Anticipating a Christmas pilgrimage to the National Shrine of the Infant Jesus of Prague, east of Oklahoma City, Lydwine’s chaplain K.P. Dyer and our founder Brian Kennedy discuss Davis Grubb’s best-selling 1953 novel The Night of the Hunter, Charles Laughton’s acclaimed 1955 film adaptation, the glamour and mystery of evil, and Christianity as a True Crime Religion.

Their exchange has been edited and condensed for content and clarity.

DYER: I was mugged.

KENNEDY: In D.C.?

DYER: Yeah. They put a gun in my face — three guys. And they went through my pockets. They only got $20. I had an expensive pocket watch, but they weren’t interested in that. I was calm during it, and just after. I went to the police. Apparently, three guys that night stole a girl’s purse. Standing not far away were members of a band she played in — the band members chased the guys, and they had them up on a roof. The police took me, following up on what had happened to me earlier in the night — it was like two o’clock in the morning — to kind of ID these guys, but I couldn’t confidently say they were the same guys. I knew more the features of the gun. I told the police, “I’m sorry, I see human faces every day, it’s not every day I see a gun.” It being in my face, it was what I was concentrated on. Later on, it was somewhat infuriating to me that there should be such a violence. The fact that there were three of them — what do you need a gun for? Stupid kids, with a gun.

KENNEDY: We grew up, the two of us, in a very secure time overall, in the richest society and perhaps the safest society in the history of human societies — but, despite that, through experience or imagination, both still haunted and fascinated by the sense that something can go wrong. The sense that, underlying everything, is this mystery of evil.

DYER: Karen Wilson was an undergraduate student at the University of Albany who disappeared in 1985, when I was ten years old. She was beautiful, and for months on public access TV in Albany they ran her picture, played music — “Have you seen her?” It was a haunting expectation, that this story would unfold, but it never unfolded. There was never a body. The only details — she went to the mall, she went to a tanning salon, she was preparing to go on vacation, and that was it, no trace of her ever. She was kind of in my mind, my imagination, my prayers as a lost person. I don’t know, I guess there were some of us from that time, that place — and some probably more deeply than others — we had present to us a lost person, who has a name and a face, and who we didn’t know before, who in some ways shared spaces we must have shared at some point, who’s lost, who’s disappeared. That was a kind of space of years where a couple of things were going on. There was kidnapping, there was kidnapping awareness. They were making us aware of the fact of kidnapping — kids showed up on the breakfast tables, you know, the milk cartons. Obviously, the Adam Walsh case, and there were others. For a long time, much the way that for a while we became habituated to waiting to hear about the next terrorist attack — in those days, it was waiting to see who was up next to be abducted. But also, as a child, you had to somehow be aware that you too could be abducted. But the fact of someone disappearing without a trace is still… it’s a hole. It’s not something we’re ever kind of… it’s how I included that scenario, in praying the mystery of the Finding of the Child Jesus in the Temple... which is called a Joyful Mystery, but it’s one of the mysteries where it depends on when you walk in on it. It’s a deep horror for Mary and Joseph — their child is gone. They lived that. Mary lived that at the foot of the cross, as well. The death of her son, he rose again, but still this happened. It’s seared, that experience is seared. It’s there. She tasted those horrors. Karen Wilson’s family, I’m sure, drank deeply from the dregs of that, but for all of us who lived and were aware, we’ve always had the aftertaste of that, somehow, on our palate.

KENNEDY: A lady tried to kidnap me, when I was six years old. I was out walking, alone, and she tried to get me into her car. No violence, she just tried coaxing me in. I was a very shy kid, fearful, and kept on walking. At the time, I didn’t realize fully what had happened. I mentioned it to someone later in the day, offhandedly, and all hell broke loose. Got called to the principal’s office to talk to the police. That was traumatic enough — that brush with authority, with the blue men, as Grubb calls them in The Night of the Hunter. I thought I’d done something wrong. And of course, I’ve always wondered what might have happened to me, had I gotten in the car with her. If she would’ve hurt me herself, or brought me to someone else. Killed me, or kept me alive. Maybe tried to make me forget who I was, like Steven Stayner or Jayce Duggard. That latter possibility has always been much more frightful to consider — the loss of identity, subsumed by evil intentions. It still makes my heart race.

