There Is Only One

Conversation with K.P. Dyer and Rachel Kennedy

...in which we discuss with our chaplain and our resident playwright William Friedkin’s 1973 masterpiece, The Exorcist, language as the armor of light, and the silence of Saint Joseph as Terror of Demons.

This exchange has been edited and condensed for content and clarity.

KENNEDY: I think I first saw the film when I was six —

LYDWINE: I can’t imagine —

KENNEDY: I know, right? I’d never show it to my kids — they can watch it when they’re grown up and on their own. I remember carpooling to CCD, and telling another girl how Regan’s head spun around. I didn’t think anything of it, I was just chattering away. Her father finally said, “Please stop, you’re frightening my daughter.” I turned to look, and she was terrified. Her eyes were bugged out.

DYER: I don't know if you ever saw a certain holy picture Catholics sometimes had in their homes. It was Veronica's veil, kind of painted with a certain optical trick. You could go up to it and pray an Our Father and see the eyes open. The artist was Gabriel von Max, an Austrian painter, who belonged to some creepy Theosophical Society. He had done this painting and then it was widely reproduced — my grandmother had one of these, the neighbors had one of these. It was a common thing to find. Barbara, one of our neighbors, she was in her mother's kitchen reading The Exorcist. She said the picture fell off the wall, the glass broke, and she never finished reading the novel. I don't know if she ever saw the movie or not. And it wasn't just lore. One time when I was in their home, I checked — it was the image in the frame, but the glass was gone. That was The Exorcist story from my neighborhood.

LYDWINE: Why is the casting out of demons so central to the messianic mission of Jesus?

DYER: It marks the close of an era and the beginning of another. The Fall, the time of the reign of evil, is now met by the action of the Messiah. So it kind of belongs to the eschatological signs of Christ that point to a future fulfillment. Just like you have miracles that point toward a physical restoration — and, as the Creed says, the resurrection of the dead — so too there's the casting out of demons, showing that in the end they’ll be parted from the company of the saints. It’s a sign of the inauguration of the end times, the end times meaning two things — in one sense you can speak of the end times meaning the very last moments of possible time. But also the end, meaning the fulfillment. The inauguration of the eschatological age. The last things. One of these is the casting out of evil. Because the best those forces can do is to try to frustrate the designs of God. With the intelligence of angels, they must understand they can't have it over God, but they can menace, they can try to draw people away from Him. With demonic possession, the demons in those situations — it seems they have to manifest themselves, which then really marks the beginning of their end, their casting out, which then glorifies God.

LYDWINE: In the third act of the film, after Father Merrin, the elderly Jesuit, shows up, there's a telling exchange between him and Father Karras, the younger priest, who’s also a clinically trained psychiatrist. Karras tells him, “I think it would be helpful if I told you told you some of the personalities Regan has been manifesting — so far there have been three.” Merrin stops him short and says, tersely, “There is only one.”

KENNEDY: I love that moment. After all Karras has seen. Because his crisis is a crisis of faith — he's so reasoned he can't see the supernatural when it's right there in front of him, which is incredibly dangerous.

LYDWINE: Because unless he's able to name it, unless he's able to whittle down the three to the one, he won't be able to fight.

KENNEDY: When I was growing up, my best friend had a Ouija board, from Parker Brothers —

LYDWINE: — like what's in the film, what Regan uses. We had one of those, too.

KENNEDY: I remember playing with it right outside her house — on a tree stump, with two chairs. Afterward, I rode my bike home and told my mom “Oh, I just played this really great game.” When I told her what it was — my Mom was Irish-Catholic from Massachusetts, she had these catchphrases — she said, “You ready for this? I'm here to tell you — you play with that thing, demons can get in you!” She just scared the living daylights out of me. But I was given the language I needed — that the things you do matter, you know? What you play, what games you play, matter, what you call upon matters — don't mess around with it. Most of the characters involved in the film are vulnerable because they don’t have a name for what’s happening. The Church gives you a language so that you’re protected, so that you can put on the armor of light. Chris MacNeil doesn't have that. Father Karras has turned away from that. And for Karras, without the right words, he’s fighting the wrong thing. He's still trying to look at it as a doctor —

LYDWINE: There’s even a moment when he makes the case for exorcism to his superior, and the superior asks him directly if he thinks Regan is possessed. He says, “I don’t know — but I’ve made a prudent judgment it meets the conditions set down in the Ritual.” It's a very symptomatic diagnosis — there is this, this, and this, therefore it must be that — even though I don't believe in that.

KENNEDY: Whereas Father Merrin looks at it as a priest, and sees it for what it is, and so can finally get to work.

DYER: Merrin is the proper diagnostician in this case. A doctor can describe all kinds of secondary things that may be happening because of this kind of a presence, but in this case the exorcist discerns and names the cause, and brings forward the remedy.

