ONE. Out here in Oklahoma, on the southern plains, the noonday sun is dazzling, annihilating, inscrutable in its immensity. Light convulsed from illimitable fire, it’s a glimpse, adorning the eyes, of the Lord’s own garments, a glory from which one can only beg, as did Peter atop Mount Tabor, to be sheltered.

“The sun is at home on the plains,” N. Scott Momaday wrote, “Precisely there does it have the certain character of a god.”

We’ve been in Oklahoma seven years, my wife and children and I, in an old house with black widows and fiddlebacks haunting its peripheries, a clutch of palm-sized wolf spiders underneath the cellar stairs. Stray cats wander the yard, and stray dogs slipped loose from their chains. Across the street an old woman in a blood-red housecoat sits in a chair on her porch most afternoons, smoking cigarettes and scrolling through her phone.

Flyover country, it’s called. Each day we look up at those jets stitching back and forth across the sky, sometimes four or five at a time, braving the realm of the terrible sun, bound for elsewhere, bound for the coast, trailing cloud.

Shortly after we arrived there appeared in our neighborhood a young woman we called the Witch Lady, shuffling down the street in an ill-fitted t-shirt and pajama pants, giggling, muttering, whirling her arms and sculpting in the air with her hands arcane, indecipherable shapes, as though casting spells at the broken trees lining the road — the maple, the hackberry, the Bradford pear. Casting spells — hence the name.

Where she came from, where she stayed, we never knew, but one morning we saw her cross into the park across the street from the house. As we watched with cups of coffee through the front window we saw her lay herself down in the grass, carefully, facedown with her arms at her sides, stiff and straight, near the edge of the empty basketball court.

A minute or two later a passing pickup truck slammed its brakes and stopped. A man jumped from the truck and ran to her, thinking she must be in distress or worse — Oklahomans in the main are friendly and kind, always willing to help — but as he reached her she leapt to her feet and he stumbled backward, startled and confused.

She gave him a dark, disgusted look, then scurried out of the park and down the alleyway behind the Seventh Day Adventist Church. The Samaritan stood there a few moments more, unsure of what had happened, the teaching in the parable somehow obscured. He got back into his truck and drove away.

Out here in the middle, the broken heartland, red dirt and dust — what Norman Mailer once bluntly named, in what seemed a simpler time, “those flat lands of compromise and mediocre self-expression.”

Oklahoma is a curious place. Peculiar, because even from its outset characterized by afterthought, indirection, implication. A territory forced upon the eastern Indians — Tocqueville himself saw the Choctaw crossing the Mississippi at Memphis, in wintertime, headed west — that new homeland then begun to bend and break under the steady pressure of outside events, the building and becoming of other places: Texas, Kansas, Arkansas… in the drawing of their boundaries, their light from dark, their waters from dry land, offering together a space between, a space left waiting, as though Oklahoma were not itself the loaves and fishes multiplied in the hands of the Lord, to the wonderment of the crowd, but rather that basket of fragments gathered by His disciples after the miracle dispersed.

Then, in April 1889, the first land run, the crowds pouring south across the Cherokee Strip, to devour even these fragments.

And the West was won.

TWO. This isn’t our first journey to this part of the world. To flyover country, I mean.

Rachel and I married in the fall of 2001, a month after 9/11, and after the wedding, on honeymoon, left New England and drove west, toward the Grand Canyon, but with the country wide open and beckoning took a meandering route, abounding in flexuosities, a path of least resistance left by imperceptible weatherings of the continent.

We found ourselves, after some days on the road, in mountains at the eastern edge of Tennessee, hogback ridges maculate in autumn color. We camped beside a cold, clear stream running shallow in its bed and watched, late into the evening, elk herds step from the forest into the meadows of the bottomlands to graze.

The valley there seemed haunted, as though startled from its sleep, frightened to find itself swarmed with strangers instead of kin. Out among the trees were old empty houses abandoned decades before when the government seized the land. There was a church and a schoolhouse, and even a small cemetery built along the near-vertical incline of a hill, a spot unfit for farming, and so perfect for the dead — forgotten souls under fallen leaves.

After dark, Rachel sat in our tent writing poetry by lantern-light:

Stay by me when the melting comes And all the bones of yesterday Rightly shall be swept away. Touch my hand while Bulbs begin to breathe And flowers send their seeds soaring through the air. Earth turns over restless And soil pulses hope in green leaves, But I am pale as the one who died on Friday. The Sun hurts a sheltered heart, Fries it on some forgotten sidewalk. So what shall I say when they ask me from where I came— When they ask, “Are you awake?” And all I want is to close my eyes? Hold me when ice subsides to warmer times. When movement is heard in breath and song, Keep me while the Earth moves on, Exhales uncovered, For Saturday is waning, And I am terrified of this new life.

In my own notebook I had an outline for a first novel — a kind of epic, fantasy western — about a reporter, an American, trapped in Indochina toward the end of the Vietnam War. Shot through the heart, a restless spirit seeking dissolution, he’s forced to follow the Mekong River upstream to its source, accompanied by a retinue of native gods, hungry ghosts. I imagined B-52s, angelic, scattering payload across the six green jewels of the countryside, pillars of smoke and flame, the crumbling sapphire cities of the Cambodian mountains, and piles of human bone left along the road to Angkor.

