Hawaiian Musical Act,” playing three shows daily.

‘Hawaiian’ pointed to the manner in which Nelson played his guitar — laid flat across his lap, its open-tuned strings fretted with a steel bar or knife, its gliding inflections precursor to the dobro, lap steel and pedal steel techniques since become ubiquitous in American music.

The style, pioneered by native Hawaiian musicians in the late nineteenth century, was immensely popular throughout the United States in the early decades of the twentieth, including south Alabama. In addition to acrobats, illusionists, trained dogs, blackface comedians, and the Dolly Dimple Girls, audiences at Mobile’s vaudeville theatres could turn out to see Jonia and her Hawaiian Orchestra, or Vierra’s Hawaiians on their first southern tour. For the Christmas season, Reiss Mercantile Co. advertised a ‘Jazzitha’, “the new one-string Hawaiian guitar; different from all other instruments; no lesson required; anyone can play it; everybody likes it.” Local record shops stocked titles like “Hawaiian Hotel”, “Hawaiian Smiles”, “Aloha Land”, and “Along the Way to Waikiki.”

“These numbers may be danced to, or just listened to,” read the notices, “with the thrills that come with the ‘Hawaiian Wail’.”

That a local boy should take it upon himself to master a pleasing popular style, however remote its origins, is not surprising — but Nelson was unusually successful.

In April 1927, in the aftermath of the Great Mississippi Flood — a disaster which gave us Kansas Joe and Memphis Minnie’s “When the Levee Breaks” and the “Mississippi Heavy Water Blues” of Barbeque Bob — Mobile organized a Red Cross benefit for the suffering and displaced, which included a parade through the city center, as well as a “Big Nite Club Revue” at the Saenger Theatre. Noted in the show’s promotions as “stringed instrument artists and prominent in the vaudeville world in their line,” Nelson and Seymour offered the crowds “A Night in Hawaii,” and shared the bill with, among others, a dozen blues yodelers and Mobile’s own George Tremer, a blind pianist and noted Gennett recording artist.

Later that year, on the last weekend in October, Nelson and Seymour journeyed to New Orleans with a dancer named Bessie Boyd, the three booked to present “a Hawaiian dancing and musical act” at several venues there. The night they left, before catching the train, Nelson and Seymour entertained a small crowd at the Teel residence on Cedar Street, a gathering of the Good Humor Social Club, the party given a Halloween motif, the house “gay in black and gold streamers and jack o’lanterns.” Joining them that evening with his guitar and harmonica — perhaps for the first time, perhaps not — was Douglas Touchstone.