DYER: When you’re talking about someone like that — a serial killer, or whomever — you’re talking about a hunter. Especially with the vulnerable. Karen Wilson was small, only 5’3”. Another girl, who disappeared later, had a similar profile. They never knew what happened with her either. There’s the anxiety, is this strange happening going to become serial? Is there going to be a second instance? In the first instance, it’s kind of a consolation, maybe it’s someone who knew her. As awful as that is. These little consolations that are no consolation at all. We breathe a sigh of relief, maybe a disgruntled boyfriend — it’s not a hunter. I mean, what does a hunter do? If I went out once with a gun and bagged a deer, and someone came to me and said, “Are you a hunter?” “No, but I killed a deer once.” I don’t have the machinations, the training, the time, the culture of a hunter, who steps carefully into the woods, who needs to be camouflaged at times, who needs to go undetected in order to get his prey. Karen Wilson was about 1985. In 1987, from a close part of the parish we belonged to, another girl, she went missing, and her body was found. So, you know, say Karen Wilson was 1985, this is sometime in ’87, chances are it’s not even two years removed — they found her body but they never pinned it on anyone, and so perhaps not a serial killer but in a strange way similar to a serial killer because of going undetected. A serial killer only becomes serial because in at least one instance he’s gone undetected, and even a one-time murderer starts to feel similar to a serial killer because at least in this one instance he’s gone undetected.

KENNEDY: Because there’s not an explanation available, it falls into that realm where there’s an unease or fascination because we don’t know what’s going on, and because we don’t know what’s going on it might be something we can be drawn into, we can be made unsafe, we can be made part of the story.

DYER: Twenty years later I was visiting the cemetery where my people are buried, and walking along reading grave markers, and all of a sudden doing a double take because I’m at the grave of this other girl and the first thing I did was look up and look around, and that’s kind of strange — that’s kind of the reaction to the possibility of a hunter. This girl had gone missing in the neighborhood, and her body had been found, and killed by we-don’t-know-who, and there I am at the grave and I’m looking around in a defensive way, what if he’s around? If anyone was around, how would I know?

DYER: I had mentioned something offhandedly to a parishioner, about encountering The Night of the Hunter as a Christmas story, not knowing that he and his wife would get the movie, and of course thinking about it in too much of a conventional mindset, they were completely thrown. Because it’s hard in a popular imagination that’s not really going to look deeply at the whole of the work to get away from the conventional forms of looking at such conventions — one being the Christmas film, the other one being catch-the-murderer.

KENNEDY: In much of the secondary literature — mostly of the film, there’s not much about the novel — there’s always such a focus on Robert Mitchum’s character, on Harry Powell. The descriptions and synopses are all about the agency of Powell, as though he’s the protagonist. When clearly, especially in the novel, the protagonist is the boy, John Harper. It’s really a story about this little boy trying to protect his sister, and keep the secret of the stolen money, rather than a story about a demonic preacher figure. But Powell holds our fascination in such a way that he becomes a strange center of gravity in the larger narrative. His presence takes over and distorts our sense of what’s truly happening.

DYER: In the same way that the other secondary characters are taken in by his evil, because evil here makes itself sound like the Gospel.

KENNEDY: It makes itself sound like charity and love.

DYER: Like an angel of light.

KENNEDY: So, when you point out to people that The Night of the Hunter is a Christmas story, they’re often confused. They might say it’s a Halloween story, if anything, because it’s about a bad and evil man. It’s scary. But ultimately, no, it’s a Christmas story — and not just because it ends on Christmas. It’s about children finding hope, finding shelter — finding Rachel Cooper.

