Feast of Booths, Part Two

Broken Hearts to Celebrate

— READ PART ONE OF FEAST OF BOOTHS —

“The value is not in the suffering, but in the soul’s desire.”

- Saint Catherine of Siena

ONE. After Stanley Booth became a Catholic, received into the Church at Easter Vigil 1993, he went home and cried all night, then got up and went to Mass again in the morning. He was back in Georgia then, settled near his parents and his daughter, in a house with a pool, with a mirror over his bed. For nearly a decade — away from Memphis, the Stones book finally complete — he’d been living, by his own account, in a “period of freefall.. near lethal.” That he be able even to distinguish somehow this time of ruin from others was itself a special grace, given the many miseries he’d managed to endure in the years since 1969, since the blood and mayhem of Altamont — the deaths, depressions, accidents, addictions, arrests, sordid affairs, and failures. “The marriage ended,” he later wrote, memorably recounting one such instance, “when I set her car on fire.”

Stanley gave up on ruin eventually — failing, he realized, in even his best efforts at failure. “I had just fucked up so much,” he said, “that I just took myself to the Church and turned myself in.” Perhaps, like Jacob, he was finally able to wrestle his angel to a draw, and as his stubborn blessing receive that “flash of lightning from without” Fulton Sheen wrote of to describe conversion. As a boy, growing up in Waycross, Stanley would watch Sheen’s television program, Life is Worth Living, broadcast weekly on the DuMont network, thrilled by the bishop’s erudition and style. As he matured, he read Waugh and O’Connor and the rest, and even at his most dissolute could often be found — at St. Louis Cathedral in New Orleans, for instance, or Ss. Peter and Paul in San Francisco — haunting the racks of votive candles at the front of a church, close to Christ in the broken bread. He always wanted to be Catholic, he told me. “I just didn’t think I was going to be able to get from where I was to the Church in one lifetime.” In the end, the first step was hardest. “Everything else,” he said, “was easy.”

The pastor at his parish in Georgia — St. William’s, on St. Simon’s Island, no less - was an elderly priest who’d begun his seminary training as a teenager, and had already given nearly seven decades of service to the Church. When it came time one evening for Stanley and the other candidates and catechumens in the Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults to make their first confessions — the Sacrament of Reconciliation, we call it now — the priest was nowhere to be found. One of the men in the group walked over to the rectory and found the old man asleep in front of the television. Roused from his much-deserved slumber and brought back to the church (built down the road from the site of the original Franciscan mission of the sixteenth century, where the friars were martyred by the local Indians) he found Stanley — first in line, of course — waiting in the confessional.

“Father, I’m fifty years old,” Stanley told him hurriedly, “There are people behind me. There’s not enough time to tell you all my sins.”

“What?” the old priest squawked — then, perhaps weighing the practicalities: “What were you?”

“Well, my mother and father were Methodists… Father, I lived like an animal.”

But the priest, having seen too much of humankind, was unimpressed, and sent him away, shriven, with a mere handful of prayers as penance, the dark work of a lifetime quickly undone.

Nevertheless, a wonder, truly — from the broken depths, to give oneself to God and be reconciled, so simply and so sweetly, so fully. “The tragedy of the life of Judas,” Sheen wrote, “is that he might have been St. Judas… There is a world of difference between pounding a breast in self-disgust and pounding it with the mea culpa in which one asks for pardon.”

Penance, and then at Easter Vigil received at last with flesh and blood from the Lord’s table, with open arms, in thanksgiving. This is no small thing — in the joys of initiation the heavens are redrawn indelibly. But the Christian life is seldom happy-ever-after, and surely something more than the dénouement of conversion. Evening comes and morning follows, as it has since creation. Life goes on.

Stanley taught Catechism to seventh graders, which was, he recounted, “about as unrewarding a thing as I’ve ever tried to do.” He tried very hard, very earnestly. “No shouting,” he told them, “raise hands if you want to speak… No shouting. No exceptions even in case of fire… I have much good news to give you, if you’ll listen.” He read to them from Hopkins and Cormac McCarthy. He brought in Socrates, Simone Weil, Hank Williams, and the blues. He shared with them a homemade history of the universe from the Big Bang through the deaths of Buddy Bolden and Bix Beiderbecke in 1931. He found the kids whose parents were most involved in the Church were often those who were most uninterested:

“My job is to teach you. In the past I have taught karate, and if I were teaching you karate I could teach you Catholicism or anything else more easily, because I could command your attention… I’d like to do three things before Easter — teach you the sacraments, study the liturgies of the Word and the Eucharist, and enjoy some of the great Catholic writers that made me a Catholic. We can’t do that if you’re acting like inmates in an asylum, tearing paper, taking off your shoes, throwing things, hitting each other. So far this hasn’t been altogether a pleasure for me. Let’s relax, take a deep breath. We’ll be here for the next hour. If we concentrate, it will pass quickly and pleasantly. If not, not.”

“I was so fucking sincere,” he told me, “I was so fucking in love with the Church. I was so with the program, I would’ve been crucified… but those kids, they were only interested in masturbating, and golf.”