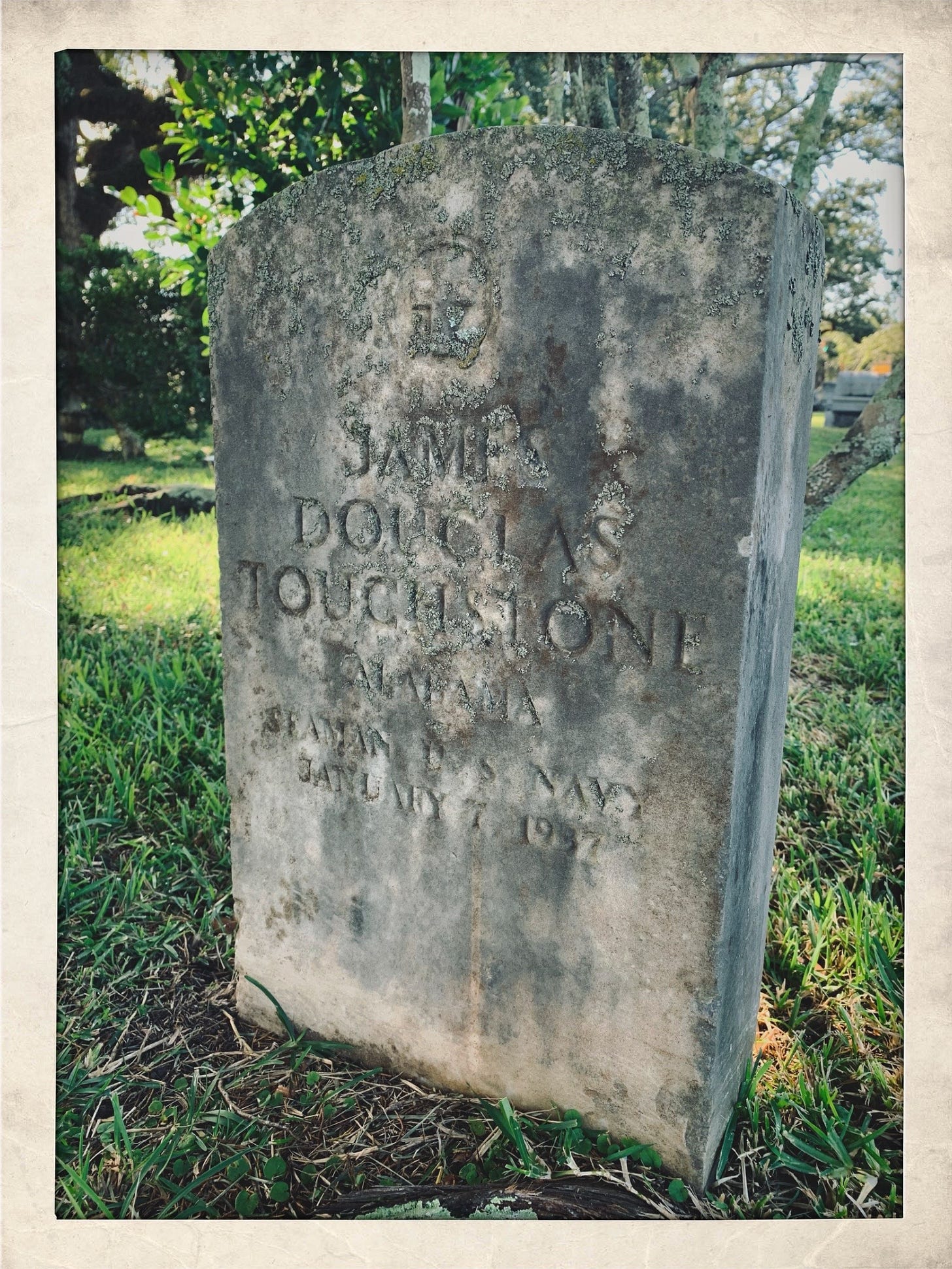

He was born in Columbus, Georgia on February 22, 1897, named James after his father, but called Douglas (his middle name) thereafter to distinguish the two. Shortly after the boy’s birth James Touchstone settled his family in Mobile, working there — first as a brakeman and then as an engine foreman — for the Mobile, Jackson and Kansas City Railroad. In November 1908 James was killed in an accident at the railyard, stumbling beneath a slow moving engine, his skull crushed. His brother, John Touchstone, also a railroad man, negotiated an $800 settlement with the MJ&KC, and was authorized by the probate judge to “invest the money in a home,” for James’s widow, Lizzie, and her three young children, “that they might have some place to shelter them and relieve them from paying rents that they might thereby be enabled to give the whole of their time and labor to making a living for themselves.”

A three-room house was built for them on Bay Avenue, near Bascombe Race Track, on land purchased for $25 from the Sisters of the Good Shepherd. Aside from funeral expenses (paid directly by the railroad, but deducted from the claim) the balance of the money went toward construction materials and household furnishings, as well as clothes for the children and a $16 insurance policy.

As a teenager, Douglas found work as a tinsmith for the Lerio Turpentine Company alongside his older brother, Curtis. When the United States entered the Great War in the spring of 1917, he joined the U.S. Navy, training for six months at Norfolk and Charleston before shipping out for the duration of the war aboard the USS Florida, escorting British convoys in the North Sea. Demobbed, he returned to Mobile, working again at Lerio for a time, but moving eventually to the shipyard as a pipefitter and then as a burner, cutting up scrap metal out on Pinto Island.

He married Minnie Belle Hanson in March 1920, with two children born in quick succession, but by 1925 the couple had separated. Minnie and the children returned to her parents, while Douglas lodged with his older sister, Viola, and her husband, a local cop named Ike Kruse, himself memorable for having failed to prevent the lynching of Richard Robertson in January 1909, having handed over his jailer’s keys to the mob come calling.

The Kruse household at 309 South Bayou Street was only blocks away from the Teels at 316 South Cedar. Louis Seymour lived nearby as well — such proximity perhaps explaining Eddie and Marion’s slate of entertainment. Hubert Nelson lived with own family (by the late ‘20s he and his Minnie also had two young children) much farther away on North Broad Street, in a rented bungalow behind the house of his brother, Eben, the proprietor of a successful Mobile radio shop.

After the trip to New Orleans, Nelson and Seymour seem to have parted ways — there is no further mention to be found of the duo. Seymour and Touchstone, however, performed together at Marion Teel’s 20th birthday party in November 1927.

But then, on that aforementioned Saturday evening at the Teel house in March 1928, after punch and cake and fourteen games of Bunco (at the end of which Mrs. Ed Hamilton won a shoe tree and garter set, and Mr. Ralph Boyes a green and nickel ash tray), “dancing was indulged in, being furnished by Messrs. Tutstone [sic] and Nelson, who rendered several beautiful Hawaiian melodies.”

In 1928 the country was still a decade away from a standard five-day workweek, and that boilermakers, burners, bakers, printers, painters, and their wives should choose, in a rare moment of rest, cards and cake and dancing on a Saturday night, with imagined waves of Waikiki, points toward something subtle, noble and delightful in the human condition — that, with all due respect to the probate judge, no one can rightly live giving “the whole of their time and labor to making a living for themselves.”