The story came, initially, from a nightmare I had about the war, running, lost in the jungle, and all around I heard the enemy signaling back and forth with clanging pots and pans, whistles and gongs. I was being hunted. Suddenly, there was a house in front of me, its front wall destroyed, the roof collapsed. I ran inside and found a baby doll propped up on an old cane chair, the flesh tight and burnt, hairless, almost a skeleton. It stared at me with shining eyes, and I heard it whisper, sweetly, I am the Angel of Death… the Angel of Death is upon you.

I wrote it all out, but never got past the outline. Because I didn’t know a thing about war, not really. Not then and not now, either.

I should’ve been writing about nightmares.

After three days we left the mountains and drove on into Tennessee. Outside Memphis a small whirlwind broke across the interstate directly in front of us, bringing with it a torrent of rain and thunder so resounding it cut through the music on the radio. The driving was dangerous, approaching impossible, but after a few awful minutes the sky cleared and the city rose before us, draped in twilit rain, as if it were seen, like Oz, as cut from jewel and precious metal, instead of asphalt, concrete, and steel.

Late that evening, drinking in a not-so-crowded Beale Street bar, we watched a broad-hipped black woman dance slow guitar blues across an empty dance floor.

THREE. Dreams are the children of tumult, and so often unsettle — dreams of six white moths outside my kitchen window; of a dog with a cluster of spider’s eyes; of someone spooning brains from the skull of a baby, and the baby is smiling.

Before we left New England for good — long after our honeymoon, but long before we moved to Oklahoma — I had another dream, of troubling significance:

I dreamt I was back at my old high school, wandering outside the theatre before a show. Dreams of performance are often tied to this space, where I first learned the strange work of the stage, gathering its possibilities, its curses and graces. I was running late, but stopped to search the crowd for a cigarette, and when I finally bummed one from a stranger, before I could light up the cigarette broke apart in my hand, the tobacco scattering onto the ground — a first frustration.

I’ve come to expect this kind of failure in dreams even if in slumber I’m seldom lucid enough to anticipate the pattern. Performance, in its most practical sense, is about being prepared, being present, hitting the mark, poised in that certain expectant readiness necessary for play, whatever the specificity entails.

The anxiety, then, is in unpreparedness: the broken prop, the dropped line, the missed cue, and even a recurring scenario in which the very performance itself comes as a surprise — how could I not have known there was a show tonight? — like stopping by a church on a whim only to find myself just in time for my own wedding, and to a stranger.

But in this dream, mercifully, those customary humiliations were postponed. Instead, another possibility intruded.

Toward me and the crowd, from the east, low in the sky and silent, glided a massive flying machine, Jonah’s great fish or the early Christian ichthys sculpted in the web and flange and rivet of skyscraper steel, its caudal fin sweeping back and forth, driving the beast along its way. It was immense, stunning, overwhelming. Seeing it, my heart leapt, and all expectations of performance were instantly forgotten.

The fish coursed west and I followed — suddenly elsewhere, a further unfolding, on a broad and sweeping plain, a ruined landscape of rust and rank weeds. Up ahead, in evening light, a skyline, a cityscape, silhouetted on the horizon.

It was years, many years, before we traveled out here to the southern plains, on our way to a new home in Oklahoma, Rachel driving, the children restless in the back of the van, on I-20 west from Shreveport, and up ahead — immense, stunning, overwhelming — as though captured in its own slumber, that same city silhouette against the sky.

I don’t remember if I said anything aloud, in that moment of recognition. I suspect I didn’t. I suspect I kept it in my heart.

Somehow, I dreamt of Dallas.

FOUR. “A pilgrimage,” the writer Paul Elie noted, “is a journey undertaken in light of a story.” For Rachel and I, on honeymoon, married in the Church yet still years away from a regular practice of faith, we found ourselves dangerously unmoored, longing if not yet listening for that call which might give our life together some measure of intelligibility — pilgrims at heart perhaps, but come of age when all well-trodden pilgrim roads had fallen into disrepair and disrepute, arrowing instead toward empty, disused shrines from which the glory of Israel’s god had long since flown.

Children of decline, unwitting survivors of what we’d later learn is the most aborted generation in American history, we inherited only fragments, and the promise of desire. What part are we to play? we asked ourselves, And what are our lines? Surely they must be written down somewhere.

“People your age have too many choices,” my uncle told me before the wedding, “You have nothing forcing you in any one direction, nothing forcing you to choose. When I was your age, the choice was clear — I went to college because I didn’t want to go to Vietnam. You have to pick a direction on your own, find your way somehow. Good luck.”