Because even with another Mass to go to, whether on Easter morning or an ordinary Sunday, faith is a gift — Stanley’s tears are proof enough for that. Overshadowed by God, we are not undone. The scars of sin remain and bleed — cleansed, yes, but never fully healed. We suffer for the memory of the past, even though the guilt of it be forgiven or forgotten. We struggle to accuse ourselves in the present. We endure the frailty of others. We wait in hope.

As Sylvia Plath wrote, only days before she died, “Once one has seen God, what is the remedy?”

TWO. “One of the chapters of the Stones book,” Stanley told me, “I was pretty… whatever I was at the time. I remember I’d come back to Memphis, I had this big holder for legal pads, long 8½ x 14 legal pads and I had all the notes for this chapter I was gonna write… and I opened the pad and there it was. I’d already written it. That was, like, scary — but good. That’s really a true story. I didn’t recall having written that, but there it was.”

I sat in Stanley’s living room on the burgundy chaise lounge, underneath the two framed portraits of Lash LaRue, his boyhood idol. Stanley sat on the couch, or in his wheelchair, with a low wooden shower stool set beside him as a makeshift end table, cluttered with loose papers, loose change, lighters, pens, remote controls, reading glasses, a Barlow knife, his allergy pills, rolls of antacid, and seasoning for his ramen. The television played cable news, or a classic movie channel. “People don’t realize what a good man Bob Hope was.” Books piled everywhere, of course — on shelves, on the tables and the carpet, on the couch and chairs, in the bathrooms, books stacked in boxes, and with them boxes of records, photographs, magazines, manuscripts, and other ephemera. Hot Shot Roach Killing Powder spritzed here and there on the floor. An Elvis Presley trash can and — stood beside a coat rack and a western saddle near the back door — a life-sized cardboard cut-out of Roy Rogers, smiling, pistols drawn.

“[William S.] Burroughs told me how to do it. He said… well, I can’t repeat everything he said because I can’t remember everything. He said, ‘Arrangement is going to be your problem.’ That meant a great deal to me. It’s not specific, but… arrangement. I thought, yeah, drama is contrast, drama is conflict… let’s have as much humor as we can possibly milk out of this fucking dry gourd, to balance the nightmare that is coming.”

Occasionally, embarrassed and tongue-tied, I’d scrabble at my notes for one of the questions I’d prepared — about music and literature in an age of mannerists and minor poets; about Memphis succumbing, for the sake of tourist dollars, to ever more vulgar forms of spiritual and historical blackface; about the Rolling Stones having abandoned the moral arc of their music, that arc of sin and redemption, in favor of foolishness and celebrity.

“I don’t find them absurd… No one is always at their best… and Ronnie is a fantastic musician, though I admit it’s hard to imagine him ever playing something that’d make someone cry…”

I soon realized most of my questions weren’t really questions at all, but rather conclusions in search of affirmation, and that I’d come to Memphis, in no small measure, to speak with Stanley “as if he were a prophet, and I were a pilgrim seeking revelation.” This disappointed me. I was treating him as everyone did, and as I swore I wouldn’t — as a sort of third-class relic, as someone who’d touched the mystery and lived: Stanley at Stax with Otis Redding; Stanley at Graceland or Elvis’s ranch; Stanley at Dick Carter’s Altamont Speedway, in the glare of the lights, watching the Hells Angels rend and roam.

“I am finding manuscript pages, and that’s good. I just want to find all the manuscript pages I can because I think I probably was better then than I can be now, and maybe that’s not true but I still want to find all the pages I can before I get…”

Many years ago, three-quarters drunk and boasting, with a hyperbole he would later regret, Stanley told a pair of unimpressed English visitors, “Memphis, Tennessee, has changed the lives of more people than any other city in the world,” and noted that people everywhere had “shopped at supermarkets, eaten at drive-in restaurants, slept in Holiday Inns, and heard the blues because people in Memphis had found ways to convert these things into groceries.” He first came to Memphis in September 1959, aged seventeen. “I thought they were Yankees,” he told me, “they talked funny.” His father, who sold insurance, had accepted a position with the Lincoln American Insurance Company, first called Columbia Mutual but rebranded in hopes that blacks would favor a company named for the Great Emancipator.

“I knew little about the place,” he wrote, “other than that it was on the Mississippi River and had an association with the music I liked.”

At Memphis State, under the tutelage of Walter Smith, Stanley read Wagenknecht’s Cavalcade of the English Novel, and worked his way through Richardson, Smollet, Carlyle, Swift, Sterne, Fielding, Austen, and Forster, among others. An acolyte of Ernest Hemingway, he met that man’s suicide in 1961 with the thoroughgoing seriousness of late adolescence, troubled by “the knowledge that Papa was no longer going to be around to live the exciting, heroic parts of our lives for us… there was no one to take his place; no one save ourselves.” In response to the challenge, with an eye for detail and an ear for the music, Stanley soon immersed himself in the personalities of Memphis, the city’s half-mad grit. “I did everything with the express purpose of wanting to write about it,” he said, “When I found the blues, I found my métier.”