KENNEDY: Karras has trapped himself, in a way — “The demon has to do XY and Z for me to believe it's really a possession.” One of the things Merrin says is that the demon lies, and mixes truth with lies to confuse. Because, as you said, in the end the demon doesn't want to be drawn out — because that shows God's glory. So while revealing one thing it hides another in order to confuse, to continue to confuse.

LYDWINE: “If I react to that tap water like it's holy water, he'll still doubt. But if I do everything a demon should do in the face of a priestly investigation…” Well, it remains to be seen if Karras would accept something like that — because he’s much more susceptible to the seeds of doubt than he is open to the truth. He’s looking for signs of possession, but in a very real and dangerous sense he’s not even open to the possibility. It all plays out in this context, and the demon surely knows this is not only an opportunity to destroy an innocent girl, but to destroy fully the faith of a priest — a two-for-one sale, as it were.

DYER: It's also interesting because, “Oh look, the priest is coming at me — but not with the arms of the church.”

KENNEDY: There’s a moment with the mother, Chris MacNeil, when she says “Can't you just see her?” and Karras answers, “Yes, I can — as a psychiatrist” and she screams at him “Oh, not a psychiatrist! She needs a priest! She's already seen every fucking psychiatrist in the world and they sent me to you. Now you're gonna send me back to them?” It's a wonderful moment because that's how Karras leads in every exchange — as a doctor, not as a priest.

LYDWINE: She goes on to say “Jesus Christ, I need a priest — won't someone help me?” There’s inadvertent praise in her blasphemy. It’s cursing, but —

DYER: It’s a cry of pain.

DYER: Father Merrin finds something strange at the beginning of the film, at the archaeological dig — a medal of Saint Joseph. He's looking for artifacts and he finds this one that's out of place, that doesn't belong —

LYDWINE: “Not of the same period,” the other archaeologist says.

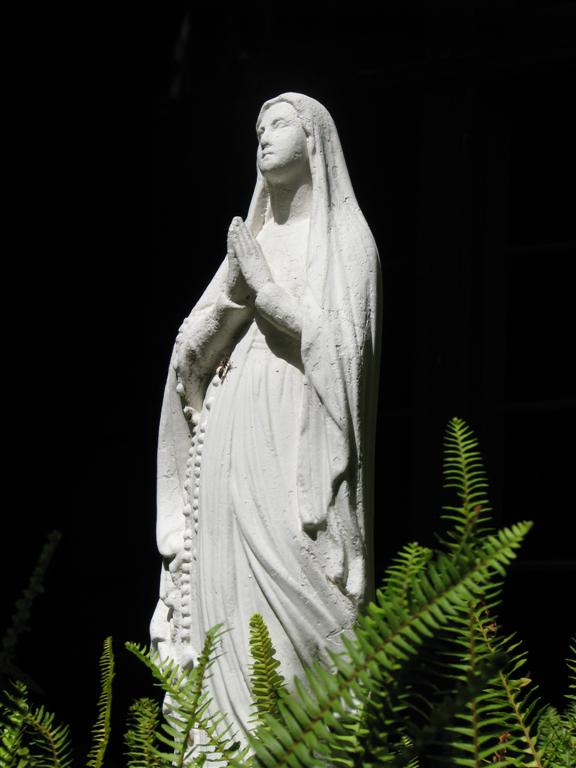

DYER: Yes, but not in the novel, either — it's something introduced into the story for the film by Friedkin. The medal shown throughout is very stylized, Fernand Py’s representation of Saint Joseph from the 1930s. It says in Latin — which is also the language of the Ritual — it says Sancte Joseph, Ora Pro Nobis — Saint Joseph, pray for us. In the Litany of Saint Joseph, there's a line referring to him as Terror of Demons. The question comes up, and I'm not sure I've ever found a lot about this — why call Saint Joseph the Terror of Demons? It's an interesting question. Saint Joseph defends the Blessed Virgin and the Christ Child from Herod, who pursues the Holy Family. But I think, too, there is in fact something about the silence of Saint Joseph that speaks of obedience, rather than the disobedience of the evil spirits. There’s a quote from Auden’s For the Time Being, his Christmas Oratorio: “No, you must believe; / Be silent, and sit still.” That’s the Archangel Gabriel to Saint Joseph. The silence itself, when you speak of Saint Joseph, it seems to hint toward a kind of consecration, the quality of which is silence. It's about serving the Holy Family. Interesting too, in the mystery of the Finding of the Child Jesus in the Temple, Mary does the things that are closest to what we would call a parental reprimand — it's not Saint Joseph. Saint Joseph is silent. It brings Milton to mind, as well, “They also serve who only stand and wait.” That’s a tremendous line. It speaks toward what would be, in the Christian tradition, the virtue of vigilance, it has to do with watching, with watching in the night, and watching also meaning and having here a kind of protective function. Joseph is called the guardian of the universal church — there's something protective going on. It’s interesting to think of this medal first showing up in the film out of sight and far away. Merrin seems too intuit this as saying something meaningful, that he's going to have to do some work he's had to do before.