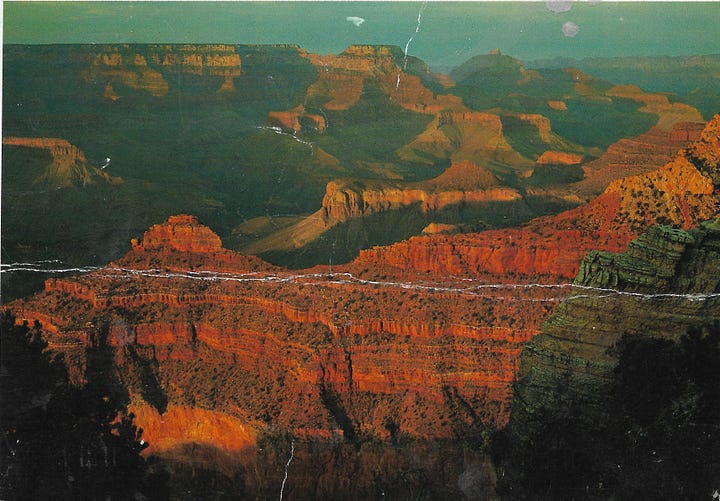

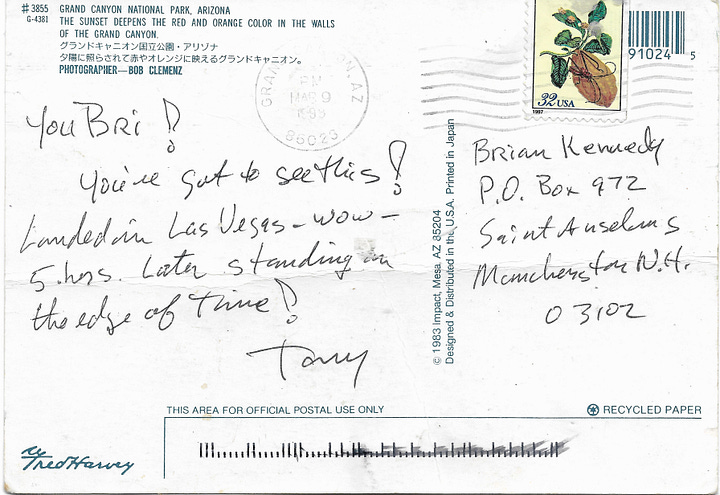

So we searched for signs to guide us. For our honeymoon, at least, it was my uncle again who gave us a way forward. He sent a postcard postmarked Grand Canyon, Arizona. On the front, ribboned walls of rock in a haze of rust-red sunset. On the back, he wrote: “You’ve got to see this! Landed in Las Vegas — wow — 5 hrs. later standing at the edge of Time!”

Before decamping from Memphis we stopped at Graceland, Elvis Presley’s mansion, on the front lawn of which his mother before she died kept chickens. The tour was guided by headphones, startlingly loud, which only underscored the peculiar obscenity of the place, the house itself seeming not so much a time capsule as a crashed alien artifact from an adjacent galaxy of nouveau riche peckerwoods.

I thought of the camel and the eye of the needle, and of poor, greasy Elvis himself, overweight, constipated, over-medicated, in his slippers, feeling slighted by the drift of the times but still Taking Care of Business, shuffling down the fully mirrored stairwell to his TV room, three television sets placed side by side, just like LBJ had his. On the coffee table crouched a white ceramic monkey statuette, its tail curled, its fingernails and toenails painted black, its perfectly round and staring obsidian eyes curiously gentle, wistful even, its hair swept back like a maître d’, and cradled in its paws what looked like a ball or a piece of fruit, or perhaps it was meant to represent that lost home world of the peckerwoods, and this their galaxy’s monkey god, passionless, contemplating some impending eschaton.

I said to my wife, “Take a picture of the monkey.” Only because my ears were overwhelmed by the narration, the trivia of the TV room, it came out as a bellow — “TAKE A PICTURE OF THE MONKEY! — and every person in that room turned to stare at me (who’s the peckerwood now, friend?) as Rachel, embarrassed, reached over and turned down the volume on my headset, the clearly marked controls for which I somehow overlooked.

From Memphis we traveled south on Highway 61, through the cotton country of the Delta, and camped in Rosedale, by the riverside. We met a stranger there, beside the Mississippi, who when we told him we were newly married, on our honeymoon, and wanted to be writers, gave us such a look of pity and concern it took us aback.

“If you’re out that way,” he said, kindly, when we mentioned our drive to Grand Canyon, “Go to Sedona.”

FIVE. Our first day on the plains, driving somewhere on I-35 north of Dallas, that city of encounter, that strange city of a dream, I fell asleep in the van alongside the children and woke up sometime later, north of the Red River, anxious and disoriented, opened my eyes and saw outside the windows the crumpled prairie and the endless, overwhelming sky.

I remember a moment years ago, praying after Mass, and through some subtle sense suddenly aware of Presence billowing from the tabernacle, almost roiling the air, offering itself without reserve into the world even as the world itself spun closer, what the Apostle called “the breadth and length and height and depth,” but in its movement and immensity not comforting, not reassuring, nothing so simple or self-serving — for the Gospel is not some vague palliative, it’s a man raised from the dead… and I tried to duck down behind the pew to get away from it.

I felt something like this in the van that day, our first day in Oklahoma, already startled by that recollected dream, that glimpse of Dallas, but now cowed by the immensity of the firmament, the Oklahoma sun and sky, that Presence… and me crumpled like the prairie into insignificance, wanting only to hide, to disappear, but afraid to move, stunned, a jack rabbit caught in the shadow of a hawk.