“God alone is worthy of supreme seriousness,” Plato counseled, “but man is made God’s plaything, and that is the best part of him. Therefore every man and woman should live life accordingly, and play the noblest games and be of another mind from what they are at present… We ought to live sacrificing, and singing, and dancing, and then a man will be able to propitiate the Gods.”

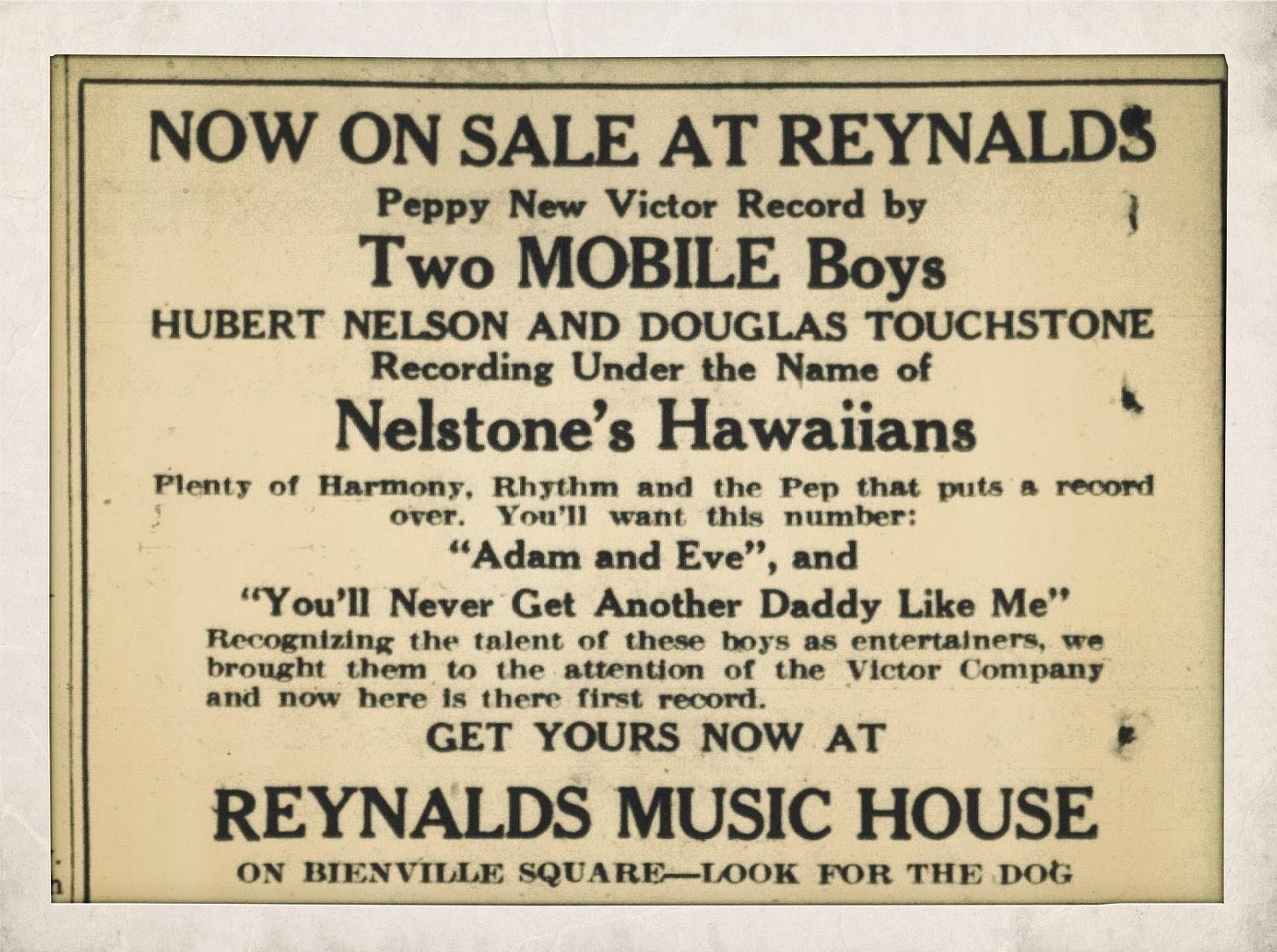

THREE. Reynalds Music House in Mobile counseled any and all in need of the shop’s services (records, Kodaks, Orthophonic Victrolas, Brunswick Panatropes, Radiola Six-Tube Superheterodyne radio sets, including repairs) simply to “Look for the Dog” — a man-sized dog on a man-sized pedestal placed outside their storefront at 167 Dauphin Street, on the south side of Bienville Square, a replica of the mongrel terrier used as trademark for the Victor Talking Machine Company of Camden, New Jersey.

In early 1927, Reynalds approached Victor regarding the commercial potential of the city’s homegrown musical talent. “Knowing that Mobile is rich in the old-time spirituals and melodies of the colored race,” Reynalds proclaimed in a subsequent advertisement, “and that we would be making a distinct contribution to recorded music if we could preserve them on records… the official in charge of race recordings at the Victor laboratories came here as our guest… So impressed was this official that he sent his recording outfit south for the first time in the history of the company.”