DYER: Rachel who weeps for her children, refusing to be consoled. She seems to understand children, at their essence, as those who are hunted. And because of that, in the Incarnation, Christ shares in being hunted. Becoming like a little child in a fallen world means you’re one of the hunted. But the hunter also has a double meaning — there’s Harry Powell, the serial killer, but also there’s something more akin to the Good Shepherd. Both of whom are a kind of hunter. There’s a way in which the shepherd is a hunter of the hunter, right?

KENNEDY: The shepherd is always on the lookout for those who would harm the sheep. There’s a reason why David can use a sling to slay Goliath.

DYER: Rachel is a shepherd — she gathers in sheep, lost sheep. The first thing she wants to do is wash them. Like Baptism. And Grubb uses a Hopkins poem as epigraph for that final section of the novel, a quote from “The Blessed Virgin compared to the Air we Breathe,” the universality of mother: “I say that we are wound / With mercy round and round / As if with air!”

KENNEDY: Which is of course not where the novel begins, and not where it spends most of its time. Mercy does not surround anyone. In fact, it’s quite the opposite — it’s greed, it’s violence, yet it’s all of these things somehow revealing mercy through the journey John takes. There’s a sense throughout that God is merciless. Early on in his characterization, John comes to associate God with the blue men who took his father away — God is bad, God is going to come and destroy my life, God is not a friend. If you judge by how the world runs, and how the children suffer, it seems the world is in the hands of a God who does speak to Harry Powell, and speaks Harry Powell’s language. Much like a kid who tortures animals, and grows up to torture people.

DYER: Which in some ways is what happened to Christ as well. I think of the lines from Edith Sitwell: “The wounds of the baited bear— / The blind and weeping bear whom the keepers beat / On his helpless flesh… / the tears of the hunted hare.”

KENNEDY: Brings to mind the film again, the flight of the children down the river —

