W.W. and the Dixie Dancekings

...or How to Search a Sow's Ear and Find a Silver Lining, in Spite of the Forces that F*ck You So Bad

The following piece, written on spec for Rolling Stone magazine in 1975 by our friend and mentor Stanley Booth, details the trials and travails of his own friend and mentor, the Memphis blues musician Furry Lewis, after Furry took a cameo role in the otherwise forgettable B-movie W.W. and the Dixie Dancekings, released by 20th Century-Fox in the spring of that year with Burt Reynolds in the starring role.

Stanley rightly championed, in this cautionary tale of Furry and the ill-fated Dancekings, that genuine affection for helplessness at the heart of American music, the plainest recognition that even if suffering cannot be conquered it can be endured, and so transfigured - that even broken hearts are meant to celebrate.

Stanley’s piece was accompanied, upon submission to Rolling Stone, by a cover letter (addressed to Jann Wenner, the magazine’s publisher) typed painstakingly in the blank spaces of an official Record of Death form from the John Gaston Hospital in Memphis. The movie in question, Stanley admitted to Wenner, “was and is unreviewable, but the enclosed needed (as you’ll see) to be written. It turned out to be more and better than either of us could have expected. I didn’t have time to make the handsome lace border it deserves. It costs $500… I am keeping (as you’ll also see) none of the money, but will use it to do God’s work. Your job is to see that it gets printed nicely and to pay me quick so I can get the money to Furry and do what I talk about doing at the end of the piece. I’m sure neither of us wants to be the last man to fuck Furry Lewis out of a chance to do a thing that he wants to do and that will bring joy to him and to whoever hears it.”

The letter, signed with the initials of the Okefenokee Kid, Stanley’s nom de plume, contained also the requisite bitching about never being paid his worth, complaints regarding persistent typographical errors in his pieces for the magazine, and also a promise that the writer was hard at work “collecting stories to tell… things I can’t even mention now, such as what happened the other night when Sam Phillips got fed up trying to send telepathic messages to Gerald Ford and called Fidel Castro.”