“I was in the eleventh grade, and we had to write little papers, and I wrote a paper about driving the family car around, the family sedan, and getting chased by the cops for speeding, and how I eluded the cops. It was just like, you know, a couple of pages, handwritten, but the class laughed, and I thought, ‘If I can make them laugh… who knows?’”

“The blues,” Stanley wrote, “speak in exalted language of dramatic situations. This is what Homer, Sophocles, Shakespeare, and Tarantino, among others, also do, in their various ways… Marlowe or McTell, it’s all poetry.” He saw within the tradition, not inaccurately, a force vital enough to gather Wordsworth and Coleridge alongside Hank Williams, and even Mick and Keith. But still his vision is somewhat overstated, or misapplied. Mathew Arnold notwithstanding, literature as such is not generative of culture, at least in the longue durée. For all its romantic poetry — the doom and loneliness of the haunted, hunted guitar-man, waiting at the crossroads, or the shack beyond the pines where the music swells and the hips grind — the blues as sensibility, as poetics, ultimately roots itself within a revelation of the living God, who separated light from darkness and the seas from dry land. Like much of American music it is from and for an apostolic people, those who have shaped their lives, however imperfectly, against a Word.

“I sing God’s music,” Mahalia Jackson famously said, “because it makes me feel free. It gives me hope. With the blues, when you finish, you still have the blues.” Though well-turned, her distinction is imprecise. If not God’s music, the blues at its best is surely an outcry of His people, even if only registered as grumbling in the desert, or tumult before a golden calf. The God of the whirlwind, of Abraham and Isaac, the God of the cross and the empty tomb, revealed Himself, in time, as God also of kidnapped Africans, freed slaves, sharecroppers, and their descendants, and that this witness be granted to both saints and sinners only underscores their common lot in the fidelity and shame of Israel. “Al Green speaks in tongues,” Stanley reminded me more than once, and it bears repeating to blues enthusiasts, often irreligious, that this is something more than local color. The Spirit is real and blows where it will. That old, weird America was and is vividly sacramental, and within it Milton’s Satan — or Robert Johnson’s, for that matter — is a being markedly different than any of Eliot’s hollow men.

“I was a child, no older than sixteen. I was in the Waycross Library and found this book, Plotting, by Jack Woodford, and he said if you want to write a book, start with one story in the first chapter, another story in the second chapter, and bring ‘em together in the end. Man, that was so simple even I could understand it. And that’s what I did. If you read the Stones book, that’s exactly what I did.”

“What sort of man reads Playboy?” that magazine asked in April 1970, “A man with a penchant for picking a winner — who lives life enthusiastically.” Presented in the same issue (alongside Miss April, a blonde from Milwaukee) was Stanley’s portrait of blues musician Furry Lewis. “People holler mercy,” Furry sang, “don’t know what mercy mean… Well, if it mean any good, Lord, have mercy on me.” As a young man Furry made a name for himself with the crowds on Beale Street, but his only steady work in the decades since had been as a street-sweeper for the City of Memphis Sanitation Department. Nearly forgotten in an age of rock and roll, he would often pawn his guitar for beer money.

Characterized by the magazine as a “nostalgic visit” and offered alongside advice and advertisement on sports cars, satin sheets, feminist tactics, pipe tobacco, and orgasm during pregnancy, it was, if only inadvertently, a study in comic contrast — the humility of the powerless set against the self-satisfaction of the modern gentleman, desperately adorned. “I agree with the Wichita couple who spoke in favor of mate swapping,” wrote an anonymous reader from Oak Ridge, Tennessee. That this be seen as progress — the devotees of a commercial age laying aside psalm and sign in favor of sexual hygiene, like Esau fouling his birthright — was at least in keeping with the spirit of the nation, our obsession, as Tocqueville observed, with the “indefinite perfectibility of man.” But something was lost in the ascent, perhaps irrevocably. Not that puerile romanticism equating suffering with inspiration — the 19th century housewife whose suicide she hoped would jumpstart her husband’s poetry. Call it instead a genuine affection for helplessness.

“Virtuosity in playing blues licks,” Stanley would later write, “is like virtuosity in celebrating the Mass, it is empty, it means nothing… a true blues player’s virtue lies in his acceptance of his life, a life for which he is only partly responsible.”

Herein is neither the penchant for picking a winner, nor enthusiasm, but the plainest recognition that even if suffering cannot be conquered it can be endured, and so transfigured — that even broken hearts are meant to celebrate. “Give out,” as Furry counseled, “but don’t give up.”

“Those early Sun records were brilliant, and then… When Colonel Parker came in the whole tone of the thing lowered, because Colonel — Colonel didn’t give a shit about music. He didn’t give a shit about Elvis. He gave a shit about money.”

Though published in Playboy in 1970, “Furry’s Blues” was written in 1966, at the start of Stanley’s career, and it was while trying unsuccessfully to place the piece in a national magazine that he caught his first real break — an assignment from Esquire to profile Elvis Presley, a fellow Memphian. A portrait of the artist in semi-retirement, “A Hound Dog to the Manor Born” ran in February 1968. Though acknowledging the undeniable impact of Elvis’s rise in the mid-‘50s, Stanley had the temerity (and local connections) to present a now grown-up Elvis in a less-than-favorable light — as frivolous, idle, castrated by his own success.