KENNEDY: He knows, yes. So much of Christianity is in waiting — like Joseph, Merrin hears the call, but his call is really to wait for the next call, to be ready. All he knows is that he has to go back, he has to go home, and then he just waits. When he finally gets the message, he doesn't even open it — he knows as it's handed to him. He knew it was coming, he just didn't know when.

LYDWINE: The medal of Saint Joseph also stands in contrast to the other artifact they find at the dig, which is the amulet of the demon. The archaeologist explains it would’ve been used as evil against evil — it was meant to be worn in the same manner as the Saint Joseph medal, as a protection. Only they seem to be — and obviously are — something very different from one another. When the archaeologist points out they’re not of the same period, he’s not only saying something objectively about the contents of the archaeological dig, but also talking about something in the nature of cosmic history. With Christianity, something new has entered the picture. No longer evil against evil, but the triumph of sacrifice and obedience. The two artifacts and two eras are juxtaposed with one another, but there’s a further juxtaposition when we see the medal again, in Georgetown, in late twentieth century American civilization when Christianity is no longer seen as something new, but rather as an anachronism, and finds itself in opposition once again.

DYER: There's a lot of noise in the film, noise that's meant to be disturbing, overwhelming. It reminds me of what Lewis wrote in The Screwtape Letters, about Hell being “occupied by Noise.” It would be interesting if one could listen to the entirety of a noise soundtrack of this film, including the music — Oldfield’s “Tubular Bells” toward the beginning, Henze’s “Fantasia for Strings” over the end credits — but none of the spoken language.

LYDWINE: There’s constant noise at the beginning in Iraq — the pounding of the picks at the dig site, the blacksmiths pounding the metal, the galloping horse — all of these very rhythmic, overwhelming sounds. Of course, this is also a man, Father Merrin, with a heart problem — these sounds perhaps echo what’s in his head, the pounding of the blood. Then the sudden silence of the office where he's with the other archaeologist, the stopping of the clock — this seems to be the thing that sets him in motion. He's been uneasy the whole time, but this is the moment of full realization, that something is coming. He goes back out to the dig site and has his confrontation with the statue of the demon, positioning himself between the demon and the man, accompanied by the awful snarling of the dogs. This overpowering noise comes back when he's in Regan’s bedroom toward the end — things start slamming and flying around, shortly before he dies. All of this noise, this emphasis on noise and its cessation, is the outward sign of Merrin’s realization that the proverbial clock is about to stop for him — that he's going into battle, going toward death. He seems to know not only that something is coming, but that he's not going to make it through, not in this world.

DYER: When people ask about my favorite part of the movie, I know it’s disappointing to some people — I say any scene with Lee J. Cobb.

LYDWINE: Especially that finely played scene between him and Ellen Burstyn, the autograph scene, where each is trying carefully to probe the other for information, without giving away their own secrets.

DYER: As Kinderman, he has a dexterity in dealing with the subtleties of the psychologies and personalities involved, but he seems convinced from the beginning that there is something evil going on. As an investigator, he deals with facts — but he's not the kind of man that Father Karras was becoming, leaning toward a kind of arrogance or despair in which the only acceptable things are what are called scientifically verifiable facts.

KENNEDY: Kinderman wouldn’t be good at what he did if he were bound by unbelief. His outlook allows for other possibilities. He lets the facts themselves suggest — what else could this be?

LYDWINE: He seems to have an instinctual sense he’s involved in something in which the methods of his world, police methods, won’t offer the best possible outcome. He hangs back, ruminating, waiting to see how this thing might be resolved before he has to make his final move. Because what’s he going to do, barge in and arrest the girl? That’d be quite a night in the lockup. So he allows these other people to get in front of him and move the situation along — and it's funny, but he actually shows up at the very end. He rings the bell for another chat, and the sense is that this time the gloves are off. So he's there for the climax, and then, in the end, for the denouement. Only he and Father Dyer are left, walking away together, in an almost Casablanca moment — the beginning of a beautiful friendship.

KENNEDY: The autograph scene is when Chris MacNeil begins to understand what her daughter has done — killed Burke Dennings. She’s hearing what Kinderman is saying and putting two and two together. It’s right before—

LYDWINE: The crucifix scene.

