…in which we discuss with our chaplain the Sabbath, the Lord’s Day, the destination of our bodies, and the life promised and implied by the Eucharistic offering of the Church.

This exchange has been edited and condensed for content and clarity.

LYDWINE: Guardini has a quote, from Meditations Before Mass: “There exists for God in connection with creation a mystery known as ‘divine repose.’ We cannot understand it — what could it possibly mean, rest for the Omnipotent?” It’s a fascinating question — what does it mean to say God rests?

DYER: He contemplates and loves His creation.

LYDWINE: But aren’t love and contemplation already implied in the narrative? Throughout the first chapter of Genesis, God has moments in which He beholds what He’s done, and announces the goodness of His work. It even seems like those moments of recognition actually spur Him toward greater heights of enthusiasm — that the goodness of earth and sky and sea, for instance, is the very means by which He’s able then to draw forth life in all its forms, as though He’s discovering latent possibilities in His own action. But the seventh day, the Sabbath, is somehow set apart.

DYER: There’s a holiness to rest, and a holiness of special emphasis. Heschel pointed that out, quite strikingly — reminding us that as far as Scripture is concerned the Sabbath “was the first holy object in the history of the world.” It’s not an afterthought, it’s of primary significance. And it’s interesting in one sense because, strictly speaking, saying that God rests I think is something more for us than perhaps it is for God. Just as the work of the sixth day calls us to imitate Him, in the Sabbath, in the rest of God, there’s an imitation —

LYDWINE: It’s part of the image we’re gifted with.

DYER: Yes, that’s right — there’s that aspect of the image that’s imaging God in time. Sabbath concerns what Heschel called the “architecture of time.” Just like God’s activity, our relationship with God, in a sense with space would be replicated or imitated in what happens in the Temple. Space is the Temple, which then for us becomes the Mystical Body and our own bodies. And then, in Christ, all space and time is caught up into eternity. He does the work of recreating — in His ministry and the carrying of the Cross and all the Incarnation, He does His resting in the tomb — and that allows for eternity, where our rest is not so much imitative as it is participatory. Because it’ll be the fullness, that life come to full stature, of Christ’s Mystical Body.

LYDWINE: Saint Augustine points to this at the end of The City of God, that we actually become the Sabbath in Heaven: “For we shall ourselves be the seventh day, when we shall be filled and replenished with God’s blessing and sanctification. There shall we be still, and know that He is God…”

DYER: Yes, I would say Augustine is very aware of the totality of the Body of Christ. Of course, all of this can be looked at under the rubric of what is the destination of the body? Ultimately and proximately. We’ve heard it our whole lives long, and we say it — “Rest in peace”. We say rest. The Eucharistic Prayer asks for the deceased a place of refreshment, light and peace. So the destination of the body, our bodies, is to be like God, to be at rest. Then proximately, what are the other rests? Well, you have to rest from work — but we’ve come into a time we’re so technologically advanced it’s often hard to distinguish between rest and work, and the celebration and non-celebration. There’s a way of Sabbath keeping that was a discipline somehow preservative of a deeper truth, and a deeper way of being, that meant something more than not working — just like when we say peace isn’t the mere absence of war, and silence isn’t merely not speaking. There’s something more. Rest isn’t inactivity. There’s a positive good to it — it’s not just an absence. We get to this point where in common parlance people speak about ‘killing time’ — now, that totally has to be a modern thing. Who would ever feel the need to kill time?

LYDWINE: We need to draw out the distinction between the Jewish Sabbath — as described in Genesis, as commanded in the Decalogue — and the Christian Sunday, the Lord’s Day, which really isn’t meant to be the seventh day, but actually the eighth day, or a new first. We run the risk of equating Sabbath with Sunday, as if the Lord’s Day is just our Sabbath — the same thing, but on a different day. But this greys out the necessary distinction, and obscures what we mean when we talk about the fulfillment of the Sabbath in Christ. It wasn’t a distinction yet lost in the early centuries of the Church — the Council of Laodicea, for instance, in the fourth century, actually forbade the double observance of the Sabbath and the Lord’s Day. And there’s an account of the death of Saint Columcille, the Irish monk, from the sixth century — he realizes he’s dying, and he tells his brothers, “This day is truly a Sabbath day for me, because it is for me the last day of this present laborious life, and at midnight, when begins the solemn Day of the Lord, I shall go the way of my fathers.”

DYER: Because we’ve lost the Sabbath as a category, it’s hard to see any fulfillment in relation to it. By way of a distinction.

LYDWINE: We’re doubly-damned in contemporary culture. We not only need to have some sense of what the Sabbath is, but how it might be fulfilled — to encounter something even greater than the Sabbath.