Fifty years later, Presley remains a focus of consternation, as the singer’s legacy in Memphis and the wider world, “idealized beyond measure,” still troubles Stanley deeply. “They’re still obsessed with Elvis,” he told me, exasperated, “They’re not obsessed with Furry, or Gus Cannon, or Bukka White.” Disappointed in the outsized attention paid to Elvis, Stanley seems equally dismayed with the man himself, who seemed content at nearly every turn to squander the force of his talent on schlock, schmaltz, and Pepsi. “It’s a seldom remembered fact,” Stanley wrote, “that Elvis recorded more songs by Ben Weisman, who wrote ‘Rock-a-Hula-Baby’ and ‘Do the Clam,’ than any other songwriter.”

Presley, perhaps overawed by his own good fortune, was content to let others lead his way. Favorite son that he was, he never lost those characteristic habits of poverty, both good and bad. “He was,” Stanley wrote, “for all his life, deeply ignorant and aware of it, living on cheeseburgers, BLTs, and fried peanut butter and banana sandwiches because he was afraid to order things he didn’t know how to eat.” Writing in Esquire, Stanley relayed an anecdote of Elvis, shortly after the death of his mother, “standing on the magnificent front steps of Graceland. ‘Look, Daddy,’ Elvis sobbed, pointing to the chickens his mother had kept on the lawn of the hundred-thousand-dollar mansion. ‘Mama won’t never feed them chickens no more.’” For those of us with more refined sensibilities, the scene is embarrassing. But though easy enough to caricature, easy to laugh at, easy to dismiss as trash, we forget that much of America, its best and worst, was built on such instincts — because trash has nothing to lose.

“What must Elvis have seen,” Stanley wondered, “looking into Gladys’s eyes?” This hillbilly prodigality, founded in desperation, is in keeping with the general tone of heritage in Memphis, oft-noted for a stubborn and habitual misappreciation of its own importance. “We don’t have any real culture in Memphis,” a lady Memphian told the writer David Cohn, some years between the fall of Beale Street and the advent of rock and roll, “We have culturine. You know, like oleo-margarine. Looks like butter but isn’t.” Or, as Stanley so succinctly put it, “there is something about Memphis that makes you want to get down on your knees and shoot dice.”

Consider that the city advertises itself, quite rightly, as Home of the Blues and Birthplace of Rock and Roll (even as this seems to imply a strained relationship between mother and daughter, as though the girl ran off, and never writes) yet also allows its city center to be dominated by a 321-foot-high pyramid, ninth largest in the world, adorned with the logos of Bass Pro Shops and Ducks Unlimited Waterfowling Heritage Center, and housing, among other attractions, “the world’s largest freestanding elevator,” a 103-room hotel, a pistol range, and “a nautical themed restaurant and bar with a saltwater aquarium and a 13-lane ocean-themed bowling alley” with shoes renting at $4.25, and socks at $3.50. So low-down vulgar, it’s a wonder Huck and Jim didn’t come ashore and start a record label.

But there is such a thing as trying too hard, and perhaps this very vulgarity has allowed Memphis to catch lightning in a bottle, time and again. What happened in the city is undeniable, even as it now seems so impossibly distant. It seemed so even in 1968. In December of that year (perhaps in response to the Esquire piece) Presley appeared on NBC for his justly celebrated Comeback Special, his first public performance in seven years. But even when he sang “That’s All Right” in the boxing ring with Scotty and the boys (the song that started it all, his first hit for Sun Records in 1954), dressed in black leather, his voice raw and uncompromising, it was still the voice of a man in his thirties, a man’s voice, with less than a decade to live, and something quite different from the voice of that nineteen-year-old truck driver come up from Tupelo — casual, greasy, almost womanly, somewhere between high lonesome and horny — when the world was new. Because life goes on. Evening comes and morning follows, as it has since creation — even in Memphis.

“Darvocet… He was big on his pills, he just give me a handful of ‘em. Dewey was not a pharmacist, you know? He advised me, since I’d been takin’ all this LSD and shit, that I better take a fistful. So I did, and then I started having double-vision and stuff. It was just funny, puttin’ my two cars between the four cars on the interstate… Elvis, you know, I think he always loved Dewey, but he realized Dewey was just too out of control.”

“It all happened pretty fast,” Stanley said. The success of his work with Esquire brought an invitation from The Saturday Evening Post to chronicle soul music in Memphis. “The writing business is all about lunch… I was meeting editors all over town.” Researching the piece, Stanley watched Otis Redding write and record “(Sittin’ On) The Dock of the Bay” at Stax, ‘Soulsville U.S.A.’, shortly before Redding and six others died in a plane crash, touring in Wisconsin. “If you got the feelin’,” Redding told him, “you can sing soul. You just sing from the heart, and — there’s no difference between nobody’s heart.”

“[The Post] really liked my Memphis sound piece,” Stanley recalled, “until they found that two of Booker T. & the M.G.’s were black and two were white, and then they decided to put Red Grooms’ papier-mâché model of Chicago on the cover. I thought, for a magazine published in the City of Brotherly Love, that’s pretty low.”