It happens here, I thought, It happens out here.

Do you understand? Some people won’t, some people in this land have emptied themselves of all expectation, of anything but appetite: “Leaning together / Headpiece filled with straw. Alas!”

But for you others with ears to hear — do you understand what I mean? I think I mean the end of that awful sense of waiting hanging over us, that’s hung over us now for decades… a nation of distraction and idleness… of sexual bulimia, endless war… celebrating monsters… and all of us haunted bodies wandering a haunted land, wondering if there really is any more ‘we’, or if it’s only you and me alone, us and them, a sense that things have spun out of control and are headed toward some inevitable confrontation, some necessary reckoning… as though America in our time has to offer not wealth or progress or sweet dreams of a better life but rather apocalypse, the veil grown thin, the gaze transfigured, the truth itself beheld with awful clarity, awful intensity, “like shining from shook foil.”

It’s not just decline I’m talking about, or end of empire. It’s not the price of groceries or the strength of the GDP. It’s something fundamental, something dire.

Last spring another young woman in our neighborhood — only twenty-four years old and pregnant with her second child — set fire to our neighbor’s garage.

When she was a little girl she began hearing voices, started seeing things that weren’t there. The voices told her she could fly, and her mother would often find her standing on the roof of their house, readying herself for ascension.

She had blackouts. She sometimes exhibited multiple personalities. She first entered a psychiatric hospital at age nine, then six more times by age nineteen. She didn’t finish high school. Her first job was at a strip club in Oklahoma City, serving drinks. She told the court “she quit due to the pressures to be an entertainer. She admitted she did try to be an entertainer because it was ‘just the top that came off.’ She stated it was good money but left her feeling degraded… she would drink tequila like crazy to get through her shifts… It is not something she would do again.”

She was first arrested for obstructing an officer, a criminal misdemeanor. “Guy in car,” she reported, “the driver, car stalled out and he took off, was only me in there. I was asked his name and said I didn’t know. The driver had been going 120 around the corners as he was running from the cops. I was getting a ride home, he saw the red and blue behind him and hit the gas. Cops were yelling at me asking me my name but I was shaken and glad to be alive. They were shining the flash light in my face, I was bawling… I got charged because I wouldn’t give the guy’s name. I didn’t know his name. I had seen him in the past, I didn’t know anything about this guy.”

“I will do what I got to do,” she said, “got myself into trouble.”

Several months later came the fire next door to our house. “I blew a car up,” she related, “All I remember, I was not intoxicated, it’s hard to explain… the father of my child, it was his car. I found he had slept with someone while I was in jail. He had given me a house key to this lady’s house… it was the home where it happened. I thought we were dating…”

The young man in question was arrested and jailed the day before on charges of drug possession and child endangerment.

“I don’t remember it,” she said, “but I did do it. I lit a bandana on fire, set fire to [his] car. It was in a detached garage of [a] house. I am glad it was not attached to the house. I took the key back to the house and apologized to [the lady living there]. She was just in the cross fire of who I was angry at, I was angry with him.”

I was outside that day, walking my dog. I heard this young woman screaming, saw a pillar of black, billowing smoke. She ran to me from the yard, asked me to call 9-1-1. She was shaking and crying.

“It’s gonna be okay,” I told her, “Don’t worry — it’s gonna be okay.” It’s all I could think to say. What more could I say?

And so the fire department arrived, and then the cops — the cops looking like they’d seen it all, but had rather they hadn’t — and a crowd gathered in the neighborhood. One man even sent up a drone, to film the scene from above. I walked away, wondering what happened, and how they’d make sense of it all. It was only later we learned she was arrested.

What failure. For her, certainly. For her children. But what burdens me more is the rest of us. The world — our nation, our people — has no real answer for this young woman’s dilemma, no balm of comfort for the pathos and confusion of her circumstances. Medication might keep her off the roof, the courts may allow for deferred sentencing or community service, social services might offer job training or counseling… and the Church, too, has programs, services, a calendar of sacraments…

And me, a Christian man with a good family and regular habits: “Don’t worry — it’s gonna be okay.” Which might be a normal thing to say, a nice thing, but doesn’t exactly qualify as evangelium, good news, gospel.

I thought of the women who gathered around the Lord, in the beginning. The lady companions of Jesus: Mary Magdalene; Martha and Mary, the sisters of Lazarus; Joanna and Susanna; the woman at the well; the woman with the jar of oil, for anointing.

In America in the 21st century we’re unable to offer any longer a compelling account of ourselves to the poor. Instead we medicate, we purge, we excuse, we endure. But we no longer answer — answer those whom Saint Vincent de Paul called “our masters and patrons.”

Because what that young woman needs, desperately, what we need, was what those other women witnessed, long ago — mighty deeds, and a Word of Power, efficacious:

Take up your pallet and walk…

Go your way, your sins are forgiven…

Let there be joy for those who love my cause…

But we’ve lost that necessary Word - lost is somehow along the way.

SIX. Words are necessary — especially for aspiring writers — but those we need the most ofttimes elude us.