Those sessions — held in New Orleans, and featuring two of Mobile’s gospel quartets and a blues singer named Florence White — were supervised by the soon-to-be-legendary Ralph Peer, who later that year would discover and record both Jimmie Rodgers and the Carter Family in Bristol, Tennessee.

It was a similar effort on the part of Reynalds that brought Nelson and Touchstone to their first Victor recording session in the final days of summer 1928, in Memphis. Details are scant for the duo’s work and whereabouts in the first part of that year — in April, a Sunday afternoon house party at a farm on the Eastern Shore, and in August a show for the patients at Mobile’s Cottage Hill Sanitarium, with hula dancing provided by the inimitable Bessie Boyd.

Howsoever they came to the attention of Reynalds and therefore Victor, in the third week of September the two travelled north, most likely by train, to cut four sides at the Memphis Auditorium — on September 21st, a Friday — part of Victor’s months-long residency in the city, which in that week alone would see recordings done by Jimmy Yates’ Boll Weevils, Slim Lamar’s Southerners, Cannon’s Jug Stompers, the Bethel Quartet, and even sermons by Elder Richard Bryant and Reverend Sutton E. Griggs.

“(A musician’s) repertoire would consist of maybe eight or ten or twelve things that they did well, and that was all they knew,” recalled producer Frank Walker, who managed similar sessions for Columbia in the ‘20s, “When you had picked out the three or four best things in their so-called repertoire, you were through with that man as an artist. It was a culling job, taking the best of what they had. You might come out with only two selections, or you might come out with six or eight, but you got everything you thought they were capable of doing well and would be salable, and that was it — you forgot about them, said good-bye, and they went back home. They had made a phonograph record, and that was the next thing to being president of the United States in their mind.”

Of the four songs recorded by Nelson and Touchstone that day, one — an original composition called “Just Lonesome” — was never mastered for release to the public, both takes listed as ‘destroyed’ in the Victor ledgers, quite possibly for some technical imperfection in the recording. “Adam and Eve” was a variation on the chorus of a tongue-in-cheek vaudeville song penned in the teens by the songwriting team of Creamer and Layton, with Nelson alternating between Hawaiian soloing and singing lead, while his partner offered rhythm guitar and a high, quavering vocal harmony:

What did Eve give Adam for Christmas? / That’s something I don’t understand

You never saw a picture of him with an overcoat / and I know he never wore a four-in-hand

He came out early Christmas morning / and on his face he had a pleasant smile

But what did Eve give Adam for Christmas / had been worrying me awhile.

The final two tracks — “You’ll Never Find a Daddy Like Me” and “North Bound Train” — were both sung by Touchstone, the former a lighthearted double-time lament from the point-of-view of a jilted lover, and the latter a version of a common Tin Pan Alley and folk motif, that of “the stern conductor assisting a little boy or girl without fare to get home, to reach a dying parent, or to beg a governor’s pardon for a parent.” Eventually released in May 1929 as the B-side to the “Bloody War” of Jimmy Yates’ Boll Weevils, “North Bound Train” was marketed by Victor as an “Old Time Favorite” — though perhaps for a singer whose own father was killed by a train, the song offered something more than nostalgia, an aural context further complicated by the startling fact that, like the child in the song, Hubert Nelson’s mother-in-law, Mrs. Florence Lyle, had herself once petitioned the Alabama governor for a pardon, in August 1900, after her husband George was sentenced to six months in the Mobile County jail for operating an illegal gaming table.

Their songs sent by Victor to be mastered and manufactured, Nelson and Touchstone returned to Mobile, appearing less than two weeks later at an all-star benefit performance for the survivors of the great Okeechobee Hurricane, that storm having recently devastated portions of south Florida, a disaster recounted by Zora Neale Hurston in her novel Their Eyes Were Watching God, as well as the “Florida Flood Blues” of Ruby Gowdy:

Watch the buildings crumble / crumble like a piece of clay

Shows the gods are angry / got the blues so bad today

The concert raised $1000 for the Red Cross, and the duo — called “Wizards on the Stringed Instruments” — were highlighted in the subsequent notices (alongside blind George Tremer, always a Mobile favorite) as deserving of special mention.

In November the men returned to Cedar Street for Marion Teel’s 21st birthday party, for the obligatory Bunco and also a new game called “seeing America by car,” which garnered Mrs. Frank Stanard “a box of lovely rainbow stationery.” Several records were spun on the Victrola, but “the remainder of the evening was spent in dancing to string music.”

In December, to close out the year, another benefit performance, this time the Kris Kringle Minstrel and Midnight Revue for the Mobile Register Ladies of Charity Christmas Tree Fund, supporting the poor children of Mobile — “Hubert Nelson and ‘Slim’ Touchstone will show what an educated finger can do to a guitar” — the show especially significant as the debut in advertisements of their new stage name, Nelstone’s Hawaiians.