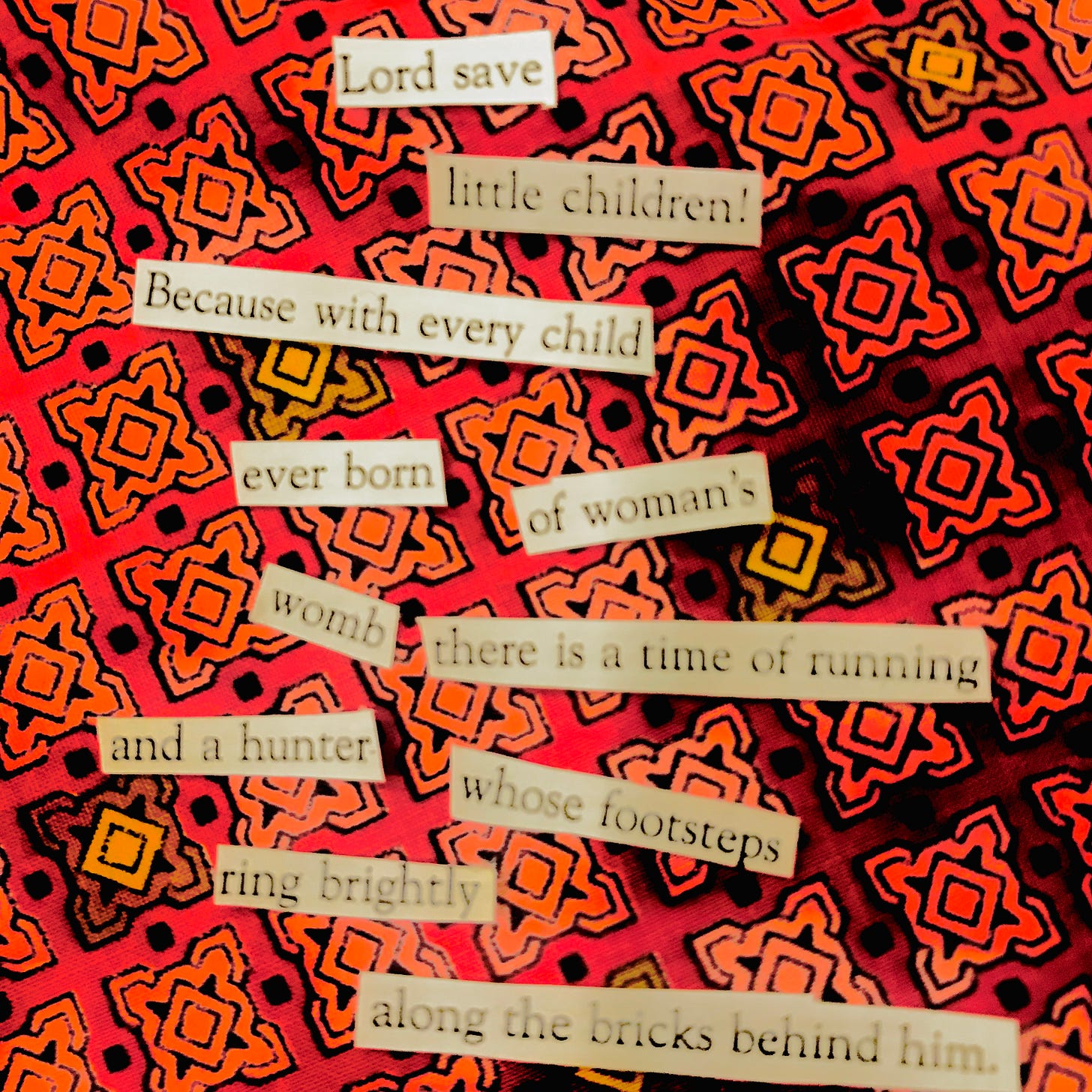

DYER: Right, where you see the attendant animals. In the novel, there’s also the clear association of the ticking of the pocket watch and the beating of the heart. It points to the Christmas story ultimately being at the heart of time. It all collapses into one another — the horror of the Holy Innocents gets taken up in the mystery of what happens before it, into the Nativity. In John’s recollection, it’s clear to him what the Christmas story is about — they must have been on the run.

KENNEDY: It strikes me that Ben Harper’s crime — what gets him hanged — is different from Ben Harper’s sin. He killed two men and stole money, and did that out of desperation because of the hopelessness of the time. But what he does to John is much deeper and harsher — he places a tremendous burden on this child. “Mind what you swore to do, boy!” In that burden, the father effectively sets the son running away from God. Overall, in both the novel and the film, there’s this split between those things people do because they’re desperate and they have no choice, and that other sort of behavior, that perversion, or wickedness, that finds its full flowering in the character of Harry Powell. I think of Bart the Hangman, who carries out Ben Harper’s execution. He does what he does, however unpleasant, to avoid another circumstance — death in a coal mine blast, his wife left a widow, his children orphans — that’s equally unpleasant. He’s driven to it, and its accompanied on our part by a certain understanding of the man’s circumstance and context.

DYER: But someone like Miz Cunnigham, the junk shop woman —

KENNEDY: Yes, she’s craven, her shop is stuffed, she’s doing fine, business is booming during hard times — but she wants more and more, she wants the stolen money. It’s a perversion outside of the immediate circumstance of desperation, it’s set in a larger circumstance of general human fallenness, of the human capacity for evil.

DYER: There’s a grotesqueness to Icy Spoon. She really is the most despicable character, next to Harry Powell — though it seems Powell might just be more outwardly awful, with the flashy clothes of a murderer. She’s just nasty. Driving people into these dangerous situations, berating her husband, leading the mob violence. She’s embarrassed they fell for him, but there’s also an evil there coming to claim evil. She’s not repentant — she doesn’t wonder how she could be so foolish. It’s, “He’s a liar!”