Rachel told me that when she was a girl, she thought she saw an angel. She sat on the kitchen floor, playing with toys, alone, but grew restless, distracted, with an odd and unmistakable sense of something near, something she should be seeing but wasn’t, something right in front of her. She wanted to see, so she closed her eyes and opened them, closed and opened them again… until the scales shook loose somehow and there it was, an angel — or what a little girl thought an angel should be — fixed in the air above her. She doesn’t remember any wings. Its eyes were very kind. It didn’t say anything. It didn’t sing. She stared, overwhelmed, for as long as she could before she had to look away, and then only for an instant, but when she looked back it was gone.

Later on, she began to wonder if she really had seen anything at all. If she just wanted to see something, anything, and made the whole thing up.

Maybe she just didn’t want to think about what it would mean, really, to see something so — singular? Sublime? Terrifying? Crazy? Which was it?

She’s right, though — there is a clear difference between the limits of speech and a lie. Already in that fall of 2001, our wedding coeval with the march toward war, we heard the difference — between anguish desperately articulated, if clumsily, and on its heels the language of what Orwell called “swindles and perversions,” words like ‘freedom’ torn loose from native soil and used instead to garnish the prerogatives of empire.

The Church, too, in that season crept toward crisis, only months away from her Armageddon of Geoghans, Shanleys, and eventually McCarricks. But for a faith founded upon a revealed Word, and that Word made flesh, to note how completely, how scandalously, the Word’s Bride could be captured by the words of the world, of corporate liability and the fatuous marketing techniques of soda pop or toothpaste or sneaker advertisements was — breathtaking? Disquieting? Terrifying? Which was it?

Not simply in the Church’s handling of sexual abuse. Even in as principal a concern as the Eucharist, her teaching of the bread and wine at Mass become the very flesh and blood of God, the poetry is near now to being lost.

Our Catechism quotes the Second Vatican Council in calling the Eucharist “the source and summit of the Christian life.” That this phrasing be an almost pristine example of a mixed metaphor is hardly noticed. Mountains have summits, but not sources. Rivers have mouths. Which is it? It is many things, but certainly not well-wrought English. To think and speak in such a fashion, without a clear image in mind, is to think and speak in slogans alone — which is really to stop thinking altogether. “Every such phrase,” Orwell wrote “anaesthetizes a portion of one’s brain.” Is it any wonder then when the faithful cease to believe?

“Source and summit” is careless — committees rarely do better. Well-meant, yes, but consider that, along with the skulls of Jesuits and bishops, the road to hell is said to be paved with such intentions. We should instead recall those words offered to John the Revelator, on Patmos: Alpha and Omega. Beginning and End. First and Last. In these unmistakable antipodes the Christian life reveals itself as a journey in Word and Time, a journey marked in broken bread, and so in memory, a pilgrimage — through Natchez, Mississippi and Breaux Bridge, Louisiana, perhaps; through Houston, then Austin, to a house where an old pit bull and a one-eyed emu patrolled the yard.

“What you got to ask, y’know,” the man there told me, “is who wasn’t there that day? Who knew enough to stay home? There’s more to it than you or I’ll ever hear about, that’s for sure… Man, they can’t let people know the truth! Things are changin’, things are gonna change for sure… And of course I’d never say it to her face, but a woman’ll always be willing to give up a certain amount of freedom for security, that’s just nature…”

Waitresses gobbling diet pills at a breakfast diner in Fort Stockton; then El Paso, with the scandal of Juárez across the river; a night of food poisoning and other madness in Albuquerque.

Until finally, at the end of 4800 miles, standing stopped at the edge of Time, Grand Canyon, USA. Temple and pyramid, tower and sun — the shame of the earth laid bare.

That place is… silence, unmeasurable duration. Unspeakable. Some things just can’t — just shouldn’t — be said.

But we, the people? Forgive us, Father, we don’t know what to do. Faces crowded at the edge, grunts and groans and cackles and camera sounds, like the devils let loose from the Gerasene and chased into the greaseflesh filth of swine, run on and pushed out past the safety of the trees toward our ruin, but still no one able to follow through, the blue thread of the Colorado just too far down and gone, the leap now foolish, the chance passed.

We shouldn’t have been there. It didn’t seem right somehow.

We crept back to the edge after dark, when the crowds were gone, a mighty wind overflowing the canyon wall, spirit risen from the bedrock floor of time. They should hide that place from the likes of us, from all mankind. Cover up its nakedness, like Noah’s. Cover up its nakedness with angels’ wings. Or 4800 miles of perimeter wire, with orders to shoot on sight. Until the shame of it is lost to memory, let alone. Until the guardians themselves forget and fall. Then some starman come and crawl across the red rock to watch the Colorado make its final cut and flood the far side of the world.

Let someone else see that place. We stayed one night and drove away at dawn.

SEVEN. It’s not unique to Oklahoma, this flight from the poor, this fumbling for a Word. Pick a direction and go — to San Antonio; Memphis; Rapid City, South Dakota.