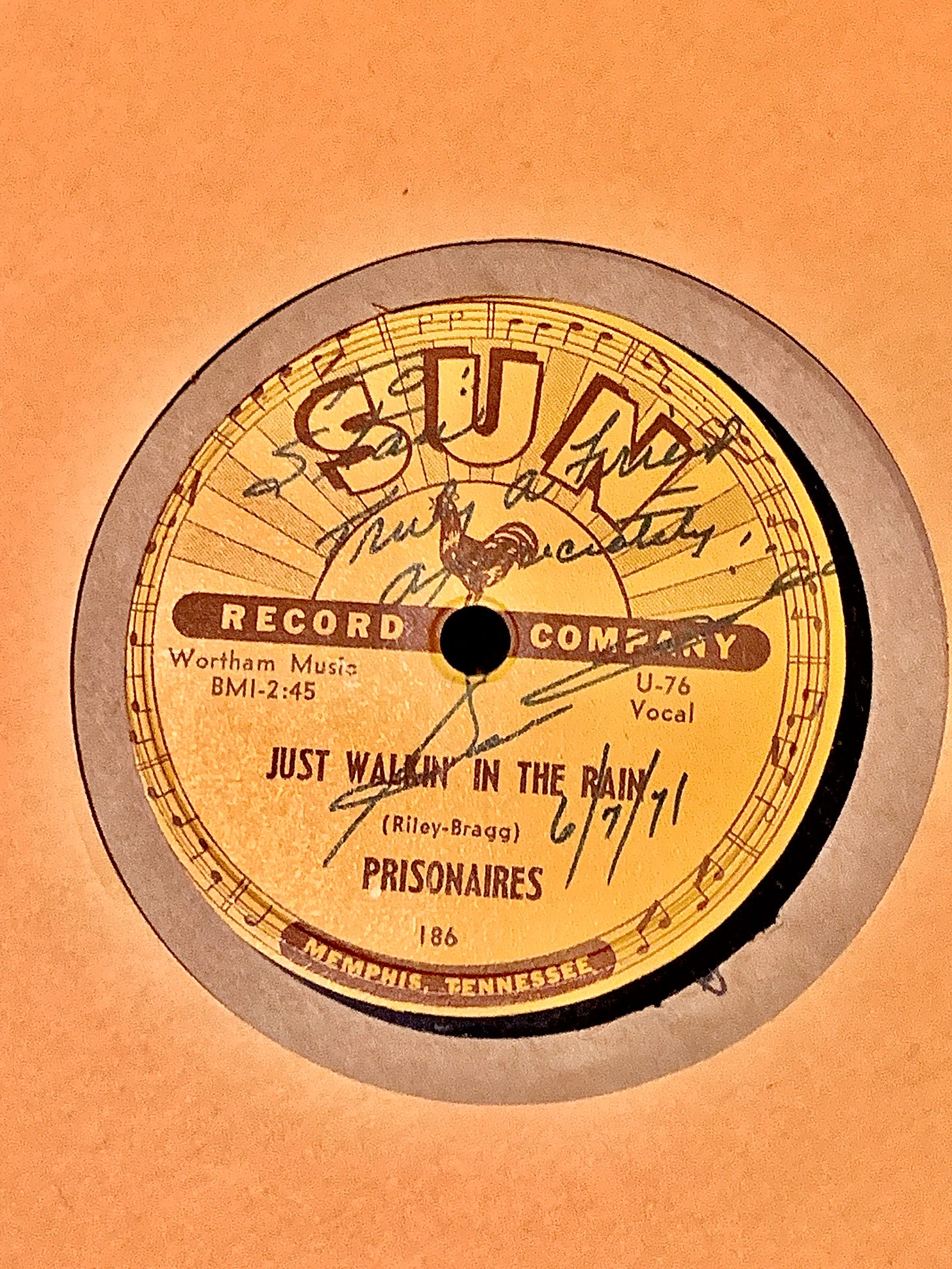

Stanley seems to recall that Rolling Stone did indeed run the piece as requested. Our search of the relevant archives, however, suggest otherwise. It is worth noting that when the cover letter to Mr. Wenner was discovered in Stanley’s official archive - a cardboard box beside the chaise lounge in his living room - it was tucked underneath a Sun Records 78, the Prisonaires’ “Just Walkin’ in the Rain” autographed by Sam Phillips himself.

“He won’t hurt you,” another writer once remarked of our friend Stanley Booth, “but he might get strange.”

Ten years ago, when I met him, Furry Lewis, one of this country’s most magical musicians (I have seen him hypnotize sober people into believing that his guitar is playing by itself, alone on the floor, spinning. Before your eyes.) was working as a street-sweeper in Memphis, Tennessee. He was over seventy then, and a few years later he retired, after working for the city of Memphis more than forty years, with no pension. But Furry has spent most of his life making it through hard times.

This century’s early years of sin and celebration, when with his contemporaries Furry played in Beale Street sporting houses, on Mississippi River steamboats, on medicine show wagons and on records with labels like Bluebird and Okeh, did not last long; Furry’s street-sweeping work enabled him to survive the Depression, the passing of the steamboats, the World War II recording ban, and the political warfare against Beale Street that has in every name from moral reform to urban renewal leveled some of the richest blocks of the world’s musical history, wiped them out as completely as any part of Hiroshima or Dresden, until now Furry is almost all that remains of an era.

I have never known Furry to turn down what he calls “a play,” though he has received neither the money nor the recognition due him. For the Leon Russell television special my New York liberal friends liked so much Furry was paid scale, or as little as the law allows. The Ash Grove in Los Angeles didn’t pay him at all and burned down. “I ain’t sayin’ it’s any connection,” Furry says, “but that’s what happened.” Furry’s perseverance (“Give out but don’t give up.”) has made him better known now than when he was young. The Memphis Music Association gave him a special award, a recent governor made him a Tennessee Colonel, whelps with tape machines descend on him, record his music, pay him as little as he will take without calling the law, and go back to Transylvania or wherever royalties don’t come from. He is photographed by a Chinaman for Playboy.

And then someone in Nashville calls to say that 20th Century-Fox are going to make a movie there, called W.W. and the Dixie Dancekings, with Burt Reynolds and a lot of Nashville musicians, and they need someone to play the part of an old blues singer. The movie’s writer, a Hollywood Kentuckian named Tom Rickman, comes to Memphis to meet and tape-record Furry. If the studio people like Furry on tape, they’ll have him come to Nashville for a live audition. Furry sings for Rickman and tells Rickman of the many times he’s been screwed by people with tape recorders. Rickman gives Furry some cash and, so it seems, promises him more money to come.

I was reading a copy of the script that Rickman had brought along. It concerned the fortunes of W.W. Bright (Burt Reynolds), a small-time con artist and stick-up man in south Georgia circa 1957. The Dixie Dancekings, a rockabilly band with a girl singer, follow the fast-talking W.W. to Nashville, hoping he can help them become stars, but W.W.’s con runs out and so does the band’s money, whereupon they join W.W. in robbing a bank, fail in the attempt and are forced to hide out at the place where the Dancekings’s leader (Jerry Reed) was reared, at the country shack of the old blues singer, whose soul rubs off on them and they make it big at the Grand Ole Opry.