FOUR. “Carnival does not know footlights,” noted the Russian theorist Mikhail Bakhtin, “in the sense that it does not acknowledge any distinction between actors and spectators… Carnival is not a spectacle seen by the people; they live in it, and everyone participates because its very idea embraces all the people. While carnival lasts, there is no other life outside it. During carnival time life is subject only to its laws, that is, the laws of its own freedom. It has a universal spirit; it is a special condition of the entire world, of the world’s revival and renewal, in which all take part. Such is the essence of carnival, vividly felt by all its participants.”

In Mobile — called ‘Mother of Mystics’ — the carnival season for February 1929 saw 1000 additional lights strung throughout Bienville Square, a parachute jump put on by the Southern Aerial Service, and a series of performances by Franz, “the strongest man in the world.” Smilo the dancing clown, who once worked for the Ringling Brothers, made a special appearance, wandering the crowds.

“There were groups, pairs of maskers, and in more remote instances, single persons,” the News-Item crowed, “who have garbed themselves in some eerie manner which gives Mobile the appearance of being the city where people of nightmares and fanciful dreams gather.”

Police reported the seizure of several stills, several dozen barrels of whiskey, and a dozen barrels of mash in assorted raids throughout the city. The Krewe of Columbus and the Infant Mystics paraded, respectively, romances of Japan and Old Egypt, while the Order of Myths offered ‘Music Through the Ages’ — their final float bringing “the history of music to the present age of jazz… formed partly by a giant saxophone of gold… in the foreground a grotesque grand piano with bellying legs, gleaming eyes and grinning teeth provided a dancing place for the ‘spirit of ragtime.’”

On February 12, Mardi Gras proper, a careless bystander tossed a match aboard an advertising float of the Oakdale Ice and Fuel Company, setting it alight and injuring thirteen, including Hubert Nelson, who suffered painful burns. The News-Item followed up later in the month with a report on his recovery. “Local Hawaiian Guitar Player Burned in Float Fire is Much Better,” the brief read, noting that “Nelson, together with his accompanist, J.S. Touchstone [sic], have made a hit with their efforts at bringing forth soothing melodies from the guitar and have made a number of records for the Victor Recording Company.”

Victor released “Adam and Eve” backed with “You’ll Never Find a Daddy Like Me” on January 18, 1929, and shortly thereafter the music of Nelstone’s Hawaiians was available as far from Mobile as Bristol, Tennessee, Holdenville, Oklahoma and Klamath Falls, Oregon.

That month, and again in April, the men offered additional performances at the Cottage Hill Sanitarium. “The routine of a tuberculosis sanitarium is one that very few laymen understand,” a patient explained, “Medical science has decided on the rest cure as a means of curing tuberculosis. Mother Nature and Father Time are the only medicines that defeat the plague… practically all the time is spent abed in a relaxed position.”

The Hawaiians’ periodic efforts at enlivening this convalescent community are perhaps explained by certain circumstances in the personal life of Douglas Touchstone, who that year was embroiled in a legal dispute with his mother-in-law, Mrs. Lillie Hanson, regarding custody of his two children, aged seven and five. The whereabouts of Mrs. Minnie Touchstone, his wife, at that time are unclear, but her death certificate from the summer of 1933, at the age of thirty, indicates ‘tuberculosis of the lung’ as the principal cause of death, and that she herself might have convalesced at Cottage Hill during her five-year illness, and so been visited there by her singing husband, is not beyond the realm of possibility.

April’s show at the sanitarium also marked the reemergence of Louis Seymour, not as a musician but as a member of the duo’s entourage, presumably with no hard feelings at being usurped. With Travis Brassell, a local barber, and Tom Kruse, younger brother of Touchstone’s brother-in-law and a driver for the Oakdale Ice and Fuel Company, who had himself survived the carnival float fire alongside Hubert Nelson, the men travelled en masse to each performance, including a show that month on the Eastern Shore, where — as reported in the Onlooker of Foley, Alabama — “all had an enjoyable time. Anyone who wishes these wonderful Hawaiian players for any kind of entertainment, notify H.A. Nelson of Mobile, Ala., they are always glad to render service to anyone.”

In April came also a banquet performance for the newsboys of Mobile’s Pictorial Review, and a similar show in September for the newsboys of the News-Item and the Register, which included a special radio demonstration by Nelson’s older brother, Eben, proprietor of the Nelson Radio Company, Inc. September saw as well Hubert’s participation in an old-time fiddlers’ contest, a Labor Day tradition, competing against a dozen other men, with judging done by a local police lieutenant and the improbably named Dr. A.N.T. Roach, a retired physician and minor figure in a white slavery scandal that had disturbed Mobile some decades before.