KENNEDY: There’s a lack of responsibility, very much like Adam and Eve in the Garden — the woman made me do it, the serpent made me do it.

KENNEDY: But I wonder — would John ever have been freed of the burden his father thrust upon him, would he and Pearl have found their true home, if not for Harry Powell? It seems there’s a lot of what amounts to failure and error, in human terms, forcing these children to run into the arms of real safety and real salvation. They’re driven out of a place of desperation and into a place of hope. But it’s entirely through adults being awful, paradoxically. For John, especially, that recapitulation of his trauma, of seeing the blue men come for Harry Powell — before that, he tells Rachel explicitly, “that’s not my dad!” — but seeing them come for Powell offers John this furious climax, where the original event with his father is brought back to him, and he’s able to find agency within it, he’s able to say no, I can’t do it, dad. What’s striking to me is after that moment there’s not one mention of the money ever again in the novel. It’s gone completely, it’s washed away. The burden has been lifted, it’s been obliterated.

DYER: I read somewhere — I still need to track it down — that Edith Sitwell was a hobbyist of serial killers. In other words, she was fascinated reading about them. Maybe it’s because — maybe there’s something vaguely or grotesquely poetic about what they do.

KENNEDY: I think there’s something to that, the performative element. It takes in the human capacity for gratuitous making, for no other purpose but delight. A certain macabre artistry. And we talk about the serial killer as one who kills again and again and again, but for the audience — and with the performative, there’s always an audience, there needs to be — it’s almost as though what’s serial is not the killings of the individual, but the expectation of the next one...

DYER: ...in the ongoing series. “I already read that installment.” Like phone upgrades.

KENNEDY: Something consumer-driven about the whole thing. The cultural fascination — Manson, Dahmer, Bundy, Golden State. “Which one is your favorite?” But still something very real, almost visceral. Worth paying attention to. Their rage become our spectacle. Though I have to say it’s all so much more troubling, the older I get. Having children, having spent so much time now caring for others. Knowing the full weight of what can be lost.

DYER: Sometimes the fascination has to do with a well-told story. Like H.H. Holmes, The Devil in the White City.

KENNEDY: Or Springsteen singing about the Starkweather murders on Nebraska.

DYER: Or sometimes it’s the gimmicks used — like the Zodiac — what year was that? He’s writing puzzles — that automatically somehow sets the mind moving. I mean, you already have that sense of mystery and the need to figure it out, and he explores it further by writing, what, these cryptographic things?

KENNEDY: There’s often a demented theatricality involved, like the dialogues between Henry Lee Lucas and Ottis Toole, lovers talking on the jailhouse phone, where there’s a back-and-forth — it reads like a play, like Beckett or Pinter or Chekhov: “I been meaning to ask you. That time when I cooked some of them people. Why’d I do that? / I think it was just the hands doing it... I’d have preferred you not talk about that. I don’t want people to look at us as that kind of person.”

DYER: They’re worried about how they’ll come off.

KENNEDY: Right, there’s a certain fussy propriety, completely outside any normal bounds of apprehension.

DYER: In some of these instances, they’re kind of racking up notches on a bedpost, and notches on a bedpost are kind of symbolic, kind of the evil side of preserving relics. There’s the uniting side of the relics of the saints, which is the connection of communion. There’s the relic-keeping of the serial killer that is something else entirely.

KENNEDY: It’s domination, not veneration.

DYER: And it’s private, too.

KENNEDY: Right, it’s not communion. It’s hoarding.

DYER: The Dahmer case is horrifying for that reason, and for human stupidity. The politics of apartment dwelling, of spheres of privacy. OK — you hear chainsaws and there’s a terrible stench, and you have an a-hole landlord who’s just too lazy, he’s about collecting a check and not about preserving a community of people.