I drove eight hours west of here, to Santa Fe, named for the Holy Faith of Saint Francis in 1607. I met a man named Virgil, sitting alone in a doorway near the Cathedral downtown. He slept by the river, he told me, but only after dark. It’s safer then. His family — a daughter and her children — called him Pops. She took the children back to Missouri to keep them from their father — the man had become dangerous, crazed on methamphetamine. Pops planned on joining them in the fall, when the weather was cooler.

He did two years in the Navy in Vietnam, and still cried when remembering the war, especially what was done to the children. In 1979 he played a show at CBGB in New York with a punk band, Virgin Dog Meat — Pops played bass. He had DOA and MDC tattooed across the fingers of either hand — Dead On Arrival, Missouri Department of Corrections.

He was robbed recently, not for the first time, and wondered aloud at mankind’s puzzling capacity for cruelty — why steal from a man who has nothing?

“In Kentucky,” he said, “these kids come after me with a stick, four of ‘em in a group, started beatin’ me, left me layin’ there all bloody. Then they started laughing at me, ‘Look at that old man bleed!’”

A day later another man, Joey, outside an Allsup’s in Tucumcari. He sat beside the ice machine, smoking, confused, covered in flies, begged for change from me in mumbles, hardly trying.

He had LOVE and HATE tattooed across the fingers of either hand but never heard of The Night of the Hunter. “Is it good?” he asked me. America’s poetry inked into the hands of the poor, unknowing.

“Are you from here?” I asked.

He nodded his head.

“What’s it like?” All around were the ruins of the mother road, Route 66, a horde of tourists snapping photos of vintage signs.

“There’s nothin’ here,” he answered, “Nothin’ to do, there isn’t even a store, not even a Kmart.”

Farther down the road, inside a McDonald’s, a tiny, leather-faced woman pushing a wheeled wire shopping basket whispered to me, “He’s getting tiring.”

“Who’s getting tiring?” I asked politely. We stood near one another, getting ready to order. I tried not to notice her gaudy costume jewelry, her rings on every finger, her two prosthetic legs.

“The ghost outside,” she said, “The mouth outside. It’s been too many years.”

EIGHT. Because we remembered what that stranger in Mississippi told us, we left the Grand Canyon and drove south to Sedona. He was right — it looked like a car commercial. We got a hotel, drank beer, argued, and didn’t go outside. Our journey had stalled. Our pilgrim appetite had soured, and we were left alone, the two of us, to scrounge for some more palatable morsel.

Rachel and I married in the Church, that fall of 2001, but after the wedding waited years before returning to the altar, hearts and bellies hungry for the broken bread. In many respects we thought we were gone for good. There were many excuses to be made. It was and is an age of disbelief. It was easy to walk away.

We weren’t alone. The numbers are grim — for every one person now who enters the Church, six depart, the advent of a so-called secular age in which, to paraphrase the philosopher Charles Taylor, belief and unbelief present themselves as equally valid for you or me or anyone. A post-Christian society, as though the weary West might say, like Paul, “when I became a man, I put away childish things.”

Yet favoring this quasi-neutral language of a plural culture, geared toward winsomeness and relevance in the public square rather than gospel, obscures rather than clarifies our position. In an age of swindles and perversions, ‘post-Christian’ might be the mightiest swindle of them all.

What could be beyond Omega? Beyond the End or the Last? Have we not instead allowed the Enemy to confuse us? To tempt us? With words?

The Apostle Paul, in his correspondence with the Thessalonians, warned against any expectation of the Lord’s return “unless the apostasy comes first and the lawless one is revealed…” — Antichrist, “the one whose coming springs from the power of Satan in every mighty deed and in signs and wonders that lie…”

No man knows the hour nor the day, and many earlier ages argued the end was near, enthusiastically. My aim is not to suggest a looming Parousia. But if, as all our tradition attests, the advent of Antichrist be preceded by a great apostasy, a great falling away from the faith, would not our age be a fitting prospect? And wouldn’t a refusal to call our apostasy by its name not have a certain significance? Post-Christian, indeed.

Such language steals from us — steals from the birthright gifted to us at baptism. For whether the Lord returns today, tomorrow, or in another thousand years, the Christian life demands we discern in our own time both the shadow of things that were and a shadow of things to come, to suffer the mystery of lawlessness already at work, but also the mysteries of grace, until comes that final falling away — perhaps our own, perhaps another — after which God’s angels gather all the chaff of time for the fire.

NINE. We’ve been out here on the southern plains seven years now, my wife and children and I. This used to be the frontier, “the outer edge of the wave — the meeting point between savagery and civilization.” We’ve grown wary of those words. Civilization carried with it the Sword and the Cross, and the tension between those two missionaries of the West defined our past. I suspect they’ll define our future as well, despite our best efforts to leave them both behind.

“We stand today,” John F. Kennedy once declared before his party, “on the edge of a New Frontier… the frontier of unknown opportunities and perils, the frontier of unfilled hopes and unfilled threats.” Kennedy met his end, of course, some years later, in Dallas, that city of encounter, that strange city of a dream.

There was something else at the end of that dream — that after following a great steel fish toward the city on the plain, I suddenly found myself back again at my old high school, back to getting ready for a show. I was in a classroom, and the desks were piled high to the ceiling with clean white shirts. I went through the pile, frantic, trying to find a shirt that fit, a costume that might define my role. How could I not have known there was a show tonight? What part am I to play? And what are my lines? Surely I must have learned my lines. Surely they must be written down somewhere.