The standard Victor recording contract for the era was for one session per year, with the performers paid $50 per recorded side (over $800 in today’s money, adjusted for inflation) plus any expenses incurred. In addition, the performers were given twenty-five percent of any mechanical royalties derived from the sale of their compositions, which amounted to 1/2¢ of the 2¢ statutory total per copy sold established by the Copyright Act of 1909.

However much Nelson and Touchstone might have earned from royalties in the wake of their Memphis session in unknown, but their records presumably sold quite well — well enough that Victor invited the men via telegram for a follow-up session in Atlanta, Georgia in late November 1929. Held at the Atlanta Woman’s Club, a châteauesque mansion on Peachtree Street with its own auditorium, the Victor docket for that week was exceptional — Jimmie Rodgers and Blind Willie McTell recorded, as well as the Carter Family and the Georgia Yellow Hammers.

Nelstone’s Hawaiians cut four sides on Saturday, November 30th, then rounded out their time in Atlanta with a live nighttime broadcast on radio station WSB, showcasing their new number “Mobile County Blues”, an instrumental featuring Touchstone’s harmonica and a spoken intro wherein the men engaged in a comic dialogue about drinking liquor.

Released in July 1930, it was backed with the song “Just Because”, itself set to become an American standard, recorded by Elvis Presley, Brenda Lee, and Conway Twitty among others — so standard in fact it was later the subject of a lawsuit brought by the Peer International Corporation against two other industry concerns, alleging infringement, but with the defendants arguing “that the music had been in the public domain prior to Touchstone’s and Nelson’s writing, and that the latter had copied and appropriated substantial portions of their version from prior copyrights.”

Ironically, this defense is in keeping with Ralph Peer’s own understanding of the many musicians with whom he worked, and how they wrote their songs — that “these men, being what they were, didn’t get the words from a book or from anybody else; they heard them and then they would forget part of them, and they’d make up their own version. These are all versions.”

Peer’s observation is telling in light of the two other songs recorded by Nelstone’s Hawaiians in their second Victor session — a so-called pathetic ballad called “Village School,” based on a turn-of-the-century composition by William Clay and S.R. Henry, and the beautifully titled but disquieting murder ballad “Fatal Flower Garden.”

A quiet waltz, sung in loose harmony, it tells of a schoolboy tempted and then slaughtered by a “gypsy lady, all dressed in yellow and green,” with the young lad calling in his final moments, almost fatidically, for those left behind:

Oh, take these finger rings off my fingers / Smoke them with your breath

If any of my friends should call for me / Tell ‘em that I’m at rest.

With roots in “Sir Hugh,” an anti-Semitic tale of ritual murder and blood libel reaching back to medieval England, nearly two dozen variants of the song had been anthologized by scholar Francis James Child in the 19th century, and the ballad even mentioned by James Joyce in Ulysses. Surely Nelstone’s Hawaiians most startling recording, it is something like a lullaby, but one that disturbs rather than consoles.

For all human history, the music of the past had never been a burden. All music was, practically speaking, music of the present, passed down and replayed, created or recreated on the spot. But the recording angel — with whom Nelson and Touchstone had their brief and fateful rendezvous — changed the nature of that passage irrevocably. We are left in the wake of such encounters with certain echoes (of uncertain fidelity) backward, where ears were perhaps never meant to linger.

“The music and the context that gave rise to it,” the writer Kurt Gegenhuber noted, “were once in fluent conversation, as if speaking in the exclusive, intimate, cryptophasic language of twins…” Torn from an incarnate context, the joys and frailties of certain music — “Fatal Flower Garden,” for instance — become unmoored, and lend themselves to easy caricature in later ages of peace and stability. It is not as though children in our own time are no longer murdered — it is rather the song’s easy familiarity with death that disconcerts, the violence of its world and of its native listeners unambiguous and directly sensible.

Consider that in January 1930, shortly after the song was recorded, Douglas Touchstone’s sister, Viola, was awakened in the dead of night by a noise outside her house. Upon investigating, her husband, Ike Kruse, spied an unknown man lurking in their yard, and so opened fire on the prowler with his pistol. “A pool of blood on the back porch,” the News-Item reported, “after the man had run, showed the shots… had been effective.”

Consider as well that this was not even Viola’s first encounter with a midnight rambler. In September 1906, when she was but twelve years old, an unknown man forced his way into the Touchstone home one night, with her father away on a railroad run and her mother asleep in the front room. The man attacked Mrs. Touchstone, whose screams brought Viola running. “The little girl grappled with him,” the News-Item recounted breathlessly, “and at one time had him by the hair, and she says from the way it felt, the man was a negro.”

The news account’s insistence on ‘a negro’ throughout, identifiable only by the texture of his hair in the hands of a frightened young girl, suggests something of the full dread and pathos of life in the old South, vicious and bizarre. The man stole three dollars, but also inexplicably in the Touchstone’s kitchen “smeared lard all over his face and hands. He left the house by a rear door, and went into Choctaw swamp. He left grease marks on the edges of the door as he went out.”