KENNEDY: Yes. I’ve thought a lot about the crucifix scene. It’s so intense — especially now, watching as a parent. Is it necessary for the film? Honestly, I don’t think it is — it’s simply too grotesque, too overwhelming, especially when you consider there’s a child involved. The sexual nature of it is just too much. I mean, I understand how it’s supposed to function within the narrative. Chris MacNeil, this affluent woman, this successful woman — she's not just an actress, she's a movie star. She has the best of everything, but still had no idea what would come down on her family. This scene is where she’s forced to realize it’s no longer her daughter she’s dealing with — this is something else, something other. A murderer, a blasphemer, something unspeakably cruel. She makes that explicit, in the next scene, when she first meets with Father Karras: “You show me Regan’s double, same face, same voice, everything. And I’d know it wasn’t Regan. I’d know in my gut. And I’m telling you that thing upstairs isn’t my daughter.” She’s actually come to a place that Karras will only get to in the last moments of his life. But overall, the obscenity… in the end, it’s just a movie. So to subject your actors and your audience to this, even if you’re trying to be faithful to the novel… Some things just aren’t meant for the screen.

LYDWINE: I think of the crucifix scene, trying to come to grips with it, in light of another moment, later in the film, when the two priests are slowly making their way up the long stairway to begin the exorcism. It’s the Way of the Cross. The women are there, weeping. You can hear the demon bellowing in the room above. The priests look like they’re going into battle, toward imminent death. But Father Merrin stops in front of Chris and asks, gently, “Mrs. MacNeil, what is your daughter’s middle name?” She answers, “Teresa,” and he tells her, “Regan Teresa MacNeil — what a lovely name.” Ellen Burstyn really nails the reaction, you can see his kindness smash through her despair — because he’s reminded her of the beauty of her daughter, her little girl, in this incredibly ugly moment, in this long ordeal.

KENNEDY: He gives her back her daughter’s humanity.

LYDWINE: He breaks the influence of the demon over the rest of the house in that moment. By his presence, by his kindness, he begins the work of healing and gathering, as Jesus does in the Gospels.

DYER: For the priests, there’s a Josephite work to all this. They’re helping to rescue a child from evil, as he did. It’s one of the reasons I think he’s called the Terror of Demons, because the demons always try to be a plague upon God’s children.

KENNEDY: There’s that wonderful scene on the stairs, so beautifully shot, Merrin and Karras sitting near one another, and the house is quiet. Karras asks, “Why? Why this girl?” Merrin answers, “I think the point is to make us despair. To see ourselves as animal and ugly. To make us reject the possibility that God could love us.”

LYDWINE: That God could actually love the beggar in the subway who stinks of piss, or the old woman who dies alone in her apartment and isn’t found for days. But to be a priest, to be the one charged with witnessing to this for the rest of us, offering the sacrifice — it seems an almost impossible burden for a man to bear. When Karras is making his way toward his mother in the psych ward — and her name is Mary, of course — the crowd closes in on him, it's like the crowds of the sick and the lame surrounding the Lord, overwhelming. They actually grab Karras, grab hold of his collar and tear it away. There's an emphasis on the power of his priesthood, even as he's just a son, struggling, upset, trying to get to his mother.

KENNEDY: At the end of the film Father Dyer comes to the house as they're leaving. Chris tells him that Regan doesn't remember anything, but when Regan comes out and she's introduced to him — she looks at him, but she doesn’t look at his face, she looks at his collar, the camera lingers for a moment on his collar. She obviously does remember something, because she reaches up and she kisses him.

LYDWINE: Because ultimately it’s not the man, it's the man-behind-the-man, it's the man who’s been given power by another to cast out demons and heal the sick.

KENNEDY: In that final scene, before Karras dies — it's a recovery of his faith.

LYDWINE: Yes, because in that moment — when he says “Come into me!” — it's a complete acceptance of the objective reality of the situation. There's something in the girl that's not the girl. Get the hell out of her and come into me. I've got a plan, we’re going for a ride. We watch Father Karras throughout the film training like a boxer — hitting the heavy bag, jogging on the track — and the whole time we think he's doing this because he's keyed-up and frustrated, but really what he's doing is preparing for this moment. He's no longer concerned with diagnosis or personality disorder — he’s remembered he’s a fighter, and so he fights.

KENNEDY: And there’s another priest at the bottom of the stairs, to offer absolution.

DYER: His last moments, his final confession. That's a very moving scene for a priest to watch on film.

KENNEDY: How so?

DYER: It's like a comrade who's fallen doing good in the line of battle, but who still needs some kind of care. There's always an ambiguity in our goodness in life, and what kind of completes us is Christ Himself, the presence of His grace. And yes, there's tears for the friend, but he sticks to what he does as a priest.

LYDWINE: It's the most important thing he can do for him in that moment.

KENNEDY: It's the only thing.