And so I searched the shirts, and waited to take the stage. Waited for words, words sweet as honey in the mouth. Waited, remembering Dallas.

It happens here, I told you, It happens out here. Flyover country. The broken heartland. I thought I meant the end of that awful sense of waiting hanging over us — but perhaps that sense of waiting, that expectation, is the very point. Perhaps we have to learn again to embrace that waiting for what it is — a cry toward Heaven, a cry for the poor, a Word longing to be made known:

Come, Lord Jesus

The poor deserve delight.

I did finally get back down to Texas, once upon a time. I sat one afternoon on a city street at an outside table with a cup of coffee, writing in my notebook. Above me, that unendurable sun of the southern plains. At some point, a disheveled young man stalked toward me from across the street, his muscles twitching, his body drenched in sweat. He pulled up a chair and sat down.

“What did you just write? Tell me.”

I paused, wary, then read from my notebook: “It’s not that the rich man is unloved by God — it’s only that it’s hard to see the rich man through his riches, just as it’s hard to see the poor man through his rags.”

“I like that,” he said, intensely. He seemed in every moment as though trying not to scream. “I don’t agree with it, but I like the poetry. Let me tell you a story — I want to write it down in your book. Will you let me?”

I nodded and passed him the notebook. He began to write, speaking aloud as he did, haltingly, a man’s voice but a child’s cadence:

“There once was a dog. The dog was in a cage. The cage was outside. One day, it started to rain. Some people could see the dog in the cage outside. In the rain. And it started to pour. And someone felt bad for the dog — they brought the dog some food. And someone else felt bad for the dog — they brought some water. And someone else felt bad for the dog — they brought a blanket. But it was still in a cage. And it was still raining.”

He grew agitated.

“I can’t do this — you need to write it — you need to write this down. WRITE THIS DOWN!”

I grabbed the notebook and pen and wrote quickly, trying to keep up with the flow of words.

“MY NAME IS YOU-ARE-BLESSED! THE FACTS ARE THAT THIS JUST HAPPENED! HOW MANY TIMES HAS THIS COME TO PASS? WHERE WERE YOU WHEN I WAS DYING? DO YOU NEED A PAIR OF SHOES?”

He paused, spent. He reached into his pocket and dumped a handful of change — pennies, nickels, dimes — onto the table.

“That’s all I have in the world, right there.”

We both stared at the coins.

“How many days in your life have you spent in poverty?” he asked.

“None,” I answered, honestly.

“I hate you for that,” he said.

We sat together a moment, staring at one another, silent.

“I can show it to you,” he said, “if that’s what you want. You can see it for yourself.”

“What’s that?” I asked.

“The truth of it. Just come hang out with the homeless guys, that’s all. There’s no harm. We got beer, cigarettes.”

I shook my head. “I can’t do that.”

Without a word, he grabbed his coins, stood up, and walked off into the street. I watched him go, watched him stop to bellow at a passing highway patrolman, teeth bared, watched him stop to beg from another man at a gas station on the fire side of the street.

Soon after, I returned to my hotel for an afternoon nap in soft, clean sheets. Someone held the door for me as I entered. Someone called me “sir.”

TEN. Rachel and I stayed two nights in Sedona before heading back east. We drove all day, the car packed full of everything we owned — blankets and boxes and tapes and books, suitcases and CDs. Camping gear, my guitar, the map. We found the campground after dark, out in the desert off Texas State Highway 17, south of the interstate, ten hours east of Sedona on the roads. Balmorhea, it was called. We stopped knowing it was only a six-hour drive into Austin come morning.

We pitched our tent away from other campers, as always… didn’t even bother cooking dinner… just slept… sleep mixed with sounds in the night — footsteps in the gravel, laughter, engines and animals growling in darkness.

We kept that way through all that happened, even as the wind rose, even as the tent started to move, started to buckle and sway, we never woke up, not really, even when the walls collapsed in and down, brushed against our faces… and when, half-asleep, we reached out to force the walls back into place it felt like hands out there on the other side pushing back, playing with us, trying to figure us out. Trying to find us.

But still, we didn’t wake up — strange, isn’t it? We can ignore so much when we need to.

In the morning we didn’t say a word, just broke down the gear, packed up the car, and got back on the road.

Finally, an hour or more down the interstate, Rachel asked, “What happened to us back there? What was that? What happened?”

I thought of our first night out together, she and I, so long ago, back east, when we fell in love sitting atop a great rock cliff on the western edge of a nowhere American city, the rock covered in graffiti and trash and busted glass… and from up there we could see the buildings and streets laid out in tight grids beneath us, and the church steeples reaching through the dark sky, toward a ceiling of stars. Because the night was autumn cold we sat close to one another, limbs tangled, until suddenly there we were, she and I, holding hands, beginning.

What happened to us back there?

I don’t know… an angel maybe. A dream. Or a ghost. I don’t know as we’ll ever know for certain. I can only tell you what I remember.