Which is to say that for Nelson and Touchstone, their friends and families and neighbors in Mobile, a song about a gypsy woman killing a child was less exotic, less rarefied, than our contemporary circumstances might imply. Perhaps as the peace and stability of our own age begin to collapse, something of the context of the old recordings will being to reemerge — monuments not only to the enduring power and mystery of death, but the possibilities of rest, delight, and even sanctuary.

FIVE. In March 1930, centennial year for carnival in Mobile, a delegation of visiting Canadians played a bagpipe concert in Bienville Square. Smilo the clown returned to dance for the crowds, while a young saxophonist from the University of Alabama band fell four stories from a window of the Battle House Hotel during the ball of the Infant Mystics. The year’s King Felix III, a local attorney named C.C. Inge, radiogramed his subjects from his ship Pontchatrain, before disembarking to meet his queen, Miss Sophia Dunlap:

“Greetings to all my loyal subjects in the realm of mirth and merriment. May a spirit of good-will prevail in my kingdom and bring universal joy to its people.”

The Krewe of Columbus offered that season ‘The Congress of the Planets’, the Knights of Revelry ‘St. Anthony’s Dream’, and the Order of Myths what was described in the press as “a parade of horrors” — bloody pirates, savage Indians, goblins and ghosts — but as always using their emblem float to showcase

“the eternal fight between Death and Folly… round and round the broken column of life, Folly, clad in motley attire, drove with golden bladders the specter, Death. All during Mardi Gras night, according to ancient traditions, Folly is successful in driving away Death, but when Lent begins at midnight, the grim reaper is triumphant.”

A month earlier, on February 7th, Victor released “Village School,” backed by “Fatal Flower Garden.” That same evening at the Battle House Nelstone’s Hawaiians, alongside a number of other local performers, played the inaugural broadcast of WODX, Mobile’s first radio station. Listeners throughout the city (including the guards and inmates at the Mobile County jail) responded with telegrams congratulating this new civic endeavor, with some also requesting particular favorites from the band’s repertoire - standards like “Carolina Moon” and “On the Beach at Waikiki,” and even Ike Kruse himself (listening at home with his family) sending in for “Mobile County Blues.”

But whatever enthusiasm Nelson and Touchstone might have felt regarding their blooming career, the Depression was an inauspicious time for selling records — total US sales for the industry fell by nearly ninety percent between 1929 and 1933. Even the great Jimmie Rodgers, accustomed to selling upwards of 500,000 copies of each new release, saw his numbers collapse to only five or ten thousand sales per record.

What specific impact the Depression had on the Hawaiians is unknown. Victor released “Mobile County Blues” backed by “Just Because” on July 18, 1930. Two days earlier, on Wednesday the 16th, the duo played a double rush dance at Bay View. After this, the trail for their music grows stone cold.

Perhaps the general economic situation did take a toll, or the men had a falling out, but it could be that tastes were changing for their audience, as well.

That same year, a Birmingham radio operator named Frank Romeo complained that:

“Hawaiian music is played too much in this country. I think that type of music should be listened to only when one wants to go to sleep, sitting in a deep armchair with his pipe and book. That type of music comes from a country that is hot and dreamy and lazy. And that’s the way it makes me feel to hear it. I just feel the warm, sultry atmosphere of the little Hawaiian islands when I hear the string music that originated there. Another thing that’s wrong with the Hawaiian music we hear in this country is that it’s really not natural. Much of it is written by Americans and the majority of it is played by people who have never been on the islands… Of course, the music is pretty and I like it, but there are just certain times when I think it ought to be played.”

In 1932, for the first and only time and for reasons unknown, Douglas Touchstone listed his occupation in the Mobile City Directory as ‘musician.’ He died on January 7, 1937, aged 39, from bronchopneumonia, and was laid to rest in Magnolia Cemetery in Mobile. His sister, Viola, petitioned the government for a military headstone. Eventually she and Ike Kruse would be buried right beside him.

Hubert Nelson, in contrast, lived long enough to get divorced, get remarried, and watch his two sons build up their own families — his grandchildren called him ‘Papa’. According to his granddaughter, “Just Because” became a standard in the family, memorized by the children who were often called upon to perform. He died on January 9, 1985, aged 82, from complications related to emphysema and cardiovascular disease. His family still has his guitar.

Postscript. On the Eastern Shore of Mobile Bay, only a short drive from the city, occurs a remarkable and unpredictable natural phenomenon called a ‘jubilee.’ In summertime, usually before sunrise, when a rising tide is joined by an easterly wind, from calm water the shoreline will suddenly be crowded with crustaceans and bottom-feeding fish — blue crabs, shrimps, flounders, worm eels, stingarees — that linger in great numbers for several hours at the shore before heading back, unharmed, into deeper water.