DYER: It’s interesting to read the Gospels with an eye toward what Jesus does on the Sabbath day. He heals, He gives signs of fulfillment, He gives signs of the body being freed. They’re ultimately signs that point to the resurrection and the new creation. The most gratuitous one to me is that, wait, Jesus heals a guy and tells him to go parade around carrying his mat on the Sabbath day? What does he need his mat for, if he’s healed? Why does he need that mat? He doesn't — it’s that Jesus wants him to be seen as doing something that can be taken as work on the Sabbath. That’s the provocation.

LYDWINE: Why would Jesus want that?

DYER: So that He would have occasion to wake us up regarding the Sabbath. So He could point toward the fulfillment of the Sabbath, for what it means in terms of our own healing. He’s showing what this is about. Isn’t He Lord of the Sabbath? That day, those people, the Jews — they’re indelibly marked by the Sabbath. We forget that as Christians we’re also indelibly marked. In Christ, when we celebrate the Lord’s Day, we enter into these deeper and mystical things, because when we do we’re acting in accord with our true nature, which has been modified by grace. This is hard for the world to hear now, because if you don’t believe in the power of Christ and the sacraments, even Christian religion is going to be reduced to a kind of ethical practice — which is also a point of Jesus regarding the interpreters of the law and the Sabbath day. It’s become about ethics, and it’s supposed to be about ontology, your being, your identity, your boundness to time in the Sabbath, to your place in the promised land — and then ultimately what’s open to us in Christ is that we’re bound to eternity. Because ultimately we’re not just about this world, even when we’re in this world. Remember that wild quote from Léon Bloy?

LYDWINE: From Le Désespéré: “Every man who begets a free act projects his personality into the infinite. If he gives a poor man a penny grudgingly, that penny pierces the poor man’s hand, falls, pierces the earth, bores holes in suns, crosses the firmament and compromises the universe. If he begets an impure act, he perhaps darkens thousands of hearts whom he does not know, who are mysteriously linked to him, and who need this man to be pure as a traveler dying of thirst needs the Gospel’s draught of water. A charitable act, an impulse of real pity sings for him the divine praises, from the time of Adam to the end of the ages; it cures the sick, consoles those in despair, calms storms, ransoms prisoners, converts the infidel and protects mankind.”

DYER: That’s really getting to it. That’s really what we believe about being within the Mystical Body — that helping the old lady cross the street echoes into eternity, because it’s done in and through your being, which is joined to the Mystical Body of Christ, always. In Dies Domini, John Paul II talks about these errands of mercy on Sunday that extend from the sacrifice of the Mass, as a visible sign of Eucharistic joy. To visit a shut-in, or visit the dead. Something to extend the blessing, to become a blessing to others on that day because you’ve received a blessing. The Eucharist is a blessing of presence.

LYDWINE: In keeping with the destination of the body — one of the striking claims Augustine makes in The City of God is that in Heaven, after we ourselves have become the Sabbath, there’s a bodily harmony promised us that’s really beyond our capacity to understand: “What power of movement such bodies shall possess, I have not the audacity rashly to define, as I have not the ability to conceive… One thing is certain, the body shall forthwith be wherever the spirit wills, and the spirit shall will nothing which is unbecoming either to the spirit or to the body.” It’s the gifts of the glorified body described by Bonaventure and Aquinas — subtilitas, agilitas, claritas, impassibilitas. All of this seems to point to a misapprehension in our contemporary ideas of what it means to rest. We kind of picture just sitting there on a cloud, like in a cartoon — but that’s not rest. That’s not leisure. It’s more of what we would consider play.

DYER: From everything I’ve read, throughout my life — there’s something that must be analogous to dancing.

LYDWINE: Like Wisdom dancing before the throne of God, in Proverbs.

DYER: The tradition is full of it. But I think it’s precisely correct that when a person is dancing, and dancing well, there’s a delight and there’s an experience of the body and soul as one. It’s a unity, it happens, it has a beauty, a movement, a fluidity, it’s delightful. But if you stopped in the middle of it and tried to parse it out it’d fall apart. Because it isn’t its component parts — it only is what it is when it arrives at its completeness.

LYDWINE: Heschel mentions the Sabbath not being an occasion for diversion or frivolity, that it aims toward collecting rather than dissipating time. But I think an overemphasized solemnity might be missing the point — given what we hope for in our glorified bodies, it sounds instead like a day for somersaults.