Left alone with the music, Stanley continued to discern, painstakingly, the contours of his own vocation. “And then Otis came on,” he scrawled in his notebook, late one night, listening, “so beautifully ready to give you not only himself, his body, his voice, his heart, but give you as well his soul — meaning something mysterious but real about making an agreement with the audience whereby they would love him if he would live for them and teach them how to play.”

“Such music,” he also noted, “…cannot be played by someone thinking about the instrument or anything except just what it was he wanted to hear next. One has to learn what to want.”

Preoccupied with his next steps throughout the period, he struggled to complete a profile of blues legend B.B. King for Eye, the Hearst Corporation’s bizarre and short-lived foray into the counterculture. “The only thing that matters is being a writer,” he noted in mid-July 1968, “learning how to write. Anyone who can state what matters so simply is probably an idiot… Writing an article for Eye about B.B. seemed so simple —but as always happens, as I’ve tried to write it, my ignorance of the subject, my complete inability to deal with it, has become evident. Of course, no one else has dealt with it, either, and I’m sure, even in my despair, that I will be the one to do it. But when?”

A few days later, he lamented: “I love B.B. and I really don’t know why the hell it’s so hard writing about him. Something about it is very hard — it’s just, probably, that I haven’t quite got through yet to the real tragedy that is there, in B.B.’s life as in the life of every great man. For one thing, I am forcing myself to write too quickly, not giving myself time to think. I have to live with a problem for a while.”

By end of summer, his work on the article finally complete, Eye asked him to follow up with a piece on Johnny Cash. Stanley convinced the editors to accept instead, and fatefully, a profile of “five English musicians who play nasty rock ‘n’ roll better than any band in the world” — the Rolling Stones.

“You know, everything is so damn interesting,” Stanley said to me. “It is the greatest grace that you and I could ever have known – to be born. We could be lichen growing on the north side of trees in the mountains. Goddamn, it’s wonderful. This is the day the Lord hath made, let us rejoice and be glad in it.”

THREE. I visited Stanley right before the pandemic, arriving in Memphis late one evening, in the rain. He sat in his wheelchair in front of the television, surrounded by his books and clutter, unwashed, in need of a shave. It was weeks since anyone had come to visit. Having been alone a long while, he warmed up slowly. We talked of writing, the weather, family, film, childhood and more — whatever came to mind, to keep the conversation going, to lift his spirits.