Residents of the area keep a careful eye, and when a jubilee is discovered announce its arrival with carnivalesque enthusiasm, alerting neighbors before heading to the beach with coolers, buckets, and even pick-up trucks, where the Bay’s abundance can be gathered by the armful. While science has some understanding of how a jubilee occurs — oxygen depleted water flooding the bottom of the Bay and forcing the marine life toward the shore, as though ushered by an unseen hand — an individual instance can never be anticipated, its bounty offered seemingly by pure caprice, a gift.

As sign and symbol, in the face of all things human and frail, it stands as one tangible promise from the world that the ancient carnival impulse of at last overcoming Death is something more than wishful thinking, and that the fulness of mortal desire might actually be realized, if only at journey’s end.

Or so it seems, which in itself might just be wishful thinking.

In the meantime — often overwhelmed by Death, perhaps, but still unbowed — Folly continues its whirl around that broken pillar of Life.

Its dance quickens especially, we hope, to the music of a good string band:

When the Lord established the heavens I was there, / when he marked out the vault over the face of the deep;

when he made firm the skies above, / when he fixed fast the foundations of the earth;

when he set for the sea its limit, / so that the waters should not transgress his command;

then was I beside him as his craftsman, / and I was his delight day by day,

playing before him all the while, / playing on the surface of his earth;

and I found delight in the human race…

Brian Kennedy is the founder of Lydwine, as well as the frontman and principal songwriter of the arthouse country band The Cimarron Kings. He lives with his wife and six children in Guthrie, Oklahoma.

NOTES. “Facts are collected indiscriminately by the naïve empiricist,” Evan Eisenberg wrote in The Recording Angel, “who lives in fear of missing the one fact that will give meaning to the rest. His fear is justified; that fact will never be found. Meanwhile, classification gives a semblance of order to things. And meaning is left at the mercy of the last hidden mollusc on the last uncharted reef.”

This piece is subtitled ‘A Partial History of Nelstone’s Hawaiians’ knowing full well that a more robust search of the relevant sources will yield still more facts about the lives of Hubert Nelson and Douglas Touchstone, and the particular genius of their music. Ultimately such a search will only underscore how much we cannot know about the duo — their world is vanished, and we are left only with its traces in the present, which is somehow a source of comfort rather than frustration

As mentioned above, this account was primarily assembled from a variety of public documents, but special mention must be made of the vast resources available to a researcher through the portals of Ancestry.com, Newspapers.com, Newspaperarchive.com, and the digital archives of the Library of Congress.

For carnival in Mobile, see T.C. DeLeon’s Creole Carnivals, 1830-1890, originally published in 1890 but reprinted by Bienville Books of Mobile; for fascinating background on Hawaiian-style guitar playing, see John W. Troutman’s article “Steelin’ the Slide: Hawai’i and the Birth of the Blues Guitar” in the Spring 2013 issue of Southern Culture, as well as his book Kīkā Kila: How the Hawaiian Steel Guitar Changed the Sound of Modern Music (The University of North Carolina Press, 2016); the philosopher Plato is quoted from the seventh book of his Laws, as found in Johan Huizinga’s Man at Play (Roy, 1950), but supplemented by the translation of Benjamin Jowett (Dover, 2013); Frank Walker at Columbia Records is quoted from American Epic: The First Time America Heard Itself, by Bernard MacMahon and Allison McGourty, with Elijah Wald (Atria Books, 2017); background on the folk motif in “Northbound Train” is from Railroad Songs and Ballads: From the Archive of Folk Song, edited by Archie Green (Library of Congress, 1968); Mikhail Bakhtin is quoted from his work Rabelais and His World, translated by Helene Iswolsky (Indiana University Press, 1984); Kurt Gegenhuber’s essay “Smith’s Amnesia Theater: ‘Moonshiner’s Dance in Minnesota’” is a model for writing about the music of that era, and is found in Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music: America Changed Through Music, edited by Ross Hair and Thomas Ruys Smith (Routledge, 2017); for information on Ralph Peer and the record industry of the era, see Ralph Peer and the Making of Popular Music by Barry Mazor (Chicago Review Press, 2014); brief mention of the lawsuit surrounding “Just Because” can be found in the August 14, 1948 issue of The Billboard; information on the jubilees of Mobile Bay taken from “Sporadic Mass Shoreward Migrations of Demersal Fish and Crustaceans in Mobile Bay, Alabama” by Harold Loesch from the April 1960 issue of Ecology, and “Extensive Oxygen Depletion in Mobile Bay, Alabama” by Edwin B. May from the May 1973 issue of Limnology and Oceanography; Scripture quote completing the Postscript is Proverbs 8:27-31, as providentially suggested by the never-failing K.P. Dyer.

Special thanks to Leslye Nelson, Shelly Riklin, Kurt Gegenhuber, the Local History and Genealogy section of the Mobile Public Library, the Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library of the University of South Alabama, and the Discography of American Historical Recordings project at the UC Santa Barbara Library.

This ‘partial history’ is dedicated with gratitude to the Rossi and Dudley families of Mobile, Alabama, who first unveiled for the author the customs of carnival, and all mysteries therein.