DYER: It’s not for somersaults only. The somersaulting has to be an overflow of the worship. This I think is something in Christianity we lost, and maybe very early on — that sense of agape. You can see where you don’t want the eucharistic liturgy to turn into a circus in any respect, but —

LYDWINE: But I think we do. Not some sort of undisciplined madness — but like the circus of the flying trapeze or the high wire, so that when we sit in witness we feel we’ve somehow moved beyond the bounds of human possibility.

DYER: Under that aspect I agree. But what I mean is that there has to be an overflow that’s free. You’re somersaulting on Sunday, but that happens after the liturgical — even though the liturgical has its own play, that’s true. What’s proper to Sunday, the Lord’s Day, quintessentially is the eating of the Eucharist. But then the rest of the week, your body in motion in the world is supposed to take into account offering. Are our sick and infirm, our widows and orphans accounted for and taken care of? You’re capacitated and nourished to do this by the Eucharist. That’s where you get these things from the saints — Pier Giorgio Frassati saying “Jesus comes to me every morning in Holy Communion, I repay Him, in my very small way, by visiting his poor.” Because the saints want more. The saints delight in the world as it is, they’ve enlarged their sense of what’s possible. So the poor — most of us can’t incorporate that into our leisure. “Those people have oozing wounds!” But for the saints, what’s happening here is tremendous, it’s adoration, it’s worship, it’s touching God, bringing joy and healing. So what are you doing when you dress someone’s cold and nakedness? What’s happening when you do that? Well, in one way you’re giving someone a taste of rest from those taxing realities of life, and in doing so you’re also giving them hope, you’re witnessing to a greater possibility. This is the work of a new creation, and you’re being allowed to share in it, allowed to be a gardener in a place that’s better even than Eden.

DYER: There’s the living from Sunday to Sunday that also in a sense mirrors the exitus-reditus, the coming forth from God and returning to Him, but also Christ coming forth from God in the Incarnation, taking us to Himself along the way and returning us to God. That is our constant engagement. If we don’t act in accordance with that, we’re striking against ourselves. If we had to put it into theological speak — in our orthodoxy sometimes we lose the fonts of orthopraxis, and those fonts of orthopraxis are the fonts of the truly mystical life. Sabbath, the Lord’s Day — that’s one of them. A preferential option for that which is hidden — that’s another. Penance and fasting. Silence. Meditation on the Lord’s Passion, coupled with offering it up. Seeing the corporal and spiritual works of mercy as integral to living the Christ-life as His Mystical Body. You know, something is lost when everything is subsumed under social justice. That’s ethical, that’s ethics. Yes, we need to be just, it’s true, it’s a virtue, it’s an important principle — but it doesn’t bring you to the side of Christ. What’s the reading from Saint Bonaventure, from the Feast of the Sacred Heart?

LYDWINE: “Imitate the dove that nests in a hole in the cliff, keeping watch at the entrance…”

DYER: It’s speaking of rest. Dove means peace, dove means reconciliation, and the cleft in the rock is the wound in Christ’s side, the wound of the Sacred Heart. The lance went up and through, and blood and water came forth — which is a sign of the baptism in which we receive the consecration, the ontology, the modification of our being, the belonging to Christ. And which is why, following Augustine and others, the medievals made eight-sided baptismal fonts, because that’s the womb in and through which you’re born into the eighth and eternal day. And that’s what gives you an entrée into the rest of God in eternity. Your whole life long you’re offering up your experience and everything in the created order in and through God as an act of worship, united to Christ the high priest through his Sacred Heart, which is the holy of holies, going toward rest but also bringing others to that rest.

LYDWINE: It seems that if we follow that exitus-reditus throughout the week, its ebb and flow, then we’re predisposed to welcome that Eucharistic presence, that Eucharistic rest, when it does arrive, and carry it within us. But if we don’t, if we don’t live oriented to that, if we don’t live with the expectation it’s reaching out toward us to gather us in, we’re unlikely to make that necessary offering. Because what happens on Sunday is something objective, something outside of us, I think that point has to be made — this is something happening in the architecture of time whether we offer observance or not. It isn’t just a missed opportunity on a personal level — it has consequences that redound upon the world. “Until the land has retrieved its lost sabbaths, during all the time it lies waste it shall have rest…”

DYER: When we get away from the news and the front page and the gossip, there are people who hear about Sunday and they almost want a part of it — they just don’t know how much of it they can enter into. Sometimes they’re not even sure, what is it all about? Do you remember that song, “Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down”? Johnny Cash had a hit with it. He talks about the contrast, and the loneliness of his body on a Sunday, because he’s sort of encountering there the loneliness of his hangover. I guess Saturday night is a therapy for the other five days of working. He has the beer for breakfast, one more for dessert, his head hurts, he has a dirty shirt, and out he goes —but he’s encountering the children playing, the daddy swinging the girl, the smell of fried chicken, the church bell, and it’s all making him feel alone.