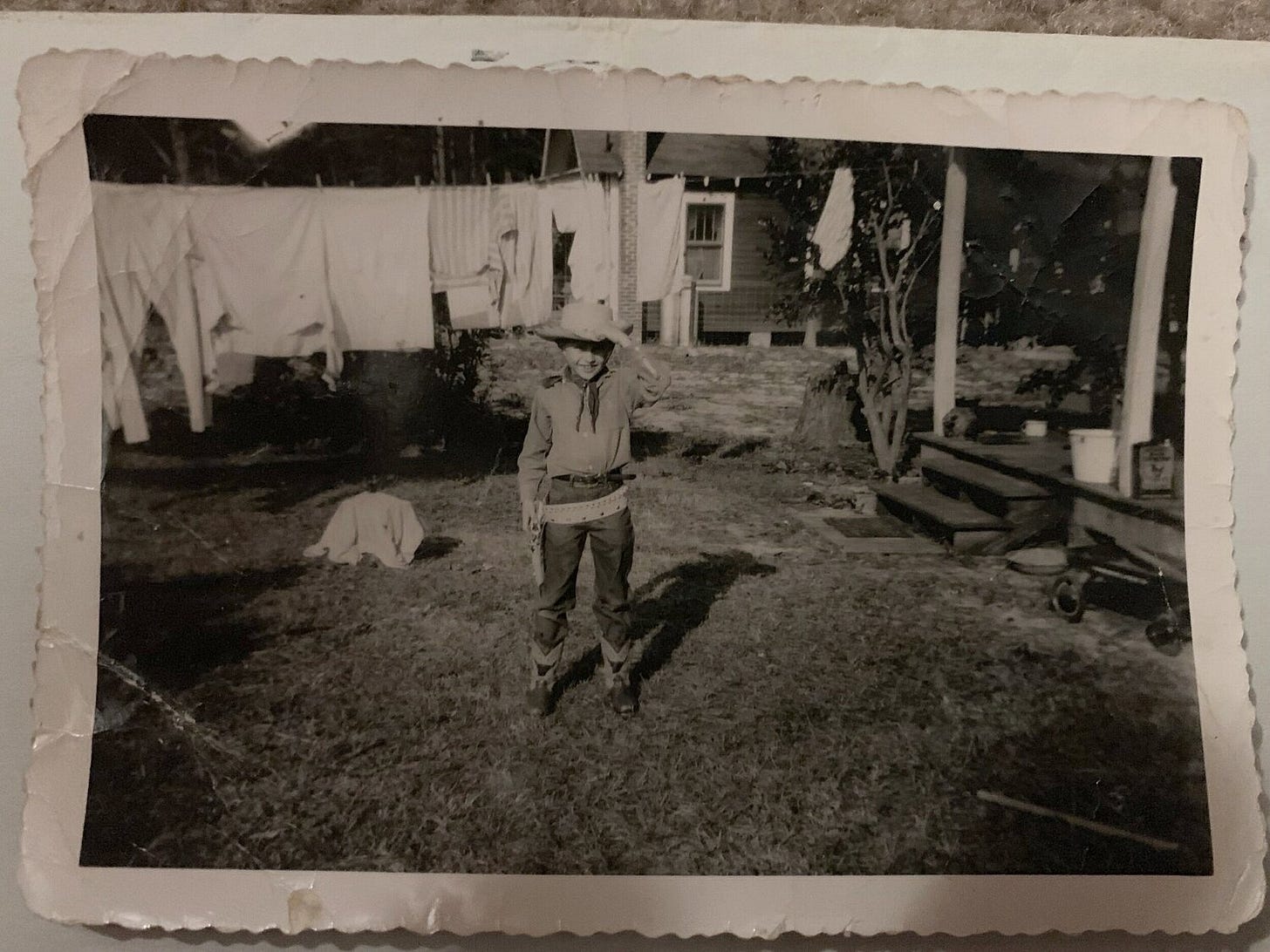

Hung in the front hallway was a picture of Stanley as a boy, dancing as Elvis in a dark suit and white shirt, collar popped, with a makeshift microphone and Shinola sideburns. Above this, a formal portrait of his mother as a young woman, with the poised, delicate face of a silent film star. For decades she taught elementary school, with the sort of patient, devoted consideration that led her to ask of all visitors, as they first entered her house, “Do you need to use the bathroom?” and who each year would tell her husband and son, with all sincerity, “I think these are the nicest boys and girls I’ve ever had.”

“I was a very happy child,” Stanley told me, “I would hear my mother laughing in the night. I’m sure my father was fucking her, you know what I mean? But he was so funny that he probably had a very amusing way of fucking, and I would hear suppressed laughter that was loud enough for me to hear, but I always felt so good because my parents were in love and I had a happy home.”

He was an only child, precocious, well-loved, encouraged in his reading. He discovered with excitement and esteem The Royal Road to Romance by Richard Halliburton, the adventurer (another Memphian) lost at sea and presumed dead in 1939: “Let those who wish have their respectability — I wanted freedom, freedom to indulge in whatever caprice struck my fancy, freedom to search in the farthermost corners of the earth for the beautiful, the joyous and the romantic.” Stanley also received a complete set of the Childcraft Encyclopedia, wherein he read Mildred Pew Meig’s poem “Pirate Don Durk of Dowdee” — “It’s true he was wicked as wicked could be, / His sins they outnumbered a hundred and three, / But oh, he was perfectly gorgeous to see…” — which allowed him, he said, to recognize Keith Richards when they finally met in London in September 1968.

“There was something about him that astonished me,” Stanley later wrote, “Keith’s intensity of focus and his obvious rejection of middle-class values almost made me speechless.” What would happen, ultimately, when that very rejection became itself a middle-class value was left for a later age to consider — instead, in the spirit of Halliburton himself, what Stanley would describe as “a battle between opposing ways of life” had already been joined, and the stakes were high. “One reason… for the emphasis rock music has received in the 1960s,” he observed in his piece on the Stones, published in Eye in two parts over the spring of 1969, “is that there is no such thing as a natural vacuum. It should come as a surprise to no one that in recent years certain occupations and institutions which for centuries had been worth living and dying for, have come to be regarded by many people, especially young ones, as no longer even worthy of being taken seriously. It is true that there are those still dedicating themselves to careers in the church, the Army, or business, but one does not think of them as being among the vanguard of the new youth.”

With the Stones and their milieu, Stanley had the satisfaction of chronicling that vanguard, those “few people who can and do live other people’s lives for them.” But while following the band on their American tour in the fall of 1969, hoping to write a book with their cooperation, he began to intuit certain strange instabilities at play, driving the whole enterprise toward ruin. “The only victory might be in simple survival,” he later wrote, describing the heady days of the tour, “Or so it might seem if Mick didn’t keep leaning out over the stage each night, singing, as if it were a Sunday School song, ‘I’m free — to do what I like, justa any old time…’ It never sounded true. If it were true, true just once… that would be a victory. As long as Mick kept saying ‘we all free,’ that was what he had to achieve. If he wouldn’t say that, if he’d settle for less, then maybe victory would be easier; maybe there was a simple and easier victory. Maybe.”

Instead, on December 6, 1969, at Dick Carter’s Altamont Speedway in northern California, the hopes of the vanguard were shattered against a hard and immutable truth counselled by Hemingway himself, that “all stories, if continued far enough, end in death.” In this instance, the murder of Meredith Hunter, aged eighteen, at the hands of the Hells Angels, at the front of the festival stage — which Stanley saw paralleled, in some darkly Providential fashion, the untimely death of his friend Brian Jones, founder of the Rolling Stones, earlier that year.