KENNEDY: In remembering my way through these awful things, things I’ve read or seen or heard, and talking them over with my wife, we realized serial killing doesn’t hold any sort of fascination for her. What she prefers — not prefers, really, but what lingers in her imagination — are what I call “one-offs.” Like day-care workers caught deliberately picking up and dropping toddlers on the floor when they’re trying to nap, cruelty like that, and it’s just random, do you know what I mean? It’s just an explosion of violence, and then it’s gone. There isn’t much cause to linger. No plot, if you will. Even though, if you spent enough time with it, the violence could be situated in some larger context of story, some human sense of cause and effect. Which in a way is what our criminal justice system is designed to do — establish the story, the what-has-happened, even though only a fraction of those stories fully spill over into the popular imagination.

DYER: Are there any well known one-offs?

KENNEDY: It depends on how that’s defined. On some level the anonymity of these, the fact that there’s so many instances, one after another, you can’t keep track of them all, is what my wife finds so troubling. Human beings caught up in such cruelty would seem to deserve something more than a blurb in People. Maybe just let them alone entirely, give them their privacy. Let the judge handle it. But broadly speaking, if we’re just talking about individual instances, JFK is probably the most notable, at least in American culture. Once you boil away all the conspiracy nonsense, you end up with this young guy, he’s got an inflated sense of self-importance, he’s angry and ashamed, he can’t even get together the cash to buy his wife a washing machine. So, let’s show the world it can’t push Lee Oswald around, right? The repercussions of that are just astounding. Like Prufrock, “Do I dare / Disturb the universe?”

DYER: In the first instance of being told that story, and being surrounded by Kennedy death memorabilia, one of the immediate things that was puzzling and confusing is that there’s a series of murders involved. As a child, as it’s being explained, the death of the president — all of a sudden there’s this Jack Ruby piece, and you’re like, what? And it’s confusing. You see the photos, the blue men have him, how can he be murdered? There wasn’t really a good explanation. Or on one level, it’s not very interesting — Ruby felt bad for Jackie. When you say one-off, that was kind of his explanation. Ruby — he was pissed off, and he had a gun, and so he decided to go over there and take care of Oswald, right? But it’s kind of like, oh, that’s not very —

KENNEDY: Right, maybe you should rethink your charitable efforts, you’re not doing too well at it. The bizarre thing is that if you go to Dealey Plaza, and you go to the gift shop, they sell vintage tchotchkes, one of which is a Carousel Club pin, Ruby’s strip club, a replica of the pin he used to hand out to tourists when they came into Dallas, to get them to come down to the show. You can go and buy one — who the hell would buy that? It’s just the most bizarre thing.

DYER: Sometimes I think of Pranzini. He was an object of prayer for Thérèse of Lisieux. He killed three people — an upper-class prostitute, the maid, and the maid’s daughter. During its time, this was a cause célèbre all over the newspapers in France. Thérèse was praying for him, and she read in the newspaper that while going to the guillotine, at the last moment he asked the priest for a crucifix and he kissed it. She said that was a sign of a prayer answered for his conversion.

KENNEDY: I was in Fort Worth a while back, out walking. I came across this renovated space in a warehouse district — some artists had taken it over. Across the front was painted a giant rainbow mural of JonBenét Ramsey, that little girl killed on Christmas in 1996. I was stunned — I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. How could someone do that? With the face of a murdered little girl? It was indecent. I got quite angry. But then I had another thought — why did I even recognize her in the first place? Why is she even in my head? The poor thing — only six years old. My heart sank. I felt complicit.

DYER: An interesting communion of souls – the earthly and heavenly cities, entwined.

There’s often a demented theatricality involved, like the dialogues between Henry Lee Lucas and Ottis Toole, lovers talking on the jailhouse phone, where there’s a back-and-forth — it reads like a play, like Beckett or Pinter or Chekhov: “I been meaning to ask you. That time when I cooked some of them people. Why’d I do that? / I think it was just the hands doing it... I’d have preferred you not talk about that. I don’t want people to look at us as that kind of person.”