Brian Kennedy is the founder of Lydwine, as well as the frontman and principal songwriter of the arthouse country band The Cimarron Kings. He lives with his wife and six children in Guthrie, Oklahoma.

Notes. Oklahoma’s own N. Scott Momaday quoted from his novel House Made of Dawn (Harper & Row, 1968) - Norman Mailer’s essay “Superman Comes to the Supermarket” was first published in Esquire in November 1960 (as “Superman Comes to the Supermart”) and is anthologized in the remarkably entertaining Smiling Through the Apocalypse: Esquire’s History of the Sixties (Esquire Press, 1987) - Alexis de Tocqueville’s eyewitness account of the Choctaw enduring their forced removal to Indian Territory is in Book One, Part Two, Chapter Ten of Democracy in America, in the section translated by George Lawrence (Harper & Row, 1966) as “The Present State and the Probable Future of the Indian Tribes Inhabiting the Territory of the Union” - Rachel Kennedy’s poem “Easter Vigil” reprinted here by permission of the author - Paul Elie quoted from The Life You Save May Be Your Own: An American Pilgrimage (Farrar, Strauss & Giroux, 2004) - That the thirteenth generation since the American founding (called 13ers, or Generation X) is the most aborted generation in American history is taken from Generations: The History of America’s Future, 1584-2069 by William Strauss and Neil Howe, which bears quoting in full: “Through the birth years of the last-wave 13ers, would be mothers aborted one fetus in three.” - Observation that Gladys Presley kept chickens on the front lawn of Graceland is from our friend Stanley Booth’s reportage “A Hound Dog to the Manor Born” published in the February 1968 issue of Esquire - In case you can’t make it to Graceland, Elvis Presley’s monkey was photographed for posterity by William Eggleston in 1983 - Saint Paul wrote of “the breadth and length and height and depth” in Ephesians 3:18 - T.S. Eliot quoted from “The Hollow Men”, first published in his Poems: 1909-1925 (Faber & Dwyer, 1925) - Gerard Manley Hopkins quoted from “God’s Grandeur”, a poem written in 1877 but not published until 1918, thirty years after the poet’s death - Details regarding the strange fate of our neighbor’s garage are in the filings of the District Court in and for Logan County, Oklahoma - “We must serve the poor,” Saint Vincent de Paul wrote, as included in the Office of Readings in the Liturgy of the Hours for his feast day each September 27th, “especially outcasts and beggars. They have been given to us as our masters and patrons.” - Words of Power are from John 5:8, John 8:11, and Psalm 35:27 - George Orwell quoted from his 1946 essay “Politics and the English Language” - The Catechism of the Catholic Church (United States Catholic Conference, 2000) offers the Eucharist as “source and summit of the Christian life” in paragraph 1324, drawing directly from Lumen Gentium, the Dogmatic Constitution on the Church promulgated by Pope Paul VI in November 1963. Paragraph 11 of Lumen Gentium in its original Latin reads “…totius vitae christianae fontem et culmen…”, sometimes translated as “source and summit” and sometimes as “fount and apex”, both of which mix metaphor, though the former shows clearly the mysterious power of alliteration to cloud men’s minds, at least in English - That only half of American Catholics understand (and only one-third believe) the Church’s teachings regarding the transubstantiation of the Eucharist is from a report by the Pew Research Center, July 23, 2019, “What Americans Know About Religion” - John’s antipodes are in Revelation 22:13 - The exorcism of the Gerasene (or Gadarene) demoniac is recounted in Matthew 8:28-34, Mark 5:1-20, and Luke 8:26-39 - Regarding Pops' tattooed knuckles, an astute observer points out that DOA and MDC (Millions of Dead Cops) were both well-known hardcore bands of the era, which Pops probably knew if he was the type to play at CBGB. Though Pops did specify that MDC was meant to indicate the Missouri Dept. of Corrections, it just goes to show that meaning is ofttimes stacked upon meaning in this well-wrought world of ours - "For every one person joining our church today, 6.45 are leaving" was a sobering statistic offered by Bishop Robert Barron in an address to the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops in 2019 - Charles Taylor paraphrased from A Secular Age (Belknap Press, 2018) - Saint Paul wrote of “childish things” in 1 Corinthians 13:11, and discussed apostasy and Antichrist in 2 Thessalonians 2:3, 9 - Revelation 22:20 pretty much sums it up - Quote regarding the savagery and civilization of the frontier is from Frederick Jackson Turner’s 1893 essay “The Significance of the Frontier in American History” - “We stand today on the edge of a New Frontier…” is from John F. Kennedy’s acceptance speech at the 1960 Democratic National Convention, in Los Angeles, California, the phrase coined by Kennedy advisor Walt Whitman Rostow.

I came over to read this and subscribe on a recommendation from Mark Bisone. I thank him for steering me this way and I thank you for an intriguing and beautifully written story featuring prominently my home state of Oklahoma. I thoroughly enjoy knowing that you chose OK as your home for you and your family. The redlands and mesquite, the open flat plains of the panhandle, and the many homespun people who populate her rural regions are close to my heart. I've lived in Texas and Kansas and Illinois since leaving Oklahoma upon adulthood, but it will always be the place I call home.

Beautiful