It was a small story (not quite so small as I’ve made it here) and derivative of writers like William Price Fox and Charles Portis, but it worked. The opening scene was at a drive-in movie, W.W. in the back seat of a ‘55 Olds with a waitress whose red panties bear the inscription Friday, while on the screen as Christ in The Robe Victor Mature is crucified, arises from the dead and ascends to Heaven. With a few very funny shots - the noble profiles of Victor Mature and a Studebaker - it said quite a lot about human folly in America in 1957. I told Rickman I liked the scene, and he said it was one of many that the studio was having changed by a re-write man because the pre-production team had shown the script to such Nashville gentry as Roy Acuff and Tex Ritter’s widow and then asked permission to film part of this filth in the Ryman Auditorium, the Home of the Grand Ole Opry.

Rickman, the tapes of Furry in his pocket, drank a pale airport scotch in Memphis and went away, and so did his story.

CUT to Nashville, the Holiday Inn, outside in the rain that fantastic replica of the Parthenon them crazy hillbillies have, inside in the gloom Furry and me and people in denim and turquoise looking us over as if we are art objects. Furry, who is crippled and has had cataracts removed from both eyes, is sitting on the bed. Crouched beside the bed holding a tape recorder is the movie’s director, Jon Avildsen, whom Furry has confused, because by now most all people with tape recorders look alike to him, with the script-writer who’d promised him more money: “This the same man,” Furry is shouting across the room to me. “This the same tape recorder.”

Avildsen, who directed Joe and Save the Tiger and other things, is waving his little hands, saying, “I don’t know anything about that,” keeping the tape recorder pointed just right at all times. The location director stands up, turquoise jangling, kisses everybody in the room except Furry and me and leaves. Avildsen tells Furry that they need a song for him to sing as W.W. and the D.D. are speeding away from the police down the highway, going to Furry’s shack in the country. Furry changes tunings, thinking fast, and sings:

Talk about yo' travelin' You ought to seen a friend of mine When it come to travelin' That man was satisfyin' He traveled, he traveled, he traveled all around He never stopped his traveling till the police cut him down.

The tone, light but deadly, was just right for the old country singer in the story Rickman had written and everybody except Rickman himself, maybe, and Furry, had forgotten. The song disappeared into Avildsen’s tape recorder, never to emerge. But Furry played the guitar with his elbow, made it play by itself, said “Don’t worry about a thing. I will make a good movie,” and the people in denim and turquoise seemed to believe him. They wrote him a letter of general intent obligating nobody to anything, and we went back to Memphis.

Time passes. Furry hears nothing more from 20th Century-Fox. Then, from out of somewhere, Allen Ginsberg comes to Memphis to visit a university, and while he is in town he stays with a man who owns so much cotton that to him Chou En-Lai is just another egg roll. This man is called by his acquaintances Hornblower. Wanting Ginsberg to have the finest kind of time Memphis offers, Hornblower brings him to Furry’s house.

Ginsberg of the Blake-visions, mystic vibrations, cosmic illuminations, enters carrying a kind of wooden lap organ. Furry started to play and Ginsberg started also, but he was plainly out of tune. “I’m in Spanish,” Furry told Ginsberg, referring to one of his many tunings. “But I can get like you.”

“I think I’m in Mexican,” Ginsberg said, putting the lap organ away under his chair.

“I’ll tell you baby, like the Dago told the Jew,” Furry sang, “You no like-a me, I no like-a you.”

Ginsberg, who later sang an ad lib song to Furry that began, “Thank you, O King,” was properly respectful, which is more than we can say for Hornblower, sitting on the arm of Furry’s couch with his shoes on the cushions. Furry called me to the bed where he was playing and told me to have the man move his feet. I invited Hornblower into the kitchen, where we discussed his feet and I told him to give Furry some money for the poetry lesson - “No,” I said, wanting to have it clear who were the students here and who was the master, “Have Ginsberg give him the money.”

It was days later that I was by Furry’s and learned that Ginsberg had passed to him from Hornblower a twenty-dollar bill, not enough to pay for Furry’s beer and whiskey that Hornblower and his entourage had drunk. Furry had heard no further word from 20th Century-Fox, and he was getting ready to play this night at Peanut’s Pub, where they pass the hat. We were feeling blue, and we started singing gospel songs. Eva, Furry’s neighbor, a beautiful woman and a great cook, sang in fine harmony, “Will the Circus Be Unbroken.” We sang “Wasn’t that a Mighty Time (When Stones Struck Brinkley Town),” “Holy Spirit, Don’t You Leave Me” and “Happy Just to Be Here” until we were.

Furry was coming back from the bathroom (we might have had a drink of two) when he stopped and, standing in the middle of the floor, said “I wish that sometime I could make a whole album of gospel songs, a whole Christian album, but the people fuck you so bad.”

DISSOLVE to Nashville, where Furry is making the movie. Another friend is with him. I did not go along because I knew that if I went there would be fettucine all over the walls and because 20th Century-Fox wouldn’t pay me what I asked, though they offered to pay cash to save me tax money. On the Memphis home front, I have lectured Hornblower that one should never give a poet less than fifty dollars, at least twice that if the poet is passing the money on to a master. But some people refuse to listen.