While Hunter’s murder took only seconds, and the tour itself lasted less than a month, for Stanley, left now with his notes, a nearly interminable, purgatorial aftermath was just beginning. “What you do,” he said, “is sit in front of a typewriter for fifteen years while the blood drips from your forehead.” For the length of time it took Stanley to complete The True Adventures of the Rolling Stones — published finally in 1984 as Dance With the Devil, a title forced upon him by the publisher, and renamed, correctly, in subsequent editions — drugs, mayhem, and general inattention surely played their part. But his notebooks for the period also betray an almost paralyzing fear that something essential be misperceived in any words cheaply won. “Nothing matters if I can’t write this book. Why can’t I? Because I can’t quite capture that beginning. Terribly intense period of history — exhilarating — hard to capture — hard to explain in a calmer time.” What Stanley wanted, as he had once noted of Hemingway, was “the good, clean serious feeling one had when reading the work of a man who will not lie to his reader.”

“I remember standing in a chair in my grandparent’s hall in Cogdell, Georgia,” he told me, “a little turpentine camp, talking on the phone, which was a wooden phone on the wall and you picked up the earpiece and you rang Bernice in Homerville ten miles away. ‘Bernice? This is Lester Booth over in Cogdell. Could you ring Dr. Mickey for me please?’” Stanley lived at the camp in early childhood, a brutal place, “where life went on as if Emancipation had never been proclaimed.” His paternal grandfather was foreman, charged with keeping the black workers from running off or being stolen by other camps. One morning, a worker named Frank Porter, whom Stanley remembered as “a special friend of mine… the most trusted black man in the camp,” and whom “the pressures of peonage had obviously unhinged,” tried unsuccessfully to stab Lester Booth, with Stanley, only five years old, watching. “My grandfather was carrying a pistol. Frank ran across the street, into the fog. His wife was coming across the street the other way. My grandfather shot at Frank and hit Frank’s wife — didn’t kill her. But Frank disappeared.”

“I was a little bitty thing…” Stanley recalled, “I was left to make sense of it on my own. I didn’t understand anything at that point — I mean, all I knew was that I loved the black people that lived there, I loved my parents and grandparents… and life was simply grand.”

“In fact,” he said, detailing his later attempts to write of what had happened, “I thought that my father had come out and shot and hit the woman, and my father told me, he says, ‘Well, if you want to write it like that, that’s OK, but actually your grandfather shot her.’ And I said, ‘No, I don’t want to do that, I want to write the truth — I thought you shot her.’ He said, ‘I didn’t.’ I said, ‘OK, I’ll change it.’”

Sitting there beside Stanley in his living room, I thought again of pilgrims and prophets, still wondering why I’d come to Memphis. A few months earlier a woman had reached out to Stanley on Facebook, claiming to be Keith Richards’s new girlfriend. I remembered how happy Stanley had sounded, reestablishing that connection. “She says Keith adores me, and they love my books.” The woman turned out to be a single mother, troubled and lonely, living in New Jersey, with no connection to Keith. Stanley was embarrassed by his own credulity. We talked about it only briefly.

“Keith and I, we’ve done a lot of things together,” he said, reflecting, “but what we’ve done most often, I regret to say, is watch our friends die.”

“Each man makes his own plagues,” St. Gregory of Nyssa preached. The previous summer Stanley spent several weeks in a hospital rehabilitation facility, recovering from pneumonia. His daughter visited him, briefly. What might have happened between the two to sour their relationship I never had the heart to ask — sometimes being polite is better than being thorough. It can’t have been easy, for either of them. When she was born in 1978, Stanley’s parents, desperate to protect their granddaughter, and wanting to give her the sort of life they’d given their own son, tried to buy the child for $30,000 from the mother and her new boyfriend, a baleful man who used to hunt wolves on islands in the Mississippi. He telephoned to ask Stanley’s opinion of the deal. “I think you’re a creep,” Stanley told him, “You’re trying to sell a baby. You’ll be lucky you don’t end up in prison.” The deal fell apart. Stanley’s parents were distraught. Their attorney, relieved that money was finally off the table, told them to sit tight: “They don’t want that baby.” Three weeks later the mother and her boyfriend gave the child up for free. When Mr. and Mrs. Booth moved back to Georgia, the girl went with them, and after the Stones book was published, Stanley followed. “She lived with them,” he said, “I had her on the weekends. I would go over every day and read to her. We read all of Sherlock Holmes, except that one about the snake, “The Speckled Band.” I read her Huckleberry Finn, I read her Thurber, I read her Kafka. She was in the fifth grade at St. Simon’s Elementary School… I picked her up at school, and we’re driving over to my parents’ house, she told me they were having this thing about stories. She said, ‘I started to tell them about that story you read me, about the man who turned into a bug — but then I thought maybe I better not.’”

While Stanley was in rehab a priest also visited, to anoint him and bring him the Eucharist. Stanley had no parish in Memphis. When he first returned to the city, in 2014, he intended to settle at the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, until encountering there two deacons “who were so spiritual,” he told me, archly, he got up and left. He had little interest in having a priest or a Eucharistic minister visit him at home, now that getting out of the house was too burdensome. He wanted to go to the church himself, he said — to light candles, to kneel and pray.