LYDWINE: “…it took me back to somethin’ / That I lost somewhere, somehow along the way.”

DYER: But there’s a suggestion that in the aloneness there really is something else. That if he had it, he wouldn’t be alone. But he’s on the outside of Sunday, really.

LYDWINE: We’ve become that man, haven’t we?

DYER: Yes.

Abraham Joshua Heschel’s The Sabbath (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1951) is a marvelous book, and essential reading on the subject. For the relationship between the Sabbath and the Lord’s Day, see Pope John Paul II’s 1998 Apostolic Letter Dies Domini, as well as Francis X. Weiser’s Handbook of Christian Feasts and Customs: The Year of the Lord in Liturgy and Folklore (Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1958). Quotes from Saint Augustine’s The City of God are from Marcus Dod’s translation (Modern Library, 2000). Quote from Romano Guardini’s Meditations Before Mass is from Elinor Castendyk Briefs’s translation (Sophia Institute Press, 1993). Quote from Léon Bloy’s Le Désespéré is from John Coleman and Harry Lorin Binsse’s translation, as found in Pilgrim of the Absolute (Pantheon Books, 1947). Kris Kristofferson wrote “Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down” but it was Johnny Cash who took it to #1 on Billboard’s Hot Country Singles in 1970.

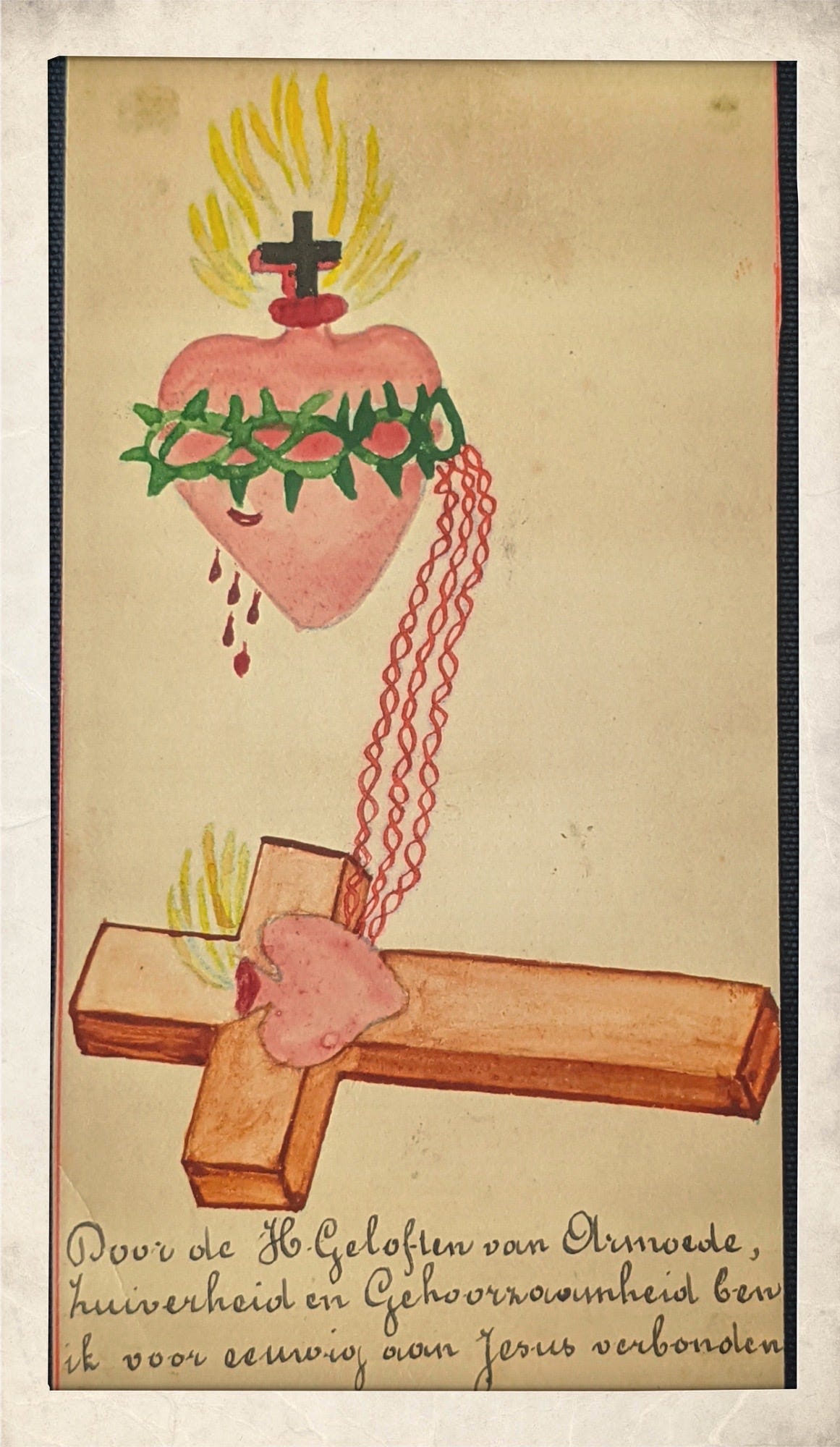

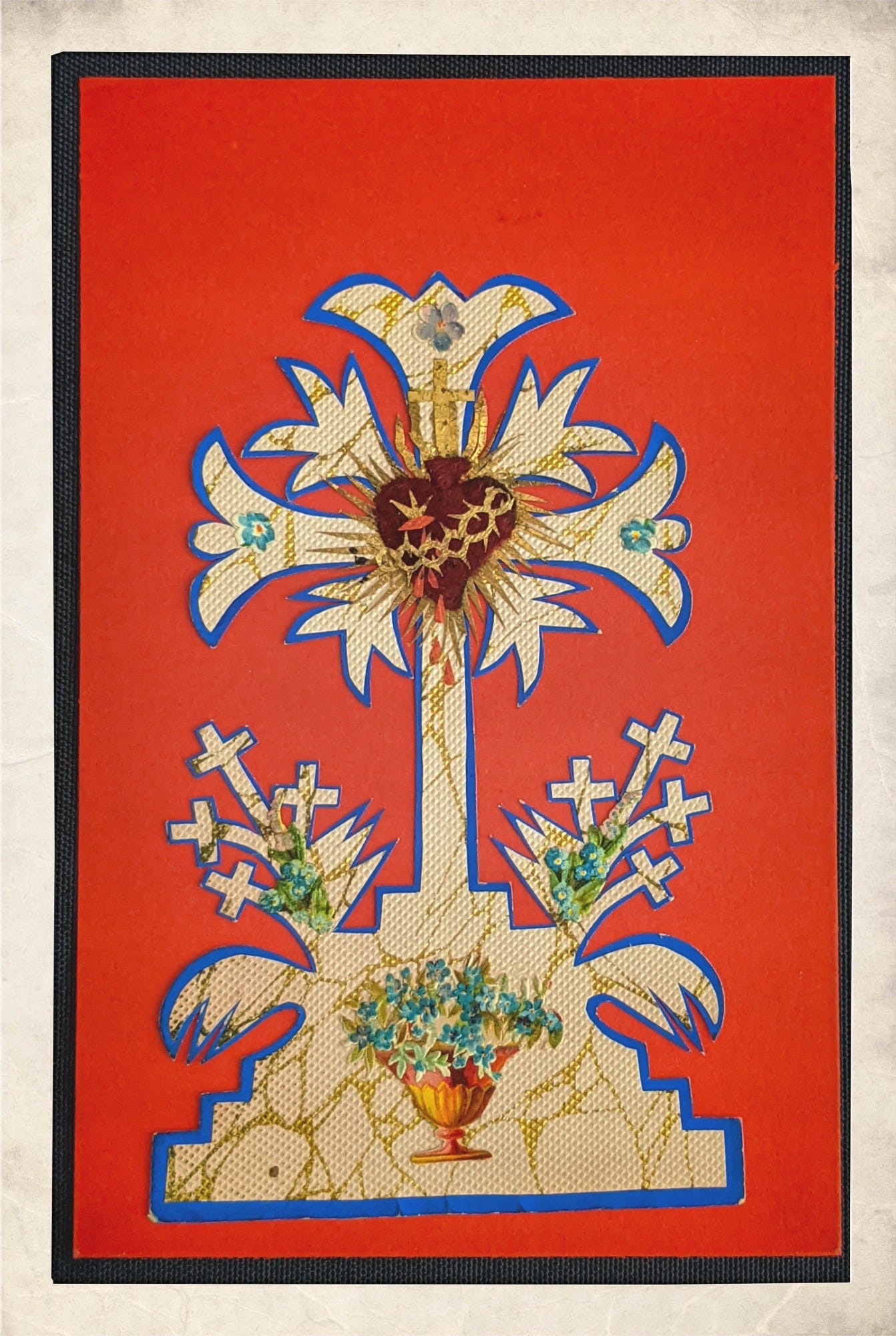

Sacred Heart images are from a private collection, New York City.