“He was doin’ us a favor,” Burt Reynolds, speaking of Furry, told the Memphis Press-Scimitar when the filming was done, “and I think a lot of people on the other side of the camera didn’t realize that, and it made me very angry.

“He’s a legend. He’s the last of a dying breed, unfortunately, and I thought that he should have been treated like John Barrymore, and I did everything I could to see that he was treated that way. It wasn’t always easy because there were some people who thought that he was just a drunk old man. He’s not. He’s really an incredible human being. I would like to have his philosophy - life, love, music, everything. He’s very special.”

“I think we all learned something from Furry,” one of the other actors said.

“Yes, he did,” Reynolds said. “Everybody but the director.”

At one point Avildsen had told Furry there must be no more drinking on the set, and the next morning Reynolds presented Furry a magnum of bourbon. To have missed all this was a pleasure, but a guilty one.

After I knew Furry was back home, I didn’t go to see him. He had been paid for the movie, it was better than passing the hat, but introducing Furry to people who don’t respect him is not my idea of doing God’s work, and God must feel the same way, because one night while I am still in my guilt avoiding Furry, I am riding on the Memphis-Arkansas Mississippi River bridge in a ‘47 Chevrolet that I did not know had appeared in W.W. and the Dixie Dancekings and, just past halfway across the bridge, the Chevrolet sputters, dies, starts again and I hear that high diesel whine, look over my left shoulder and there he is, a tractor-trailer red flash followed by the wham of God, going faster not straight ahead but folding to the right and “Better get out of this thing,” I say, as the car is turning over, windshield cracking inward, roof bending and I see the outside rail of the bridge and know that whatever happens up here will be better than being down there - and then as if in a dream I am walking barefoot across broken glass under the light of U.S. 40 over the Mississippi River thinking a miracle has happened, I been in this bad car wreck and wasn’t even scratched, reaching up to wipe something wet from my forehead, noticing that I am wet and red all over, and starting out on a ride that leads to a doctor and a big bottle of codeine.

Later (the stitches were out, and I had learned that the wrecked car was in W.W. and the D.D.), I called 20th Century-Fox’s man in Memphis for an invitation to the preview, because I wanted to see for myself why God was so angry about it. I told the man I planned to write a review.

“Is it gon’ be derogatory to my picture?” he asked. I told him I couldn’t know for sure without seeing it. So at nine o’clock one morning I am in the southern part of downtown Memphis, past Beale Street, among the warehouses, at a screening room, watching Tom Rickman’s funny, honest, little story transformed into illogical, meaningless crap. Furry, whose character is pivotal - the band’s encounter with him must change them from scared kids to real musicians - is almost completely wasted. There is on the soundtrack one marvelous line from Furry’s special version of “No Place Like Home”:

Our Father Who art in Heaven Hallowed be Thy name This earth and my glory They may be the same

Except for that, there is no Furry Lewis in this movie, nor any 1957, in spite of its old songs and old cars (I saw the ‘47 Chev once, turning left). W.W. and the Dixie Dancekings did not set out to surpass Citizen Kane, but its aspirations were decent and intelligent, and there was a chance for a small show-business classic with a cast of musical southern non-actors and a man who has sold patent medicine off wagons and knows songs that were old on the plantations.

People holler mercy, don’t know what mercy means - Furry’s words came to mind as, leaving the preview, I drove past vanished blocks, where Furry and men like him had played and W.C. Handy had listened and Martin Luther King had marched his last, big flat squares where only the curbs remain, encircling gray primeval mud. Furry lived in one of those blocks when I met him. Some of his old neighbors have since been hacked up by medical students and buried in three-foot boxes.

I thought about the things that had happened over the past months - in Nashville with the denim and turquoise, in Memphis with Hornblower and Ginsberg, on the bridge with the big truck, and now the movie, in which Furry is all but invisible. The only good I could find in it all was the day that we sang the gospel songs, and it occurred to me that if I could get enough money from Rolling Stone to pay a master for two recording sessions, plus cutting costs and refreshments, we can make out of this mess Furry’s Christian album, no matter how bad the people try to fuck us. We will record it and press it on Furry Lewis Records, and all the money will be Furry’s. If we have to sell it off a wagon, Furry knows how to do that. He’s done it before.

Stanley Booth is the author of The True Adventures of the Rolling Stones, as well as Rythm Oil: A Journey Through the Music of the American South. His work has appeared in Esquire, Playboy, Newsweek, Granta, The Saturday Evening Post, and Rolling Stone. His latest collection, Red Hot and Blue: Fifty Years of Writing About Music, Memphis, and Motherf**kers was published by Chicago Review Press in May 2019.

He lives in Memphis, Tennessee.