Chronic arthritis in Stanley’s feet made walking difficult. I helped him turn his wheelchair, guiding him back down the hallway toward the bathroom, then began clearing space on the living room floor, to make moving around a bit easier. In a box beside the chaise lounge I found a copy of a letter to Jann Wenner, publisher of Rolling Stone, dated March 1975, and typed painstakingly in the blank spaces of an official Record of Death form from the John Gaston Hospital in Memphis: “…I have in the time I’ve been honing the Rolling Stones book into the Domesday Book of our generation also been collecting stories to tell… things I can’t even mention now, such as what happened the other night when Sam Phillips got fed up trying to send telepathic messages to Gerald Ford and called Fidel Castro.” The letter, signed with the initials of the Okefenokee Kid, Stanley’s nom de plume, contained also the requisite bitching about not being paid enough, and complaints regarding persistent typographical errors in his pieces for the magazine. In the same box, a Sun Records 78, the Prisonaires’ “Just Walkin’ in the Rain” autographed by Sam Phillips himself.

“They’re real, those spirits,” Mick Jagger told Stanley, half a century ago, “and the people to come after us will know about them.” But like all phantoms, their traces are frequently elusive and unsatisfying, even obscured. Elvis, Otis, Furry, Sam Phillips, the Rolling Stones — I thought of a Creek Indian legend of the Okefenokee, where Stanley spent his boyhood, recorded by William Bartram, the eighteenth century naturalist, of an enchanted island in the labyrinthine depths of the swamp, a paradisal island whereon lived a passel of beautiful Indian maidens, daughters of the sun, who offered aid to weary travelers, but whose blessed home could only be seen from afar, and never approached. This, alongside the dispiriting realization I can never hear “(Sittin’ On) The Dock of the Bay” without also hearing in my mind its ill-considered use in a Hires Root Beer commercial from the late ‘80s: “Just sittin’ with my Hires all day / It’s got the taste for when you’re feelin’ this way…”

“Some people survived that era and some didn’t,” Stanley wrote, “…those days, when the world was younger, and meanings were, or seemed for a time to be, clearer. Almost forever ago.”

I heard Stanley cry out as he eased himself back into the wheelchair, coming out of the bathroom. He wheeled slowly down the hallway. His physical discomfort was obvious, and pressing. Because it seemed the only appropriate thing to do, I suggested I help him get into the bathtub, that a wash and a shave might make him feel better. He agreed without fanfare. He knew he needed help.

I drew a bath, helping him out of his soiled clothes. When the water was high enough, I scooped him up from the chair and settled him down into the tub. He weighed very little — it was like handling a child. I used a washcloth to wash his body, shampooed and rinsed his hair, then lathered his face with shaving cream and went to work.

Afterward I helped Stanley out of the bathtub and set him down on the toilet. While he blow-dried his hair, I dried his feet — swollen and bent from arthritis — with a towel, then sprinkled them with baby powder. I noticed a vintage Hopalong Cassidy mug on the sink beside his toothbrush. I marveled at the ivory smoothness of Stanley’s hands.

After the bath, dressed in clean clothes, he was smiling. We drank Jameson’s and watched Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood. “Quentin’s too young to make that film,” he said later. I wondered — but kept it to myself — whether that might be missing the point entirely.

When I left finally, a day or two later, I gave Stanley a rosary. My daughter had given it to me — plastic beads, with a plastic crucifix. He hung it around his neck.

“Pray for me,” I said, “Pray for my kids.”

“I pray for you every day,” he replied.

I saw behind him on the wall the portraits of Lash LaRue, his boyhood idol, hung above the chaise lounge. He became friends with Lash as an adult, and when Lash would come to Memphis Stanley would get him stoned.

“When does that ever happen?” Stanley asked, “When do you ever get to hang out with your boyhood idol and get stoned?”

“It’s a beautiful country, ” I said, and laughed.

I drove out of Memphis in the rain, heading west, past the pyramid, across the river. On the stereo James Carr sang “The Dark End of the Street,” a song Stanley calls “the national anthem,” co-written by his friend Dan Penn, and a hit for Goldwax Records in 1967: “They’re gonna find us / They’re gonna find us / They’re gonna find us, love / Someday…”

“Here you are,” Stanley once wrote, “in exile — and the only way out is to write this book, which you must do — or die. You may die if you prefer…”

And then: “It is late. All the little snakes are asleep.”

I made my way back home at last. Evening came and morning followed, as it has since creation. Spray painted down the side of a freight train, somewhere along the road, and read through tears:

I D O N ’ T B E L I E V E I N G H O S T S

I K N O W T H A T Y O U A R E G O N E

Brian Kennedy is the founder of Lydwine, as well as the frontman and principal songwriter of the arthouse country band The Cimarron Kings. He lives with his wife and six children in Guthrie, Oklahoma.

As Sylvia Plath wrote, only days before she died, “Once one has seen God, what is the remedy?”

So good I want to read it again!

The tune and lyrics made me think of this part two. Somehow, I can't quite nail it down, it captures the essence of this essay. Hope, life, laments, and yet, the night comes, we age, and the morning follows. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EPFj-8tMXdg